PAP 58: landscapes of marcevol fifty years of collective experience

Dimitri de Boissieu, Nicolas Antoine, Charlotte Meunier, mai 2022

Le Collectif Paysages de l’Après-Pétrole (PAP)

Anxious to ensure the energy transition and, more generally, the transition of our societies towards sustainable development, 60 planning professionals have joined together in an association to promote the central role that landscape approaches can play in regional planning policies. This article, co-written by Dimitri de Boissieu, Nicolas Antoine and Charlotte Meunier 1, retraces the beautiful adventure of the Marcevol priory, its history, the commitment of the pioneer activists, the development of a place of experiences, the struggles and commitments for the respect of the landscape. Further on, it questions the future and the central place of the landscape in the new projects to be invented.

À télécharger : article-58-collectif-pap_marcevol_vff.pdf (4,1 Mio)

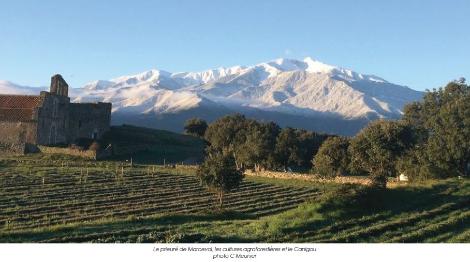

The site of Marcevol, in the Pyrenees-Orientales, has been occupied by man since the dawn of time. Situated at an altitude of 600 m on a balcony above the Têt valley, in the commune of Arboussols, its calm and singular beauty faces the summit of Mont Canigou. Set in the Mediterranean scrubland of the Conflent region, some forty kilometres from the sea, a Romanesque priory overlooks the valley. A stone’s throw upstream, a granite hamlet accompanies it. A foretaste of the mountains in Catalan country, a project area… In the early 1970s, this site was forgotten by everyone. A group of young urbanites in search of projects discovered Marcevol. Seduced by the site, they began restoring the monastery to transform it into a place of welcome. Some of them settled in the hamlet to rebuild it and live a community experience. Fifty years after the arrival of these pioneers, the landscape of this small plateau has changed. What do they perceive today of such an evolution? What links do they make between the trajectory of their collective and this landscape? On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of this refoundation, we conducted interviews with seven of the nine people who, as the core group of the project, lived in the hamlet and participated in the restoration of the priory 2.

In this text, we appropriate their analyses, expressions and points of view, while mixing them with our own as authors who are strongly involved in the site. The landscape of Marcevol will form the entrance to the narrative and the basis for the analysis of the major stages of this project.

Staggering landscape

« In the wake of May ‘68, obsessed with the idea of looking for a place of retreat, a place far from the chatter, a garden of Eden to cleanse the mind, » Xavier d’Arthuys was the first to discover the site at the end of 1971. He was captivated. What some people call the « Marcevol effect » is the shock, the intense emotion that many people feel in front of this breathtaking landscape. After this moment of amazement, the place creates an attachment from which a fertile imagination of projects develops. When you arrive at Marcevol in good weather, you are overwhelmed. « You’re stuck » by the beauty of the landscape, says Sabine Foillard. In the background, the Canigou imposes itself with its 2,784 m of altitude, strength and majesty. The symmetry of its slopes draws a landscape, the line of its ridges defines the horizon. Its wooded slopes are monumental. The view is wide, the view goes far towards the snow and the clouds. Perched at the top of the hamlet, the fortified Romanesque church of Nostra Senyora de les Grades immediately catches the eye. Built in the 11th century, it is the oldest church in the area. The imposing priory, situated below, was built a century later by the Canons of the Holy Sepulchre. To the north, the boulders of the Roc del Moro dominate the plateau and the oppidum on its summit bears witness to the oldest occupation of the site (Blaize, 1987; Garrigue, 2017). Below, the stone houses of the hamlet echo the rocky chaos. The red of their tiled roofs makes it possible to identify these small-scale constructions. When you get a little higher, the village of Arboussols appears. In the centre of the village, the bell tower of its church enters into discussion with that of the priory.

This grandiose panorama is articulated in two planes: in the distance, the immense Canigou is at a good distance. It offers the great dimension of a sublime background but remains far enough away not to produce a crushing effect. In the foreground, the gently sloping plateau offers a soothing haven from the great scale of the massif. This singular configuration defines the « spirit of the place ». In Marcevol, one feels isolated from the tumult of the world, while embracing it. Let us assume that the strength of such a landscape is the basis for the possibility of an unusual relationship, and thus contributes to the anchoring of project leaders in Marcevol. But behind this description of an idyllic place, another evocation of the site is revealed, according to the project initiators.

Hostile landscape

In their work on the community movements of the 1970s in rural areas, Danièle Léger and Bertrand Hervieu (1978, 1979) describe an intention to « return to the desert », to a space of non-civilisation, a refuge from the constraints of the dominant society or a virgin land, far from the city and its capitalist logic. Like many other places in the Pyrenees-Orientales (Bonnel & Gérard, 2016), Marcevol was chosen by a few ‘immigrants of utopia’ (Leger & Hervieu, 1978) as one of these fertile deserts. In the early 1970s, the newcomers’ awe was not only linked to the magnificence of the landscape, but also fuelled by a strong feeling of austerity. In the hamlet deserted by humans, only three families still cling to the few stones surrounded by ruins. The priory and the houses still standing are extremely precarious. The goats are the masters of the hamlet and graze everything. There are no trees, no flowers, no shady areas in the village: only stones and dust. The vegetation is overexploited, the landscape dominated by the monoculture of the vine. The wind, « which fascinates and drives people mad », blows violently and water is rare. « Everything is too much: too dry, too hot, too cold, too windy. Sabine Foillard says: « When my mother came from Paris to see me for the first time here, she started to cry because our living conditions were so harsh. What made us want to stay in Marcevol was the beauty of the Canigou, the potential of the priory, the group of friends, the common project that went with it and the desire to bring up our children in the countryside. Joanna Gasztowtt even says that in Marcevol, « the grandiose landscape makes people able to bear the harshness of the place ».

Unconscious landscape

Because of their privileged social origins and their Parisian networks, the members of the community mobilised funding and brought a patron on board. Involved from the start of the project, Pierre François bought the land and supported the collective. As early as 1972, in still very spartan conditions, the initiators of the project organised major restoration work on the priory. They founded the Association du Monastir de Marcevol (AMM). Experiencing collective life in the priory, a core group of about ten people was formed. They decided to restore some of the houses in the hamlet in order to have a community experience. The writings produced by the group at that time do not mention the landscape, nature or the territory. Their concerns lay elsewhere. The quest of three of them is to refound religious and spiritual practices. The arrival of new members and life on the spot quickly changed the objectives of the project. Living together, social, educational and cultural experimentation became the core of the project. Nevertheless, the lack of intentions concerning the landscape of Marcevol does not mean the absence of action. The restoration of the priory and the houses in the hamlet is changing the built landscape. The work is well thought out (three architects are involved) and partly supervised by the services of the historic monuments 3. Some twenty electricity poles disfigured the site. The group managed to have them removed and the lines buried in 1974. « This was a first victory, simply because it was really disgusting, » François Demptos told us. Later, an imposing concrete building was demolished, and a gas tank on the outskirts of the priory was buried. The scars in the landscape are being repaired.

Some members of the group started a vegetable garden and raised a herd of about 40 goats. They are convinced that the existing wine-growing system is out of breath and that the only alternative for this difficult hinterland is agro-sylvo-pastoral diversification. They cooperate with the breeders and farmers of Marcevol, create a cheese factory and learn the routes, trying to fence off certain plots, sow others, look for fodder outside, experiment with micro-transhumance and prune the holm oaks… « It was a challenge. We were all fired up to look for ways to make the most of this country and this not very productive land, but it was slow and difficult, » recalls Louis de Saint Vincent. These experiences « at the animals’ backsides » or in the garden allow them to invest intimately in the country, to create a strong sensitive link with nature, enriching the one developed by their numerous walks in the scrubland with the children. The investment in the landscape has taken place through concrete actions of restoration of the buildings, cleaning of the surroundings of the priory, creation of an agricultural activity and daily surveying of the territory. Without explicitly naming it, the members of the community made the landscape evolve, at a time when the notion of landscape remained the prerogative of a few painters and landscapers.

Landscape to be understood

Community life gradually came to an end in the 1980s and 1990s. Some people left for other horizons, others bought back the rehabilitated houses of the hamlet. The goat farms were moved away from the village: trees began to be planted. Grass is allowed to grow in the alleys. The priory has become more comfortable, the reception of groups is becoming more professional and has received several approvals. Heritage classes and environmental education emerged. Educational activities were developed around discovery games, landscape readings, botanical walks and stone-cutting or fresco creation workshops. In 1989, Joanna Gasztowtt welcomed a group of researchers and practitioners to Marcevol to conduct a study on the rural landscapes of the commune of Arboussols (Gasztowtt et al., 2017). The method was inspired by the book ‘Comprendre un paysage’ (Lizet & de Ravignan, 1987). A series of maps and diagrams describing the evolution of the commune’s landscapes between 1820 and 1986 is produced. In addition, Bernadette Lizet surveyed the elders of the commune and asked them about their way of life using the Macary drawings 4.

In connection with the opening of a reception and museum space at the priory, Pierre François committed himself at the end of the 1990s to enhancing this intangible heritage. The project, innovative for the time, was to create a landscape museum that would house a permanent exhibition of Macary drawings. In the end, this project did not materialise. After having experienced the landscape in a sensitive and active way, the members of the group undertook to understand it better on a scientific level in order to be able to transmit, raise awareness and educate about the landscape through appropriate didactics.

Landscape to be defended

Agricultural abandonment intensified from 1990 onwards. The cultivation of vines was no longer profitable, and premiums encouraged the grubbing up of vines. Formerly cultivated areas are becoming overgrown. Cistus, juniper and holm oak are reclaiming the area. Favoured by a sharp reduction in the size of the goat herds, the forest develops. The abandonment of the landscape to its natural dynamics then attracted the appetites of the speculators of the time. Some local elected officials were looking for new ways to develop this territory. This led to the long and tragic story of the Marcevol golf course. The idea was to create a nine-hole golf course and a restaurant. After a study phase, bulldozers were used to level the terraces, low walls and paths. An irrigation system was established using deep wells. The mixed syndicate carrying the project inaugurated the first four holes in 1997.

At the same time, the durability of the priory project was consolidated by the creation of the Fondation du prieuré de Marcevol, which was recognised as being of public interest. It was created at the end of 2001 under the leadership of Pierre François. Ownership and management of the priory are now one and the same. This initiative institutionalised the management of the priory. This heritage became a common good. The cultural, educational and environmental objectives of the priory are set in stone and better recognised, but the golf course changes the surrounding landscape. The greens are watered, carts are driven around and countless stray balls are scattered. When the water resource runs out, tankers go up to Marcevol to feed the storage basin. The golf course was closed in 2004 and put up for sale. The Corinthian Scotland Limited company then planned to build a tourist complex at Marcevol with an eighteen-hole golf course, accompanied by a huge property project (APSM, 2014). All hell broke loose! The few people from the group who remained in the hamlet created the Association de Protection du Site de Marcevol (APSM), chaired by Sophie d’Arthuys. The landscape of Marcevol, which had been damaged by the golf course, was now seriously threatened.

The APSM is mobilising the media, politicians, administrations and the general public. The defence of this landscape, its rural paths, its water resources, its small built heritage and its biodiversity is at the heart of its approach. With up to 300 members, close or distant friends of Marcevol, the association organises workcamps to clear the paths each autumn and mobilises a large public, in spring, around festive events and activities centred on the notion of landscape. In 2015, the APSM had the site recognised as a sensitive natural area. It also entered into a partnership of almost ten years with Michel Latte, who developed a remarkable work in situ in defence of the territory (Latte, 2019). The artist uses the survival blanket to magnify the place and signify its endangerment. He stages it on paths, rocks, remarkable trees, dry stone huts, humans and horses… The agricultural decline has opened the way to an artificial, disproportionate and unsuitable tourist project. To face these tensions, the group still invested in Marcevol is deploying a new militant space. The sensitivity to the landscape acquired over thirty years of life and action on the site became the core of its struggle. The adversity threatening the Marcevol site helped to reveal its qualities. The circle of his supporters widened, the collective became more active. Consciously or unconsciously, the landscape has become a major issue, a theme to be invested in to express a certain vision of the future.

Landscape to be valued

The militant actions of the APSM, the economic crisis of 2008, the vigilance of the State services and the opposition of the department of the Pyrénées- Orientales will be the reason for the golf project. The last herd of goats at Marcevol was sold in 2000, and the last vineyard was uprooted in 2007. What new trajectory should be invented for this territory? In 2006, the APSM began to think about an alternative project to the golf course. The Fondation du prieuré de Marcevol then took over. While its board of directors was initially complacent about this tourist project, the arrival of Bertrand Hervieu as president changed the situation in 2009. A sociologist, he is a friend of the group and a specialist in rural and agricultural issues. The Foundation then initiated a long process of consultation with numerous stakeholders to discuss the issues related to the Marcevol landscape 5. The project « Reconquest of the landscape and agro-ecology around the Marcevol priory » thus emerged. It will be implemented from 2016 by Dimitri de Boissieu, Joaquim Cabrol and Rosmaryn Staats on a few hectares around the priory. On a larger scale, this project is linked to the dynamics of the « Balcons du Canigó », carried out by the mixed syndicate Canigó Grand Site. Attention to the landscape is central to this experiment on dryland agriculture, which, seeking innovation, integrates productive, educational and research dimensions (Bonin et al., 2020; de Boissieu & Cabrol, 2017; Sawassi, 2018; Warter, 2018). The project takes into account the views, the orientation of the crop lines, the diversity of shapes and colours, the transparency of the fences and the impact of the infrastructures on the landscape. The alternation of aromatic plants and almond trees cultivated in agroforestry and the revival of a vegetable garden are at the heart of the system (Potier, 2017).

In the village, each household now takes care of its surroundings. The trees have grown and the flowers are blooming. « A pile of ruins has become a pretty hamlet ».

Sabine Foillard and Joanna Gasztowtt were elected to the commune of Arboussols in 2014. Alongside the mayor, Etienne Surjus, and his municipal council, they are working to protect the site in the long term by contributing to the consultation on the inter-communal local urban development plan. After the trauma linked to the golf course, the landscape has taken on its full value for the site’s stakeholders. It must be preserved, brought to life, enhanced and diversified…

Landscape to be invented

At the end of the interviews, we asked how everyone imagined the priory and its surroundings in 2072. The closure of the landscape, the difficulty of carrying out viable agriculture and the risk of fire are sources of concern. In addition, the uniqueness and landscape quality of the site is always likely to attract some financial appetite. « The rarer it is, the more coveted and therefore vulnerable it is. But the vast majority of our interviewees are confident about the future. The site has been a place of welcome and gathering since the dawn of time because « there are not many places that are so extraordinary and spacious at the same time ». The priory gives us something to think about, to connect and to move forward together. The Canigou will not move. The protection of historical monuments and the PLUi are assets. This inventive project, which is the bearer of a creative dynamic, will continue to bounce back to make this place a resource space, « as long as people know how to look, really look, and not just their mobile phones ». Collective places are developing everywhere to create links, encourage cooperation and seek a balance between human societies and ecosystems. The adventure will continue.

Mutual and perpetual enrichment

The women and men we interviewed have managed to breathe new life into a deserted place. They have lived a community experience there for fifteen years. Without any insurmountable conflicts, this initiative evolved and was able to renew itself. Each of them then went on to lead a more individual or family life. All remained in contact with each other and with the site. This adventure of life in common animated a structuring project: the priory of Marcevol, whose rescue it allowed. Faithful to its role as a place of welcome and now dedicated to meeting the challenges of the 21st century, the renewal of the priory was inspired by a radical utopia of rupture with capitalist and materialist society. Today, it continues along a more consensual path, but its function as a resource centre contributes to the invention of a society of sharing and balance with nature. There is no doubt that the continuity of the priory project and the threat of golf have nourished the link between the initial group and the site. It is also possible that the strength of the Marcevol landscape was a determining factor. It reassures, attaches and gives confidence. Its invitation to see into the distance invites one to project oneself, to invent possibilities to act in the world rather than outside it. A back and forth of mutual enrichment has been established. Fuelled and inspired by the great landscape, this project collective also nourished, protected and enriched it, knowing how to give it its current softness. Marcevol was a hard, mineral place that has become vegetated and diversified. The site has remained magical. The landscape was not the subject of the collective in 1971 but it has become so. At first it was experienced, then understood, then defended by force of circumstance, and finally considered as a central attribute of the place, to be valued. On the occasion of the project’s fiftieth anniversary, let us conclude with Xavier d’Arthuys:

« We must tell the story of the adventure that continues. I am very wary of memory, first of all because I don’t have any, especially because, as Edgar Morin said, memory should not be the memory of the past but of the future. We must anticipate what a beautiful, solid, active memory of the future should be. (…) Marcevol is neither a menhir nor a dolmen, it is a living body, it is a landscape and a landscape is something moving. I am a fan of diversity. Marcevol must always have in mind to live in diversity, in the welcome which is diversity, in the landscape which is diversity, in the diversity of ways of seeing these places (…) As Maurizio Bettini (2017) says, we must absolutely not think of things, men, women, children and places as roots. You have to think of them as a river, he says. For me, this is something essential and beautiful. Of course roots are fundamental but by definition they are planted, fixed. The river is much more important because the river carries and meanders, it diverts and is diverted. This notion of flowing and then one day drying up, another day flooding, or even overflowing, a tidal wave, must be taken into account ».

-

1 Dimitri de Boissieu is director of the Foundation of the Marcevol Priory, a resident of Marcevol and administrator of the Association for the Protection of the Site of Marcevol (APSM). Nicolas Antoine, urban and landscape planner, is a member of the APSM. Charlotte Meunier, an environmental consultant, is a resident of Marcevol and a member of the APSM.

-

2 Semi-structured interviews were conducted with Xavier d’Arthuys, Patrick de Boissieu, François Demptos, Sabine Foillard, Joanna Gasztowtt, Isabelle Mariojouls and Louis de Saint Vincent. Sophie d’Arthuys and Jérôme Gasztowtt would certainly have contributed to this collection of information if they were still alive.

-

3 The hamlet church is listed and the priory church is classified (Mérimée list of 1840).

-

4 See attached PDF drawing

-

5 The APSM, researchers, farmers, landscape gardeners, the SAFER, the Chamber of Agriculture, the department, the Foncière Terre de liens, the Grands sites de France, the Fondation de France, AGROOF, Floraluna, the Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Paysage de Versailles, the Institut Agronomique Méditerranéen de Montpellier…

Références

En savoir plus

-

APSM (2014) – Repères février 2014, 3 p. BETTINI, M. (2017) – Contre les racines. Ed. Flammarion, 192 p.

-

BLAIZE, Y. (1987) – Marcevol : un site occupé dès les temps préhistoriques. In « De Marcevol à Vinça », D’Ille et d’ailleurs, n°8 : 9-11.

-

BONIN, S., G. DES DESERTS, H. BOUREAU & D. DE BOISSIEU (2020) – Des paysages au service de la formation à la transition agro-écologique. Les séminaires agropaysage de Villarceaux et de Marcevol. Signé PAP n°41, 8 p.

-

BONNEL, J-P., & P. GERARD (2016) – Les communautés libertaires agricoles et artistiques en pays catalan 1970-2000. Ed. Trabucaire, 179 p.

-

DE BOISSIEU, D. & J. CABROL (2017) – Un projet d’agroécologie à Marcevol. In « Le Conflent, terre fertile en Pyrénées catalanes », Fruits oubliés (hors série n°1) : 23.

-

DUFOUR, S. (2021) – L’évolution des paysages autour du prieuré de Marcevol depuis le XIIème siècle. Master M1 parcours Dynamiques des environnements et des milieux de montagne, Université de Toulouse, Fondation du prieuré de Marcevol, 83 p.

-

FRUITS OUBLIES (2017) – Arboussols, avec tant de traits d’activité. In « Le Conflent, terre fertile en Pyrénées catalanes », Fruits oubliés (hors série n°1) : 30-31.

-

GARRIGUE, J-P. (2017) – Arboussols et Marcevol. Deux villages, une histoire… Ed. Les presses littéraires, 238 p.

-

GASZTOWTT, J., B. LIZET, J. RAMADE, M. BARACETTI & F. DE RAVIGNAN (2017) - Les paysages ruraux de la commune d’Arboussols. In « Le Conflent, terre fertile en Pyrénées catalanes », Fruits oubliés (hors série n°1) : 13-16.

-

LATTE, M. (2019) – Art et paysage en survie, Pyrénées Orientales, 203 p.

-

LEGER, D. & B. HERVIEU (1978) – Les immigrés de l’utopie. In « Avec nos sabots. La campagne rêvée et convoitée », Autrement n°14-78 : 48-70.

-

LEGER, D. & B. HERVIEU (1979) – Le retour à la nature, « Au fond de la forêt… l’Etat ». Ed. du Seuil, 235 p.

-

LIZET, B. & F. DE RAVIGNAN (1987) – Comprendre un paysage : guide pratique de recherche. INRA, 147 p.

-

POTIER, A. (2017) – Fondation du prieuré de Marcevol. In « A la conquête des plantes à parfum, aromatiques et médicinales du Roussillon », Ed. Trabucaire : 96-99.

-

SAWASSI, T. (2018) – Analyse des perceptions paysagères du projet agroécologique de Marcevol. Master 2 Economie et management publics. Institut agronomique méditerranéen de Montpellier, Université de Montpellier, Fondation du prieuré de Marcevol, 87 p.

-

WARTER, A. (2018) – Proposition de sentier paysager autour du prieuré de Marcevol. Fondation du prieuré de Marcevol, Agro Campus Ouest, 30 p.