Local innovations to finance cities and regions

2014

Fonds mondial pour le développement des villes (FMDV)

European Local Governments Today: increased powers with reduced resources

In 2014, 72% of Europeans are living in an urban environment characterised by polycentric urban structures and numerous intermediary cities. Despite a recent slowdown, European local governments are still responsible for more than 65% of public investment in Europe and in this respect are one of the major driving forces of European economies. Besides producing “growth” and innovation (67% of European GDP is generated in metropolitan regions), European metropolises are also the areas which concentrate the greatest inequalities and highest unemployment rates, with the corollary effects of increased social exclusion and poverty 1. In addition to the budgetary impact of the economic and financial crisis, there is the growing burden of the cost of social services 2, and the cost of current and planned long-term investment requirements for renewing infrastructure and equipment 3, and also transfers of jurisdiction from the central government. Together, these factors have led to an increase in local expenditures at a time when resources are becoming drastically scarcer. How much room for manoeuvre do European local authorities have for sustainably mobilising new resources? Which previous experiences could inspire them? What new ways of thinking are emerging from these innovative funding mechanisms?

To download : innover_localement_pour_financer_les_territoires12.pdf (1.5 MiB), local_innovations_to_finance_cities_and_regions8.pdf (1.5 MiB)

LOCAL EUROPEAN DYNAMICS: QUESTIONING THE OBVIOUS FACTS, AND MAKING A DIFFERENCE

European local public action finds itself caught in a stranglehold by the paradox between increased responsibilities and duties, active globalisation, relatively limited financial autonomy, and uncertainty concerning available and mobilisable capacities and resources. All this in a context that requires commitment to a low-carbon and redistributive society as well as assurance that the area is “attractive and competitive”. Local public action must face not only a downward trend in financial transfers from the central governments, a public-spending austerity policy based on sometimes controversial resource rationalisation strategies, and decentralisation processes of variable scope, but it also has to cope with a level of fiscal flexibility that is limited (depending on the governmental level) or highly exposed to the fluctuations in the economy. It also has to deal with unequal access to European structural funds and programmes, bank loans, and the markets for its long-term projects. European cities and regions are nodal points of globalisation flows and are organised in clusters and networks; they seek to have an influence, and to make sure the voice of subnational governments is taken into account in the drawing up, revision, and implementation of European policies. They are now better taken into consideration by the European Union, which intends to adopt a European Urban Agenda, and by the OECD, which recognised for the first time in 2014 the major role they play by validating a recommendation on the effectiveness of public investment between levels of government 4. Largely dependent on central governments’ desire to pass on the burden of the debt to subnational entities, this new situation is nevertheless an opportunity to be seized. It is a chance to rethink the European Union project by and for local authorities, at the political, economic, social and cultural levels, by offering them control and autonomy vis-à-vis the economic and financial affairs in their regions according to their mandates. capacity of European institutional stakeholders to organise multi-level regional governance and government, reconnected to local realities, to the challenges posed and to the new ways of working together likely to emerge. In this perspective, local economic development and the diversity of sources and forms of funding for urban development are the basis of the feasibility, viability and efficiency of their proposals. But which funding strategies and instruments should be put in place or adapted to favour local dynamism, as well as the financing of key sector-specific policies and a fair equalisation of resources among different areas? What optimisation of and trade-offs in spending should be proposed without going against real investment needs? Which accounting frameworks and revised indicators should be used? Who are the stakeholders in the funding of local authorities, and what are the main evolutions in the ways that traditional financial backers operate? What new institutions and relationships between European urban development partners should be implemented? Which regulatory developments should be encouraged? Which local capacities should be reinforced, and how? What is required for the transition between different local development funding models, whose impact is highly dependent on the institutional, economic and societal contexts in which they emerge and are set up, together with the capabilities of local stakeholders? To answer those questions through action, the European version of the worldwide REsolutions To Fund Cities campaign has undertaken to reveal the local European experiences and initiatives likely to inspire local stakeholders, particularly local authorities, right now. Because solutions do exist: this publication presents a non-exhaustive but representative set of policies, strategies, mechanisms and instruments activated to finance European urban development.

LOCAL EUROPEAN FUNDING AT A CROSSROADS

European subnational governments are among the major long-term investors in Europe, and they are the main stakeholders in the transition of our systems. Yet, they are suffering from a growing lack of cash resources. To make up for temporary liquidity gaps (e.g., a 30% reduction in financial transfers from the Spanish central government to local governments in 2011 5, or record interest rates in Spain, Greece and Portugal), and to adapt to the structural issues inherent in our societies (in particular, reduction of the carbon footprint, ageing populations, and infrastructure needs), emergency measures were taken by certain European States to facilitate the funding of local authorities through the support of public national institutions 6. But these measures are not a long-term response to local governments’ funding requirements. Consequently, new strategies for diversifying the funding of subnational governments are emerging in Europe, with an evolution of funding models towards the mobilisation of private capital and increased recourse to international, regional and national public financial institutions, together with the bond market. Examples include the intention to create Local Government Funding Agencies, and the issuing of socially responsible and mutualised bonds. In its new 2014-2020 budgetary framework, the European Commission intends to consolidate this trend by making available financial engineering tools with a leverage effect: Financial Instruments (FIs). Proposed by the European Investment Bank (EIB), these FIs are intended to mobilise private capital, to avoid drawing on the resources of the cohesion policy 7, to support the low-carbon economy, especially through the development of public-private partnerships such as the London Green Fund, endowed with €125 million and intended to finance the city’s sustainable development policy. In addition to these traditional forms of financial engineering, there are complementary strategies and tools that open new resource-diversification perspectives for European local governments. There are numerous trends today that contribute to proposing a renewal of urban development: emerging forms of post-network urban planning 8, concepts such as the productive city or urban farming 9, and the appearance of initiatives stemming from the share economy 10. These developments are still in their infancy, and echo each other. They are part of the considerations on the definition and role of public service, on common goods and the right to the city. They reflect on new types of contractual or partnership arrangements between “city stakeholders” and, in a globalised world, on local areas’ capacity for greater resilience via “connected” re-localisation of exchange, economic activity and production. These reflections have led to experimental initiatives that have developed into practices. For example, among the case studies presented in our work, the growing interest in the Community Land Trust 11, or the development of complementary local currencies. These practices promote values linked to use instead of ownership, and encourage a rethinking of local financial economic action, as well as local governance.

DIVERSITY AND COMPLEMENTARITY: KEYWORDS FOR EUROPEAN LOCAL FUNDING

In order to cover a broad range of proposed funding strategies and tools available to European local governments, this publication focuses on three areas of research:

-

the mobilisation of “traditional” financial resources (Chapter 1),

-

the optimisation of public resource management (Chapter 2),

-

the exploration of local and alternative funding solutions that put the local economy at the heart of the local development process (Chapter 3).

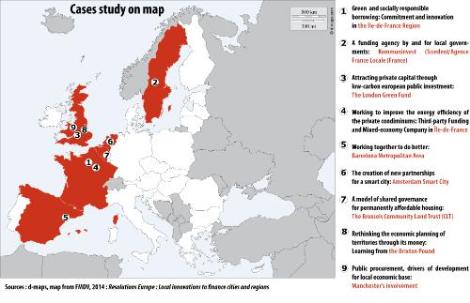

The first chapter presents three strategies that re-imagine “traditional” funding solutions through a diversification of borrowing mechanisms:

-

two kinds of bond issues –“eco-socio- responsible” in the Île de-France Region, France, and mutualised via the Kommuninvest local government funding agency in Sweden;

-

a new kind of leverage-based financial engineering through the mobilisation of European financial instruments in London. The second chapter explores policies for optimising and rethinking the management of local resources and investments.

It analyses:

-

the systems of equalisation and vertical and horizontal cooperation generated by setting up the Metropolitan Area in Barcelona,

-

the (energy) cost reductions favoured by the mechanism of third-party funding applied to energy-efficiency upgrading by the mixed-economy company Energies Posit’if in the Île-de- France Region,

-

the use of intelligent technologies by the city of Amsterdam to improve the efficiency, quality and impact of urban services.

Finally, the last chapter seeks to demonstrate that local economic development is an essential – or even priority – lever for funding urban development. For some years, European regions and municipalities have been fertile ground for innovative initiatives. They have questioned the notion of ownership, exploring various forms of high addedvalue governance, and reducing the costs of public stakeholder intervention. They have also reinforced the resilience of local economies, through the creation of sustainable local jobs and the solidarity-based and productive networking of economic stakeholders and local citizens.

For example:

-

the Community Land Trust of the Brussels-Capital Region,

-

the complementary local currencies of Brixton in Greater London,

-

the public procurement strategy in Manchester. From the words of the elected officials and their teams, each case study endeavours to analyse the principal endogenous and exogenous funding mechanisms and tools developed and/or advocated by local authorities in Europe, and the conditions for replicating them. The required regulatory and partnership conditions are also covered, along with the issue of assessing the impact of local economic development support strategies. Interconnected with each other, the examples presented form a coherent whole, which could not alone respond to future challenges. For even if there are many local initiatives, which indicate possible avenues for revitalising practices and the positive outcomes they provide, there are still no global policies that reconcile globalisation, sustainability and local realties. Our objective is therefore, through local activity, to reveal the complexity of the targeted objectives, and to present the value chains that lead to truly integrated funding and development of local projects. In that way, we propose to highlight the processes and steps required for a conscious transformation of models and practices.

AVENUES FOR THE FUTURE AND LESSONS LEARNED

In addition to financial transfers from the State, sources of funding for subnational governments may combine the mobilisation of European structural and investment funds, the diversification of sources and forms of borrowing, a modified tax system, policies for streamlining and optimising public expenses, and the mobilisation of local savings to finance local projects. In Europe, it is also essential to organise action and cooperation between the major European public banks, and also between local, national and regional banks. More reactive than national governments, local governments have the capacity to implement innovative financial initiatives that contribute to changing the mindset of bankers, national and European policies, and even the international financial system (cf. the regions’ stand against tax havens, which helped change the law in France and Europe). Local governments, in their diversity, are in a position to contribute to reducing the debt of central governments (increased solvency due to the Local Government Funding Agencies) and ensuring the funding of the energy transition (public-private company Energies Posit’if). They can also provide the levers required to support the real economy, the only true producer of sustainable prosperity. In a changing Europe, the economic and environmental sustainability of the provision of public services based on traditional infrastructure networks remains uncertain 12. Their overall costs can only increase, in particular because of the dependency of our systems on energy, food staples and raw materials. It has therefore become necessary to consider alternative forms of urban development in the light of comparative investment costs, and using indicators corresponding to the reality of available and mobilisable resources (natural, economic and financial). Beyond the simple notion of cost, it is also therefore a question of models and visions for the future. The way the funding of local authorities is considered and carried out is merely a translation of these models. For example, it is not “simply” a matter of funding an urban project produced locally, but also of using and reusing local resources, and moving from a linear model to a circular model, while continuing to develop multi-functional infrastructures, insofar as possible. Regions and municipalities are places for experimentation with interconnected initiatives that are capable of working towards several – for there cannot only be one – complementary, viable and desirable models of society. From the reappropriation of the city by its inhabitants and the groups of stakeholders who interact on and with the area, new approaches emerge for sharing responsibilities, government and governance that should be coherently promoted and developed. We see then that more than simply enabling these initiatives to exist, the role of the cities of tomorrow is to ensure their interconnectedness, in keeping with a shared and common capacity-building vision of local development. We also see that the success of funding strategies depends on numerous factors such as pro-active local policies combined with strong political backing and reinforced cooperation between the various stakeholders involved in the transition (local associations, NGOs, networks, private sector, etc.) and between governmental levels. Other ways of enhancing the value of local resources and achieving their enlightened “monetisation” include identifying the positive outcomes of a project, quantifying them, and determining the level of complementary public aid required. European local governments are taking action, and this publication demonstrates their efforts. Spread the word, experience and knowledge!

1 « La dimension régionale et urbaine de la crise –huitième rapport d’étape sur la cohésion sociale, économique et territoriale » – rapport de la Commission (Juin 2013)

2 Ces coûts se traduisent par une augmentation de respectivement 10% et 24.5 % des budgets sociaux des collectivités locales danoises et slovaques en 2010 (Local governments in critical times: Policies for Crisis, Recovery and a Sustainable Future – Council of Europe text edited by Kenneth Davey, 2011, p78- 92)

3 Il est estimé un besoin d’investissement de l’ordre de 650 milliards € par an - cf. G. Inderst, Private Infrastructure Finance and Investment in Europe, EIB Working Papers, (Février 2013)

4 http://bit.ly/FMDVReso-governance

5 DEXIA-CCRE report on European local authority budgets (summer 2012) bit.ly/FMDVReso-Dexia

6 Ibid.

7 Le financement au titre de la politique de cohésion représente plus de la moitié des investissements publics en 2011 dans de nombreuses régions « moins développées » en Europe, préserver ces ressources constitue donc une priorité.

8 L’ère post-carbone invite à transformer en profondeur tous les modes d’organisation des réseaux traditionnels vers plus de décentralisation. Vers l’essor des villes « post-réseau » : infrastructures, innovation sociotechnique et transition urbaine en Europe – Oliver Coutard et Jonathan Rutherford – LATTS - 2013

9 La ville devient ainsi un nouveau territoire agricole, envisagée pour ses capacités productives

10 Selon le magazine Forbes, la « sharing economy » pèserait ainsi 3,5 milliards de dollars en 2013, en progression de 25 %.

11 Dispositif de gouvernance tripartite et d’immobilisation des investissements dans la pierre, via la dissociation de la propriété foncière du sol et du bâti.

12 Op. cit. Coutard et Rutherford

Sources

1 The urban and regional dimension of the crisis - Eighth progress report on economic, social and territorial cohesion, Report from the Commission (June 2013)

2 These costs resulted in respective increases of 10% and 24.5% in the social budgets of Danish and Slovakian local authorities in 2010 (Local governments in critical times: Policies for Crisis, Recovery and a Sustainable Future – Council of Europe text edited by Kenneth Davey, 2011? p78- 92)

3 The investment needs are estimated to be about €650 billion per year - cf. G. Inderst, Private Infrastructure Finance and Investment in Europe, EIB Working Papers (February 2013)

5 DEXIA-CCRE report on European local authority budgets (summer 2012)

6 Ibid.

7 In 2011, funding for the cohesion policy represented more than half of public investment in many of the “less developed” European regions.

8 The post-carbon era is an opportunity to profoundly transform the way traditional networks are organised, moving towards greater decentralisation. Article in French: “Vers l’essor des villes « post-réseau”: infrastructures, innovation sociotechnique et transition urbaine en Europe” (The expansion of ‘post-network’ cities: socio-technological infrastructure and urban transition in Europe), – Oliver Coutard and Jonathan Rutherford – LATTS – 2013.9.

9 The city becomes a new agricultural area, envisaged in terms of its production capacities.

10 According to Forbes magazine, the share economy was worth $3.5 billion in 2013, a rise of 25%. bit.ly/FMDVReso-Forbes

11 A system of tripartite governance and placement of investments in bricks and mortar, based on the separation of land ownership and building ownership

12 op. cit. Coutard and Rutherford

4 analysis

- Rethinking Borrowing and Promoting Leverage of European Funds

- Reducing Costs and Investing for Tomorrow: strategies and operational solutions for optimising public resources management

- What solutions can help bring back the creation of wealth to local communities?

- Low-tech, innovations for the resilience of territories

11 case studies

- Green and Socially Responsible Borrowing: commitment and innovation in the Île-de-France Region

- A Funding Agency BY and FOR Local Governments: Kommuninvest (Sweden)

- London Green Fund: attracting private capital through low-carbon European public investment

- Third-party Funding and Mixed-economy Company: working to improve the energy efficiency of the private condominiums

- Barcelona Metropolitan Area: Working Together to Do Better

- Amsterdam Smart City: the creation of new partnerships for a smart city

- The Brussels Community Land Trust: A model of shared governance for permanently affordable housing

- Complementary Local Currencies and TransitionTowns : LEARNING FROM BRIXTON

- Public procurement, Drivers of Development for the Local Economic Base in Manchester

- Porto (PT) - Strenghtening the innovation ecosystem

- Kristiansand (NO) - From oil economy to digital hub