Mobilization of civil society organizations against the reconstruction of a road within a historical district

The case of the Matache Neighbourhood in Bucharest

Irina Zamfirescu, 2016

General data:

Bucharest: capital of Romania, administrative centre.

Inhabitants: 1,883,435 (according to 2011 census)

Administration: 6 different districts (for each of the districts there is a local City Hall; there is also a General City Hall, with responsibility for the major infrastructure projects and with the biggest local budget in Romania).

The Matache neighbourhood case:

-

A historical part of the town (with buildings dating back to the 1880’s)

-

During the communist period it was mainly inhabited by workers in the National Railway Company and middle class craftsmen;

-

Even though there is no official data on socio-professional profiles, the General City Hall stated that the area is mainly inhabited by people with “no income” and “who develop illegal activities” 1 .

The project’s history – its birth and implementation

The construction of the ‘North-South middle line’ , a road to cross the heart of Bucharest, is a project that dates back to the 1930s. It was first designed when the city had a relatively small number of cars and a large part of the buildings existing now had not yet been constructed. The first part of the project was implemented in Buzești-Berzei, an old area of the city. In the neighbourhood called ‘Matache’ the physical demolitions carried out as part of the first phase of the project have also demolished the area’s social fabric.

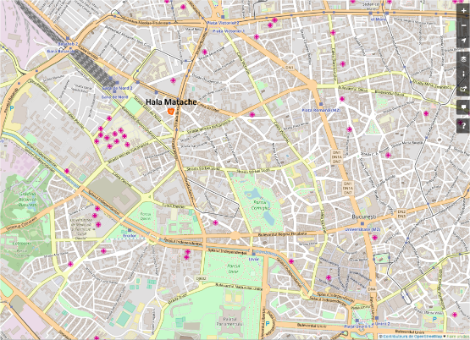

The Matache neighbourhood is situated in the northern part of the town, and has a relatively big Roma community. The area was highly stigmatized because of its community, with a high rate of people depending on social welfare and with old buildings in a rather poor state. The street is important because it connects two of the main administrative buildings: the Government and the Parliament. 98 buildings without the proper legal documents were demolished during the project; some were of great historical significance. The project was highly criticized by civil society organizations, mainly because of its lack of a social and economic dimension and its gentrifying effects. Although the project led to the transformation of the area’s social fabric3 , the City Hall considered it only as a street-widening project. The total cost of the project was estimated by the mayor at € 29.44 million for the 2 km of street that was redesigned.

The project was adopted by the District Council in 2006, without any public debate. In the same year the project was decided upon as a public interest project, therefore allowing the General City Hall of Bucharest4 to go on with expropriations. In the first years, only a few expropriations took place based on direct negotiations with the landlords in the area.

Human rights issues raised by the project

In 2010 the General City Hall obtained the right to expropriate real property without any consideration of the landlords’ rights. This led to the evacuation of 83 buildings and to the forced eviction of approximately 1000 people, in December 2010. According to Romanian legislation5 , public institutions are not allowed to evacuate people at this period of the year except in cases of extreme emergency. Human rights advocacy organizations accused local authorities of evacuating the people without considering these legal aspects.

Furthermore, among the evacuated people (former owners of the buildings), those suffering from serious social problems (ethnic minorities and elderly people) were forced to accept the compensation offered by the General City Hall. The main reason they did not contest the amount was the legislation that did not protect them. If they were to contest the amount, they would have had their accounts blocked. Being evacuated in the middle of the winter, they were forced to use the money to find shelter.

On the other hand, some of the people evacuated were tenants paying their rental fees directly to the General City Hall. They were given social housing only with a relatively long delay (approximately one year after the eviction) and in the poorest outskirts of the city.

In 2013, the public interest status of the project (which had been referred to as the basis for the forced evictions) was overridden by a court ruling. Therefore, all evictions and forced expropriations became illegal. Despite this, there were no compensation measures for the people affected.

Urbanists contesting the project

The urban project’s main aim was to widen the street in order to facilitate car traffic, so the project was designed and implemented by the Infrastructure Department of the General City Hall, without taking into consideration the particular social, economic and historical features of the area. Therefore, the project was not presented to the public as an urban renewal project, but merely as an infrastructure development scheme. Despite this, the mayor repeatedly stated that the area needed to be ‘cleaned’ and to be brought to higher standards.

Experts declared the project approach to be outdated. Widening the streets is no longer an adequate solution for problems of traffic congestion. Instead, public transportation needs to be reinforced and alternative means of transportation should be promoted. Bucharest has serious mobility problems; it is, in fact, one of the most polluted capitals in Europe. Therefore, according to the experts, the problem to be addressed is not the facilitation of car traffic, but the overall problem of mobility within the centre of Bucharest.

The lack of consideration of the overall social and economic impact was also highly criticized by civil society organisations. Anthropologists and sociologists argued that the urban fabric of the area affected by the project has developed from east to west, while the new road would increase traffic from north to south. The consequence of this project is to cut the area and segregate the local community, mainly because of two factors – creating a big empty space (the street structure) in the middle of the neighbourhood and creating a continuous flux of cars that will drive a wedge between the two sides of the street. Therefore, instead of being a development scheme on the human scale, the project fails to take into consideration the impact on local communities.

Community involvement

The urban intervention within the Matache neighbourhood was one of the most criticized projects in Bucharest. The General City Hall did not propose any public debates and consultation with its citizens on the matter, trying to frame the project as strictly an intervention on the street structure. There have been protests in front of the General City Hall, Ministry of Development, Ministry for Culture and on the site (at least 15 protests).

The symbol of this dispute between public authorities and civil society organisations was Matache Market House - a 100 year-old building. According to the original plans of the construction of the road, this building had to be demolished. However, it was protected by the law6 , and served as an important social centre of the area – including commercial space and serving as an informal civic centre.

Because of the pressure of civil society organisations (mainly through legal action), the project was suspended in 2012. With the support of the Ministry of Development, civil society (urbanists, architects, anthropologists, sociologists) and representatives of the General City Hall started to work together in order to find a solution. An architect launched a movement called ‘Volunteer Architects’. The aim of this group was to work on alternative solutions in order to prevent the demolition of the historical building. After a few months, the General City Hall agreed to a solution that the group offered: a covered sidewalk through the building. The project took note of the extended area and proposed a wider urban development plan, which was to take into consideration the Central Train Station and to connect to historical areas. Bearing in mind that the area has serious social problems and that it is the historical part of the town, it would have been an ideal candidate for an integrated urban project. Ignoring this aspect, the General City Hall agreed only with the proposal of the covered sidewalk.

(observatorul urban Bucuresti)

Because of the suspension of constructions, citizens who were still living in the area had to deal with great discomfort in their everyday life. Small local businesses (such as tailors’ establishments, restaurants, repair shops) had to close down because of the lack of pedestrians on the site. The mayor of the city publicly claimed that NGO protests were the only reason for suspending the work. Cars that normally used Buzesti Street overcrowded a nearby central boulevard. Therefore a relatively large part of the community was in favour of the continuation of the project, no matter what its final form would be. Yet Matache Market House, because of its evacuation, became the target of scrap metal thieves. Therefore it was in a rather advanced state of decay and was considered by the majority of citizens as worth demolishing. In March 2013, during the night, the building was demolished.

The Matache neighbourhood today

At the beginning of 2014 the street was officially opened to the public. This was promoted as one of the most important projects of the mayor actually in office. Up until now, no public data has been made available on the impact of the project on the area – or on the city as a whole.

The local community is still suffering from the effects of the prolonged construction work: most of the local shops are still closed. There are relatively large areas used as improvised parking lots. These are the consequences of demolishing without a thorough analysis of the amount of space the road would in fact require. Public opinion suspects that these empty spots will eventually be sold to real estate investors. The northern part of the road became highly dense with office buildings (the buildings date to not long before the beginning of the infrastructure project). Therefore it is expected that the rest of the road will develop in a similar way. This would lead to a strong change in the social fabric of the area. Poor local communities will find it very difficult to keep up with the higher living standards in the area.

Civil society still considers that the rebuilding of the Matache Market House would bring back part of the local characteristics. A project notice drawn up by The Ministry of Culture7 , although still contested in court, stipulates that the General City Hall should rebuild the historical building. The General City Hall promised to do this 36 meters away from the original site. At the beginning of January 2015, a debate was launched between the General City Hall and the City Hall of District 1 concerning the site of the future building. Now the legal issue related to the project notice (required to obtain permission for demolition) has become a question to be tackled more on the political than on the administrative level.

Cases of ‘expropriation for public utility’ have been brought before the court and are still in process in Bucharest. Bearing in mind the traffic problems in the city, the City Hall considers that the solution is widening the streets, despite criticism from the civil society. However most of the expropriation in these cases involves empty fields, not built houses. So the public is relatively unaware of the expropriation and there is little talk about it.

1Sorin Oprescu expressed these views concerning the Matache neighborhood in a statement made to the press.

2The North-South middle line is an infrastructure project with a total length of 12.5 km, aimed at connecting north and south Bucharest. The project will connect two main administrative buildings - the Parliament AND the Government. Officials in the City Halls publicly presented the project as an alternative for a nearby historical street, overcrowded with cars. The project was initially designed in the 1930s and is being implemented now, although the urban fabric has changed considerably since then. It is to be implemented in three different stages: the first, with a total length of 1.8 km, was implemented between 2010 and 2014 and was highly debated within local civil society because it led to the widening of an existing street by demolishing dozens of buildings. The next phase will be the creation of a 900m length tunnel underneath the Palace of Parliament (The House of the People). This part of the project is now under debate because it will raise costs (the tunnel is a new one and it requires expensive procedures). The last part of the project is not yet envisaged, but it will require further demolitions.

3The composite demographics of a defined area, which consists of its ethnic composition, wealth, education level, employment rate and regional values.

4Bucharest is divided into 6 different districts. The General City Hall coordinates the biggest local budget and is responsible for big infrastructure projects.

5The Code for the Civic Procedure stipulates (Art. 578) that no person can be evacuated in the period from the 1st of December to the 1st of March except for urgent public matters and provided the people to be evicted will have a proper place to live.

6According to Romanian legislation, the building was considered to be class B, meaning of local historical importance, and therefore it was protected by the legislation.

7The document was compulsory for the General City Hall in order to obtain permission for demolishing the building.

Sources

To go further

Bindean I.R., Alavi S.L., Tirnovan T., 2012, Matache - Northern Station Area, Regeneration Debate, Bucharest, Romania, Manchester School of Architecture.

Lumpan D. (2016), Matache – Berzei Buzesti. Documentary film.

A website developed by volunteers that gave a thoroughly account on the story: www.facebook.com/events/127473583989156/

Protests’ videos: