Is there a passenger in the car? Summary document

What can we expect from everyday car-sharing as part of the ecological transition?

Nolwen Biard, September 2023

Although cars are designed to carry 4 or 5 people, being alone in the car is a very common practice for everyday journeys, and has almost become the norm for journeys to work. It is estimated that 28% of the increase in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the transport sector, France’s biggest emitter, is due to the fall in car occupancy rates since the 1960s (Bigo, 2020). Numerous levers for public action have been developed to increase the number of people carpooling on a daily basis, and a 2023-2027 Carpooling Plan has recently earmarked unprecedented funding for this objective. This study questions the capacity of current public policies to massively increase car sharing and the relevance of this objective at a time when the unsustainability of our mobility practices and lifestyles is being increasingly highlighted. Could the car, by becoming shared, become one of the solutions to the problems it has helped to create? This study, carried out between 2022 and 2023, was based on data available on a national scale as well as case studies from various local authorities and structures. It was therefore carried out in the midst of the structuring of policies to support everyday car sharing at national level - with the publication of a Car Sharing Plan during the study - and the recent development of certain car sharing policies at local level, following the Loi d’Orientation des Mobilités (LOM) of 2019. Interviews were conducted with public and private players involved in the development of car sharing at national and local level.

To download : 2023.09.11_vf_etude_covoiturage.pdf (5 MiB)

Massifying everyday car sharing, a consensual and plural objective

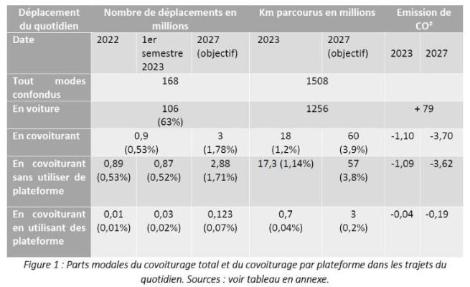

While the practice of car sharing is as old as the car itself, the expression of a quantified objective to increase car sharing is a recent development. First formulated by Elisabeth Borne, then Minister for Transport, in 2019, the objective was reaffirmed when the Carpooling 2023 - 2027 plan was revealed: the number of daily journeys estimated in the government’s communication at 900,000 was to rise to 3 million. The development of car-sharing appears to be an unquestioned fact of life and has been put on the agenda by a majority of local authorities. In some areas, local authorities, associations and companies have been experimenting for the last twenty years with all kinds of schemes to put carpoolers in touch with each other. Despite these experiments, car occupancy rates have continued to stagnate. The widespread use of car-sharing on a daily basis is on the agenda for a number of public policy objectives:

-

Ecological objectives (lever for decarbonisation of transport, reduction in air pollution) ;

-

Social objectives (accessibility to services and activities for non-motorised users, social and territorial justice, strengthening social links);

-

Optimisation of the mobility system (decongestion of road infrastructure, savings for the transport budget of the AOMs).

Despite the consensual nature of the development of policies to support car sharing, not all the associated objectives are relevant from an ecological transition perspective. Optimising the car system by reducing the cost of use or making infrastructures more fluid can reinforce the predominance of the car and compete with more efficient modes of transport to reduce the ecological impact of our mobility.

More or less intermediated, more or less financed car-sharing practices

Carpooling has many faces. It can be practised on a daily basis without the intervention of an external intermediary, within family, friendship or professional circles. The existence of an intermediary, encouraging the creation of carpooling teams, can be more or less important. It can range from the simple organisation of workshops within a company, to dynamic meetings (where people can be put in touch at the last minute) via a platform where the entire carpooling relationship is intermediated by the platform’s functions, right down to the geolocation of the driver and passenger on the journey made in order to produce « proof of carpooling ». This proof is valued by the Carpooling Proof Register (RPC) and then by the National Carpooling Observatory. It is a condition for the distribution of subsidies paid directly to carpoolers, the amount of which can exceed the simple sharing of journey costs since the LOM. It is this form of carpooling, based on a platform and measured, that is the main target of the Government’s Carpooling Plan and a growing number of local authorities. This car-sharing plan is considered to be a priority project that is monitored on a monthly basis by the Prime Minister. Its key measures include a €100 car-sharing bonus for any first-time driver who makes at least 10 journeys in three months via an intermediation platform, as well as financial assistance for local authorities to support their local car-sharing subsidy policies.

The cost per journey of these intermediation services varies widely depending on the area, the type of car-sharing service set up and the economic model supporting it, and the objectives being pursued. For example, the cost per kilometre for the Syndicat mixte des Mobilités de l’aire grenobloise (SMMAG) and the Parc industriel de la Plaine de l’Ain (PIPA) is €0.60 including operating costs, for Covoiturage Pays de la Loire €0.13 and for Rouen Métropole €0.14. The amount of subsidies per journey paid to the driver, per passenger, was particularly high during certain incentive campaigns (up to €6 for the Genevois Métropolitain Pole, €5 for Covoiturage Pays de la Loire, for example), leading local authorities to quickly review incentive levels.

The mirage of a car-sharing « boom

Since the end of 2021 and particularly since 2022, the growth rates for everyday car sharing put forward by public authorities or the media seem spectacular and are often described as a « boom ». They are based on figures from the RPC, which began recording journeys in 2020, and whose data show a 3-fold increase in the number of journeys across France between January 2022 and January 2023, and up to a 10-fold increase for some local authorities. However, this massive increase in car sharing is largely a mirage. On the one hand, carpooling via platforms is still practised on a very small scale on a daily basis: in 2022, 14,000 journeys were recorded on average, or 0.013% of daily journeys made by car. In the first quarter of 2023, the number of journeys doubled, thanks in particular to the effect of the Carpooling Plan (27,000 journeys per day on average). The importance of carpooling remains very low compared with the overall volume of journeys. In the Rouen conurbation, despite being the « leader » in platform carpooling in 2022, only 0.38% of local journeys made by car were carpooled using a digital platform 1.

The differences in performance observed between local authorities do not necessarily mean differences in the effectiveness of public policies in increasing overall car sharing, but rather differences in the level of development of platform car sharing. This can therefore just as easily mean new practices as revealing already existing and informal practices. In the first quarter of 2023, platform car sharing represented only 3% of total car sharing 2. In a number of case studies, the levels achieved by platform carpooling and carpooling assisted by policies remained well below the informal carpooling already observed upstream of these schemes 3. For example, in the Toulouse conurbation, the journeys recorded during the Commute scheme were five times lower than the level of carpooling declared by employees in the mobility surveys carried out prior to the project; the journeys recorded by Covoit’Tan represented an average of 1% of informal home-work carpooling journeys in Nantes métropole; in Rouen métropole, the levels of informal carpooling to work were five times higher than the carpooling recorded by the RPC.

Despite being in the majority, informal practices are invisible, for a number of reasons. Firstly, little is known about them, as mobility surveys do not systematically take them into account, and variations in definitions from one survey to another make comparisons difficult. Secondly, car-sharing plotted and measured daily by the RPC provides public authorities - and their constituents - with daily evidence of the effectiveness of the public policies deployed. Consequently, informal car sharing - which does not provide such evidence - suffers from less political and financial support.

Finally, Mobility Organising Authorities have relied heavily on financial incentives in the hope of attracting car-poolers to car-sharing. Public incentive policies, which are still recent, have distributed high subsidies per journey, which would be unsustainable in the long term if the objectives set were to be achieved. The daily car-sharing sector, dominated by a few car-sharing operators, is now largely dependent on public funding, on which their business model is largely based.

A lack of targeting severely limits the real impact of public car-sharing policies

On a global level, the development of car sharing has been measured - and encouraged - mainly in dense, or even very dense, areas at the heart of urban areas. This can be explained by the fact that some car-sharing schemes are characterised by a lack of prior targeting and steering. Most of the services offered by short-distance car-sharing operators have been deployed in an area with few or no specific conditions on the type of journeys made (distance, perimeter, frequency). As a result, journeys were recorded first and foremost where the critical mass was most easily achieved, in dense areas already equipped with mobility solutions or where the development of a cycling, walking or public transport network is considered relevant by the public authorities. Faced with a number of irrelevant journeys (competition with public transport or active modes) and a number of opportunistic behaviours (fraud, very short journeys) due to the presence of generous financial incentives, some AOMs have gradually introduced more restrictive subsidy arrangements to achieve the initial targets or limit windfall effects (minimum/ maximum distance, monthly earnings limit, etc.). However, national policy, particularly via the bonus for first-time drivers, confirms the lack of targeting of car-sharing policies and gives private operators considerable room for manoeuvre. For example, the SMMAG concentrates the financial incentive on zones or routes that are well defined upstream, whereas some of the journeys recorded by the RPC do not meet these criteria, but are encouraged in particular via the CEE granted to operators.

The social challenges of car sharing

Car sharing raises social issues that should not be ignored. Our collective dependence on the car restricts access to services or activities for part of the population, due to material conditions of existence (income, age, physical condition, etc.). Carpooling is already practised informally by people who do not have a car, or by people who are trying to reduce the burden of car travel on their daily lives: sharing costs (because of low income, long home-work distances or the lack of alternatives to the car to reduce costs), sharing the burden of driving, etc. Working men and women are over-represented among regular carpoolers to work. Various experiments have been developed, sometimes under the name of « solidarity carpooling », to give disadvantaged groups access to mobility. For example, the study explored carpooling initiatives at the Plaine de l’Ain industrial park to overcome the lack of accessibility to a business park disconnected from the urban fabric, and the work of the Ehop association, which helps people without cars to get in touch with volunteer drivers. The cost of such initiatives appears to be very high, as they involve significant operating costs, even if this has to be seen in the light of the social objective being pursued.

Structurally limited potential to meet the challenge of ecological transition

Although car sharing is widely practised for socio-economic reasons, it helps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by increasing the occupancy rate. In areas where car sharing is ecologically relevant (when it is practised by former car users, in areas with few or no alternatives to the car), its potential appears structurally limited. At present, despite incentive policies and a real commitment from local authorities and the State, platform car-sharing accounts for only 0.05% of the distances travelled by car for everyday journeys and 0.18% for « home-work » journeys 4. While informal carpooling, within professional, friendly or family circles, is equally well practised in dense and sparsely populated areas, dynamic and measured carpooling suffers from difficulties similar to public transport in sparsely populated areas, with a low number of common origin-destination points, leading to organisational constraints and greater uncertainty for the passenger, particularly where other alternatives do not exist or exist only to a limited extent. At a time when there are so few constraints on individual car use, convincing passengers who were previously self-propelled to accept such organisational constraints is particularly difficult, as is accepting the constraints inherent in sharing a vehicle with a stranger every day. The trend towards individualised lifestyles is also not conducive to car sharing, which still meets with strong resistance. Finally, it should be pointed out that financial incentives only change some of the decisive factors in car sharing, which does not lead to a lasting increase in car occupancy rates. What’s more, most of these incentives are currently aimed at drivers.

To date, therefore, the daily car-sharing policy of the State and the AOMs does not appear to be as ambitious a decarbonisation policy as had been hoped. Carpooling by platform and measured monthly remains extremely low in daily journeys, despite the major financial efforts made by the State and local authorities. While financial incentives have a leverage effect, as mentioned above, they also lead to windfall effects and an intermediation cost that largely contributes to financing car-sharing platforms. In terms of the decarbonisation objective, the cost to the community is high: around €750 per tonne of CO2 saved, assuming an average journey cost of €2.50 (financial incentives and platform commission) and an average distance of 20 km. The cost per tonne of CO2 saved varies widely depending on the scheme in place (up to €3,000 for some local authorities).

Car sharing is an attempt to adapt to the existing car system, but it does not challenge the fact that 80% of the kilometres travelled are by car, in vehicles that are often oversized for everyday use. The car-sharing policies developed by local authorities appear to be a public policy « for want of a better one ». They are marginally adapted to long-term trends: difficulty in covering more complex and individualised mobility needs, concentration of activities and services in metropolitan areas and longer commuting distances, administrative boundaries of the AOMs that do not correspond to the catchment areas and travel practices, etc. The longer-term challenge is indeed to question and transform mobility needs and regional planning. Car sharing must be integrated into the mobility system, in which access to activities by walking or cycling, and the development of public transport lines with regular intervals, including in sparsely populated areas, is a necessity.

-

1 In the first quarter of 2023, 3643 journeys made via digital platforms were recorded on average each day within the Rouen Metropolis. According to the 2017 EMD of the Rouen Metropolis / CA Seine et Eure, residents of the metropolis make 941,000 journeys by car every day. 0.38% of journeys made by car every day are therefore carpooled via digital platforms.

-

2 In the first half of 2023, there were 27,000 car-sharing journeys made via platforms, according to the National Car-Sharing Observatory. According to the national carpooling plan, 900,000 journeys are carpooled every day. Journeys made via platforms therefore represent 3% of carpooling journeys.

-

3 Even though mobility surveys measuring informal carpooling are sometimes ten years old.

-

4 According to the EMP 2019, an average of 1,256 million km are travelled every day by car for everyday journeys. During the week, 364 million km were travelled by car for journeys between home and work. On average, according to the National Carpooling Observatory, in the 1st half of 2023, 27,265 daily journeys were carpooled via platforms, with an average distance of 24.6km, so 0.67 million km were travelled each day on average using carpooling platforms. This represents 0.05% of the km travelled by car for local journeys and is equivalent to 0.18% of those for home-work journeys.