Car-sharing as a lever for ecological transition, if it is integrated into defined zones of relevance

Nolwen Biard, September 2023

Studying the relevance of car-sharing means questioning the very objectives of car-sharing policies, in order to determine whether they are part of the necessary ecological transition of mobility: decarbonisation of mobility, social objectives linked to accessibility to mobility, or the objectives of optimising the mobility system. To make everyday car sharing a real lever for the ecological transition, the development of this practice must be observed as a priority on journeys where its development potential is greatest, and where it is least likely to be diminished by rebound effects. To this end, the definition of carpooling relevance zones should make it possible to design the characteristics of journeys where these two conditions are most likely to be met.

To download : 2023.09.11_vf_etude_covoiturage.pdf (5 MiB)

Which journeys should be targeted to reduce CO2 emissions?

The objective of decarbonising mobility is the main objective studied in this study. Car sharing can be considered as a tool for decarbonisation provided that there is no other mode that is more environmentally friendly, can be deployed efficiently and is financially sustainable for the local authority and/or the user.

Intermediated car-sharing has the greatest potential for medium-distance commuting.

Work is a key factor in daily mobility, both for getting to work or school and for carrying out professional activities 1, which makes it a decisive lever for decarbonising mobility. Commuting, from home to work or study, is a source of critical mass: these are daily journeys, made mainly at peak times, to the same urban areas or employment zones on the outskirts. However, the lowest occupancy rate is for work-related journeys.

Carpooling is not relevant for all home-to-work journeys. Nearly 60% of people in work have home-to-work journeys of less than 9 km, according to the national mobility and lifestyles survey conducted by the Forum Vies mobiles (ENMMV). However, 36% of them use the car exclusively to get to work. Public policies aimed at decarbonisation should encourage a modal shift towards cycling, light vehicles2 or public transport for this type of journey, rather than car sharing.

On the other hand, the ENMMV also showed that 41% of working people travel more than 9 kilometres to work, requiring fast motorised vehicles. While it is clear that public policy should be geared towards bringing the places where people live and work closer together, these reorganisations of the territory and of organisations take time and are not currently in the majority. The number of home-work journeys over 20 kilometres has increased by 22% in number and 28% in distance in the space of 10 years (Orfeuil, 2022).

Journeys of more than 20 km are significant: while they involve a third of the working population, they are responsible for 60% of the kilometres travelled and 55% of the CO2 emissions emitted to get to work, i.e. 10 million tonnes of CO2 (Orfeuil, 2022). The vast majority of these journeys are made by car. It is therefore for these commuter journeys to work of a distance of more than 20 km that we find the greatest decarbonisation challenges in terms of volumes 3, but also the greatest potential for car-sharing: we showed in the previous section that the average distance for car-sharing is 20 km, and that its modal share doubles beyond 20 km.

Leisure or shopping trips, as well as more occasional trips to events or demonstrations, also represent a challenge in terms of decarbonising mobility. The proportion of these non-work-related journeys is set to increase as teleworking develops. For the time being, surveys and research, as well as most public policies and intermediated car-sharing services, have focused on commuter journeys. The relevance of carpooling on journeys not linked to work or study is more difficult to determine. They have a better occupancy rate than journeys to work. The decarbonisation potential is lower, but it seems easier to organise several people for this type of journey. We can assume that they are less subject to the complex organisational constraints of daily life in the case of one-off events, which makes the constraints of carpooling more acceptable, or that they are more often made within the household for reasons related to leisure or shopping. The challenges of decarbonisation are intertwined with those of accessibility, against a backdrop of the remoteness of services in less densely populated areas.

Car-sharing should be developed as a priority to decarbonise journeys between sparsely populated and densely populated areas.

The distances travelled, the choice of mode of transport and the impact in terms of greenhouse gas emissions are strongly determined by the type of journey made. Even more than the place of residence, it is the fact of making an interchange trip (between the centre and the suburbs, or vice versa) that is decisive (Cerema, 2022). J-P. Orfeuil (2022) has shown the differences in impact depending on the type of journey made by working people: while those living and working in the same conurbation (62%) travel 7 km to get to work and account for 36% of CO2 emissions, working people from suburban communities travelling to the reference conurbation (15% of working people) travel an average of 16 km and working people exchanging journeys between two urban areas (9% of working people) travel an average of 37 km. In total, 24% of the working population accounts for 53% of the CO2 emissions associated with commuting to work (Orfeuil, 2022). This means that commuting by people who do not work in their EPCI of residence has a greater impact on greenhouse gas emissions, as they have to travel longer distances to work, usually by car.

On the one hand, car use is explained by the distances involved, which are greater than for journeys within the same area. Modal shift from the car to active modes is therefore more complicated on this type of journey. On the other hand, modal shift to public transport is more difficult. These interchange flows are less well covered by public transport, partly because they are often between different territorial levels (metropolis and conurbation community, medium-sized town and community of communes) which may have different transport networks. In addition, these journeys are made between densely populated areas and sparsely populated areas with scattered settlements, making coverage by public transport more difficult. Metropolisation is exacerbating this phenomenon; the concentration of economic activities at the heart of metropolises is helping to create ever greater flows of people living further and further away. Out-of-town journeys are already the ones where we see the most extra-family carpooling, while intra-family carpooling is more common for journeys made within the same territory (Cerema, 2022).

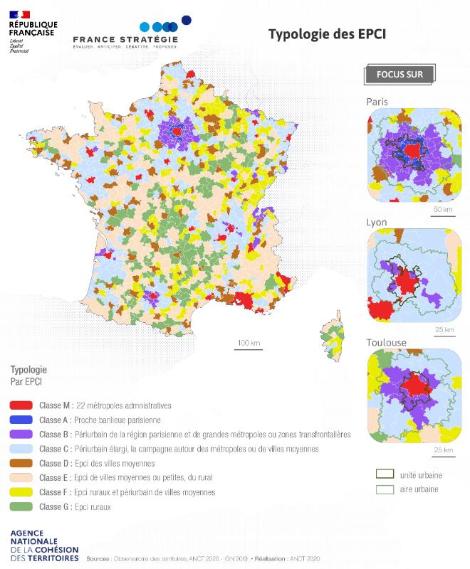

Colard et al (2021) have created a typology of EPCIs classified into 8 classes (see map below), which shows that the effects of metropolisation on mobility practices are particularly noticeable for residents of the extended suburbs (class C 4). 41% of working-class residents in class C work outside their EPCI of residence, and it is within class C that the most people travel to work by car (88% of those working in a metropolis and 95% of those working in a medium-sized town). Workers in the extended suburbs who work in metropolitan areas travel an average of 28 km, and 40% of them are employees or manual workers. The EPCIs in class C are experiencing a rapid process of land artificialisation, due to the fact that the majority of housing is detached, on larger plots of land than in conurbations, which encourages the dispersal of housing. Car-sharing is particularly relevant for this class of EPCI. It has 12.6 million inhabitants and 376 EPCIs, with a growing population that is increasingly using the car.

Interchange journeys involve suburban residents working in a conurbation, but also the reverse: residents of a dense or moderately dense conurbation going to work outside, to business parks on the outskirts, for example. A member of staff at the Pays de la Loire Region commented, based on journeys made via the regional Carpooling Pays de la Loire scheme 5: « We have a majority of journeys diverging from the metropolises (60%), i.e. going from the metropolis outwards, even though this type of journey only accounts for 40% of journeys. It’s quite interesting for us, because our public transport offer tends to converge, so it’s complementary. We also have a lot of journeys where we have very few services. For this technician from the Agence d’urbanisme de la région nantaise (AURAN), there are three possible explanations for the over-representation of journeys departing from Nantes metropole: car-sharing complements a public transport offer that is lacking for divergent journeys; parking is more limited in the heart of the urban area; the scheme was used more by young people and/or higher socio-professional categories, living more within urban centres 6.

Based on this approach, we can conclude that car sharing is most appropriate for medium-distance commuting to and from the suburbs. The decarbonisation stakes are high for these flows, and carpooling appears to be an interesting solution where the density is not high enough to develop public transport lines with sufficient intervals to provoke a significant modal shift from the car. However, it should be noted that the issue of critical mass also plays a role for car sharing, and in particular for dynamic car sharing by platform, which affects its potential.

Conversely, car sharing is not relevant for decarbonising journeys within densely populated areas, as it is possible and desirable to cover these flows by public transport, and in many cases this is already available. For journeys within less densely populated areas, car sharing can be a decarbonising tool in all cases, in the absence of other alternatives. However, the fact that flows are too widely dispersed greatly reduces the potential of car sharing.

Finally, it should be noted that the typology used gives a general idea thanks to the analysis of mobility practices and regional planning. Other territorial characteristics also influence the potential for car sharing, such as the very high density of the French road network: more than one million kilometres of roads compared with 600,000 in Germany and 400,000 in the UK and Italy. The sheer size of such a network reduces the concentration of flows and therefore the potential for pooling. On the contrary, a reduced number of lanes improves the potential, because the flows are concentrated, as for example the « Grenoble Y » corresponding to the few flows in the direction of Grenoble, in the valley.

The social challenges of car sharing in the face of our collective dependence on the car

The ecological transition in mobility cannot be limited to the technical challenges of replacing carbon-based modes of transport with low-carbon modes. It involves changes in practices, representations and lifestyles. On the one hand, therefore, it includes a cultural dimension linked to the imaginary images surrounding the use of the car. On the other hand, social justice is essential: the changes required for the ecological transition are more readily accepted when they are shared fairly by all; this is the finding of the annual survey on the perception of climate change carried out by ADEME 7. There can be no ecological transition without social justice.

The stakes of social justice are particularly high in the area of mobility, and a source of major tension, as illustrated by the recent Yellow Vests crisis. The introduction of Low Emission Zones (LEZs) in metropolitan areas is also raising a number of concerns: a Reporterre article on the subject described the LEZs as a « social bomb for working-class neighbourhoods » 8.

Making services and opportunities accessible through motoring

Mobility can be described as a « new social issue » (Orfeuil, 2010), given that the need to be mobile has become an increasingly pressing necessity. Being mobile has become a social norm, and not being mobile limits access to jobs, services, social contacts, opportunities and so on. Various factors are at the root of mobility difficulties: level of income, lack of alternatives (car dependency), physical abilities and disabilities, place of residence, etc. Social - and territorial - inequalities are reflected in difficulties of access to mobility, and are self-perpetuating ("immobility attracts immobility" according to Orfeuil) as a result of reduced access to opportunities and services. The Baromètre des mobilités du quotidien 2022, published by the Fondation pour la Nature et l’Homme (FNH), counts 13.3 million people in situations of « precarious mobility » 9, i.e. almost a quarter of the French population. The need to be mobile is even becoming a need to be a motorist, either because of the lack of alternatives to the car, or because the flexibility and availability offered by the car are becoming the norm.

The issue of accessibility is regularly raised as an objective of car-sharing policies, particularly for areas where alternatives to the private car are non-existent or not sufficiently present. Carpooling is then presented as an alternative for non-motorised users, who have no mobility solution and are faced with difficulties in accessing activities and/or services.

The typology developed by J. Colard et al (2021) highlights areas that are particularly affected by accessibility problems, due to high unemployment, an ageing population or remoteness from everyday services. These include EPCIs in medium-sized towns, small cities, the suburbs surrounding these areas, and rural areas. These different classes of EPCI (D, E, F and G) are characterised by predominant use of the car and low use of public transport. Rebound effects are limited; car-sharing does not lead to travel, as the people using these services would not have travelled if they did not exist.

These areas are characterised by a density ranging from medium (class D) to low or very low (class G), over very large areas. However, density and critical mass do not seem to be the main criteria here for judging the potential of car sharing, and are not binding obstacles 10. On the contrary, the values of mutual aid and solidarity seem essential to make car sharing work in this type of situation, which leads us to deduce that it is as close as possible to the area concerned and its inhabitants that initiatives will have the best chance of working. The promoters of this « solidarity car-sharing » scheme are therefore more interested in leadership, the local nature of the initiatives and the spirit of solidarity in the area. The existence of a human intermediary to put people in touch with each other plays an essential role, particularly for people with a digital divide, where the interface of an application alone is not enough. According to INSEE 11, this digital divide affects 17% of the population, and particularly the most vulnerable groups - who are themselves more likely to find themselves in situations of mobility insecurity.

Furthermore, it is in the least densely populated areas that the objective of accessibility can most closely overlap with that of decarbonisation: it is in these areas that residents have to travel the longest distances to access different activities or services, in the vast majority of cases by car 12.

Car sharing does not solve a number of accessibility problems, starting with the need to bring public services and activities closer together, which we will discuss in more detail in part 4. Nor can solidarity car sharing replace the existence of public transport services (such as Transport on Demand) or facilities for active modes of transport. This is because car-sharing is based on solidarity and a willingness to help, and on the availability of male and female drivers. Car-sharing cannot guarantee continuity of service. Furthermore, it should not be confused with solidarity support, which is provided by volunteer drivers who do not travel on their own behalf, but on behalf of the person being supported.

Compensating for the excessively high costs of motoring: remunerating car-sharing as an issue of social and territorial justice?

Inequalities linked to mobility are first and foremost social inequalities, because mobility is easier for people on higher incomes and with higher qualifications, and mobility maintains and reproduces these social inequalities. They are also territorial inequalities: metropolises concentrate alternative solutions to the private car (structured public transport, cycling facilities, self-service mobility services, VTCs, etc.) and they also concentrate services and activities. Residents of peri-urban and rural areas have fewer alternatives to the private car, and on average they have to travel longer distances to carry out their daily activities (work, formalities, leisure). Territorial inequalities and social inequalities are also linked and mutually reinforcing. People on higher incomes have greater control over their residential choices, and can include access to mobility services and infrastructure as criteria. On the other hand, situations of car dependency linked to the place of residence increase the burden of mobility on the most constrained budgets. The cost of owning and using a car is estimated at €350 per month in 2022 13, or around 25% of the minimum wage.

As a result, there are differences in energy vulnerability 14 between regions and between populations: in a 2015 note, INSEE counted 2.7 million households (10.2% of households) who were vulnerable in terms of their expenditure on the fuel they needed to make their journeys. The risk of vulnerability is low in urban centres, and much higher in more remote areas. This risk also varies according to socio-professional category: it is higher for farmers, manual workers and intermediate professions. The rising cost of fuel has amplified vulnerability and inequalities between populations and regions.

Carpooling support schemes can therefore be seen as a way of compensating for social and territorial inequalities arising from the distance to work, lower incomes and the lack of adequate alternatives to the car. These schemes can encourage and facilitate contacts between carpoolers, who then share the cost of the journey. The schemes can also reimburse carpoolers directly for their costs (sustainable mobility lump-sum, financial incentives distributed by the AOMs).

However, to really compensate for situations of inequality, such schemes should be able to target the groups and areas receiving this compensation much more precisely. In addition, we have our doubts about the ability of car-sharing policies to resolve a feeling of injustice linked to the lack of alternatives to the private car outside urban centres. This practice requires acceptance of a certain number of organisational constraints and a degree of uncertainty for the passenger, elements that can constitute a repeated mental burden if the search for carpooling crews is a daily occurrence. Even supposing that this burden could be considerably reduced thanks to highly efficient systems for putting people in touch with each other, carpooling means agreeing to share a small space and a journey time with one or more people, even though this time between work and home is considered by a certain number of working people as a « decompression chamber ». Carpooling will not suit everyone and cannot provide a solid response to the prevailing feeling of social and territorial injustice linked to mobility. The injunction to carpool for suburban and rural populations could even have counterproductive effects: whereas organised public transport is a public service with a strong power to develop territories, and delivers a message of « equal dignity of territories » according to J-P. Orfeuil, carpooling could « be assimilated to an invitation to ‘fend for oneself’ » (Orfeuil, 2022).

Car-sharing can create a new space for links, provided it is fully chosen

Carpooling is based on the sharing of a journey between two places, but it also implies the sharing of a journey time between several people. Yet we tend to ignore « the social depth of what happens between places. […] Mobility is not a ‘dead space-time’ between anchor points that alone would constitute territoriality. […] Our analyses of co-displacement […] reveal a specific sociability, specific to mobility, which is both a function of its temporality and of the particular space of the passenger compartment in motion. » (Cailly et al. 2014).

Strengthening social ties through car sharing is an objective stated by this elected representative of the Concarneau urban community, with the « Ehop près de chez nous » car sharing experiment: « It’s an interesting social link. In some areas, there are a lot of second homes. The few elderly people who stay there [all year round] are very happy to find people with whom they can chat and go for a drive. [Carpooling] allows you to get to know people you don’t know, even though they live in the next street, and to get back in touch with people from your local area ». In this way, carpooling can create opportunities for people from the same area or employees from the same business park to meet up. For C. Beurrier, elected member of the PMGF, « Carpooling is also about conviviality and having fun ».

The promise of a « renewed and strengthened » social bond is one of the societal hopes held out by collaborative consumption (Borel, 2015). Even though this may indeed be one of the impacts of car sharing, strengthening social ties is a diffuse objective, dependent on multiple factors. What’s more, car sharing is a very advanced form of sociability, since the limited space of a car has to be shared, particularly with strangers in the case of dynamic car sharing. This goes against current trends in travel practices. The time spent travelling on a daily basis is increasingly optimised thanks to the possibility of accessing a variety of content via smartphones and an internet connection. Car travel is valued because it is synonymous with freedom and autonomy, and offers a private, intimate space. Travelling by public transport, even if it is collective, allows people to pursue individual interests (making a phone call, working, watching a series, etc.).

So while some people may value the opportunity to meet new people and use up their daily commuting time in this way, it is not for everyone, and once again raises the question of fairness. Should this particular form of mobility be offered as the only alternative for people who have no alternative to a combustion-powered car, while others can continue to use electric cars on an individual basis? This issue arises particularly in the case of dedicated car-sharing lanes, which remain accessible to car drivers in electric vehicles.

Optimising the mobility system through the development of car-sharing?

Finally, there are two last objectives of car-sharing policies that need to be studied here: relieving congestion on the busiest roads and enabling local authorities and transport operators to offer a new service at a lower price than a traditional public transport service. Both should ultimately help to optimise the mobility system.

Reduce congestion by filling more cars on the road?

This objective is regularly mentioned by the local authorities we meet, particularly in cities facing congestion problems. Car-sharing is seen as a way of reducing the number of vehicles on the road, thereby improving traffic flow and reducing air pollution. The 2023-2027 Carpooling Plan even makes carpooling one of its main priorities: 50 million euros are earmarked for facilities (areas, lines, reserved lanes) designed to « improve traffic flow wherever possible ».

In the case of an effective car-sharing policy, which encourages car-poolers to leave their cars and become car-sharing passengers, general traffic conditions would be effectively improved by relieving congested roads. This objective responds to the practical problems faced by millions of motorists every day, and is linked to the challenge of improving accessibility. Reducing congestion through car sharing is the objective of several of the local authorities we met for this study, which are faced with continuing demographic growth. The most relevant area for car sharing, in terms of relieving congestion, is the reduction in the highest volume of journeys, whatever their distance, in dense areas affected by congestion.

This may conflict with the objective of decarbonisation. In fact, decongestion ultimately improves traffic flow for everyone - carpoolers and self-drivers alike. However, there is a risk that, in the long term, traffic fluidity will reproduce the phenomena of congestion. In fact, the temporary improvement in traffic conditions ends up, through a windfall effect, leading to an increase in overall car traffic (induced traffic), which recreates the congestion phenomena initially combated. In the example presented in the box above, the opening of an additional lane reserved for carpooling improved traffic conditions for all motorists (on the carpool lane and on the conventional lanes).

On the contrary, supporting carpooling through dedicated facilities that reduce the space given over to car-pooling - creating more congestion for car-poolers in the short term - is one way of reducing car traffic through the phenomenon of evaporated traffic.

Saving money on the transport budget?

Savings on the budget can relate to the gains in purchasing power made by carpoolers. This issue is dealt with under the objective of social and territorial justice (see above).

Potential savings may also concern the budget allocated by local authorities to transport services. The search for savings through the introduction of car-sharing services is less emphasised than other objectives, but it was nevertheless quickly mentioned in several interviews: « Car-sharing today is the public transport system that costs everyone the least. You don’t need infrastructure, you don’t need equipment, you don’t need professionals, it’s a system that has the advantage of being flexible and relatively inexpensive for the community » for this elected representative of a joint transport association. « The cost/benefit ratio is better for carpooling than for public transport », also confided a technician from a local authority during an interview. « The main problem with public transport is the cost of running it, particularly staff costs, which are too high compared with revenue, which is too low. There is also a shortage of bus drivers. The advantage of car-sharing is that you don’t have to pay a professional to drive. It’s a lower-cost solution. Even if we have to look at the bigger picture and consider the positive externalities of public transport ».

The idea of making savings by reducing the salary costs of public transport drivers is attractive to elected representatives and public transport operators: « The idea was that we were going to offer car drivers the chance to be drivers on the public transport network », recalls this agent from a metropolitan authority. We find the same reasoning behind the development of autonomous vehicles: to reduce labour costs by doing away with drivers 15.

The desire to make savings makes sense in a context where local authority budgets are caught in a financial vise: increasing expenditure combined with fewer resources. The Regions are particularly affected by this phenomenon: they devote the largest share of their budget (25.3%) to mobility, i.e. 12 billion euros, a budget that has doubled in ten years. 16

At this stage, the cost of car-sharing policies varies greatly depending on the area, the financial incentives (if any) and the type of service (ranging from an IT service to the development of infrastructure on the road). The estimated cost per km is around €0.60 (including operating costs) for the Syndicat mixte des Mobilités de l’aire grenobloise (SMMAG) or the Parc industriel de la Plaine de l’Ain (PIPA), €0.13 for the Pays de la Loire regional scheme, and €0.14 for Rouen Métropole. Depending on the business model used by car-sharing operators, this cost may remain constant, regardless of how much the service is used, or it may decrease when the number of journeys increases (to amortise the high initial operating or development costs).

In addition to the cost of the service, it is also necessary to estimate the service provided by car sharing, compared with the addition of a public transport service. This will depend on the target ridership thresholds and the quality of the existing public transport offer - or lack of it. Car sharing is a different kind of service, which does not replace public transport.

As a result, car-sharing policies may have different objectives, and not always the same goals. Improving accessibility, for example by reducing the mobility budget for households, may conflict with the objective of decarbonisation, which requires a reduction in the demand for mobility. Decongestion, for its part, may conflict with the objective of decarbonisation. The challenge for public authorities is to set in motion an ecological transition that will bring about genuine long-term change, without neglecting the social impact of their public policies.

-

1 The national mobility and lifestyles survey carried out by the Forum Vies mobiles (2020) showed that work-related journeys are poorly taken into account by mobility policies, despite the fact that 40% of people in employment travel daily or almost daily during their working hours (outside the home-workplace), covering an average distance of 100 kilometres per day. However, it can be assumed that car-sharing, particularly intermediated car-sharing, is not very suitable for these journeys made to carry out one’s professional activity.

-

2 The widespread use of light vehicles could make it possible to respond to a number of problems posed by the use of the conventional bicycle, as shown in this note from La Fabrique Ecologique and the Mobile Lives Forum: « While the conventional bicycle could make it possible to cover a distance of 9 km between 30 and 45 minutes, those who cannot use a conventional bicycle, who need to go faster, make less physical effort or have protection against bad weather can use several types of light vehicle. For example, an electric bike would enable them to cover the same distance in just under 20 minutes while maintaining active mobility; tricycles (electric or otherwise) offer greater stability; car bikes, of which there are still only a few models being prototyped, provide protection from the weather and offer a small storage space and the possibility of transporting an extra person ». (La Fabrique Ecologique, Mobile Lives Forum, February 2023: www.lafabriqueecologique.fr/pour-une-mobilite-sobre-la-revolution-des-vehicules-legers/ )

-

3 In its report on daily mobility, Cerema notes significant differences between regions in the levels of transport-related greenhouse gas emissions, differences that can be explained in particular by work-related travel: « It is the long work-related journeys that will influence the average level of emissions. Border regions with a high proportion of people working abroad and travelling long distances by car to work and back will have high emissions. Conversely, areas with a high regional employment density where working people stay in their local employment area and where there is a high use of less carbon-intensive modes of transport will have lower average emissions (Cerema, 2022).

-

4 Class C of the typology corresponds to the extended suburbs and countryside around metropolises or certain medium-sized towns (Colard, 2021).

-

5 The name of the scheme was Aleop covoiturage and was changed at the beginning of the year.

-

6 On this last point, a number of clues converge towards this hypothesis on the socio-economic profile of carpoolers using applications, although it is not possible at this stage to draw any general conclusions. Note, for example, the over-representation of executives on the Greater Lyon carpooling site (ADEME, 2017) or on the Lane carpooling line (Ecov impact study).

-

7 To the question « If major changes were necessary in our lifestyles, under what conditions would you accept them?", the most popular response is that these changes « should be shared fairly between all members of society » (64%), far ahead of the fact that these changes « should be offset by other benefits (more free time, more solidarity, etc.) (33%) (OpinionWay poll for ADEME, 2021).

-

8 Mobility insecurity is caused by factors such as « high fuel budgets, ageing cars, increasing distances to be travelled, the absence of alternative solutions to the car » or the fact of not having a car, a bicycle or a public transport season ticket, according to the Barometer. This precarious situation means that people have to give up travel for work, healthcare, leisure and other reasons.

-

9 56Final report PenD Aura, June 2022 www.auvergnerhonealpes-ee.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/mediatheque/raee/Documents/Publications/2022/Rapport-PEnD-Aura__vff.pdf

-

10 This is the hypothesis put forward in a survey carried out by the autosBus association, which carried out hitchhiking tests in the Ain and Drôme regions, measuring waiting times, the number of vehicles and the time taken to reach their destination, the density of the roads used, etc. The survey concludes that hitchhiking in the Ain and Drôme regions is a serious problem. The survey came to the conclusion that waiting times do not depend on the amount of traffic: on small roads or during off-peak hours, the goodwill of drivers compensates for their low numbers: « We think that if motorists stop very little when traffic is heavy, it’s because they think ‘someone else is going to stop’. On the other hand, this has often been confirmed on almost deserted roads when drivers have said to us ‘I didn’t want to leave you stranded’. This mechanism has been extensively studied in social psychology and is known as dilution of responsibility ». (Bus, 2019).

-

11 Insee, 2019. « Une personne sur six n’utilise pas Internet, plus d’un usager sur trois manque de compétences numériques de base », URL: www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/4241397#titre-bloc-14

-

12 The France Stratégie typology shows that it is in the least densely populated EPCIs (class F and class G) that accessibility to everyday services is the worst.

-

13 Estimate by the Climate Action Network in its report « How to transform everyday mobility », October 2022.

-

14 In this note, INSEE defines energy vulnerability as a situation in which a household has an energy effort rate ("constrained" energy expenditure as a proportion of household resources) greater than twice the median effort rate observed in mainland France in the year in question.

-

15 On this subject, see the study « The autonomous vehicle: what role in the ecological transition of mobility? » by La Fabrique Ecologique and Forum Vies Mobiles. www.lafabriqueecologique.fr/etude-le-vehicule-autonome-quel-role-dans-la-transition-mobilitaire/

-

16 These 12 billion euros exclude the expenditure of the public body Île-de-France mobilités (IDFM), which spent around 10.5 billion euros in 2022. These figures are taken from the document « Les chiffres clés des régions 2022 » (Key figures for the regions 2022) produced by the association Régions de France.