The Climate Conferences - Presentation of equal carbon quotas

Session 7

Pierre Calame, marzo 2021

From the fifth session onwards, the three « families » of possible solutions for achieving the performance obligation, i.e. a cap on greenhouse gas emissions, calculated in terms of tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, with a constant annual reduction of around 5 to 6%, were examined, one per session.

-

The first family (session 5) is called »price signal ", because it is by constantly increasing the price per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent that the result is expected to be achieved.

-

The second family (session 6) called « sectoral approach » is the continuation of the policies carried out over the last thirty years, with a combination of public investments, incentives and bans acting on the three categories of emitters : citizens, companies, public services.

-

The third family consists of acting globally by allocating to each person an equal CO2 equivalent emission quota for all, with a reduction of this quota at a rate of 5 to 6% per year. This is the subject of this seventh session.

Para descargar: cucchi_contenir_la_pression_des_interets.pdf (300 KiB), huchede_calcul_empreinte-carbone_.pdf (63 KiB), huchede__lecarbometre.pdf (510 KiB), languille_compte_carbone_shifters.pdf (120 KiB), menard_construction_neuve_decarbonation.pdf (960 KiB), questionnements_session7.pdf (90 KiB), quotas-fil_conducteur_session7.pdf (220 KiB)

The inclusion of the seventh session in the cycle as a whole : continuity and breaks

This seventh session is a continuation of the other two on two major points :

-

all of them start from the requirement of an obligation of result ;

-

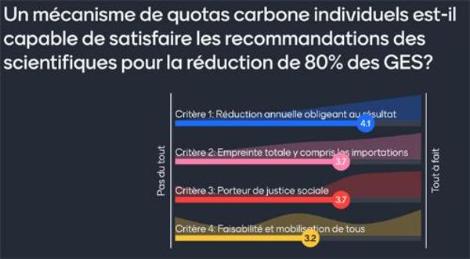

the effectiveness and feasibility of each family is analysed in the light of four common questions : capacity to achieve the result and to manage rationing ; capacity to take into account the entire ecological footprint (carbon dioxide emissions and other greenhouse gases, mainly methane and nitrous oxide) ; social equity and capacity to decouple the well-being of all from greenhouse gas emissions ; capacity to mobilise all the players.

In addition to these elements of continuity, the third family analysed today has a major difference from the other two: the issue of rationing emissions, common to all families since it stems directly from the obligation to achieve results, is here considered through « rationing of demand ». Although this type of strategy has been discussed several times over the past twenty years, and was even put forward for a limited time in the United Kingdom by an economist, David Fleming, in the 1990s, and taken up by the Labour Party, led by the then Environment Minister, David Milliband, in the first decade of the 2000s, the defeat of the Labour Party in 2010 put an end to the political debate on this subject (see Mathilde Szuba’s work).

The introduction of individual tradable quotas does indeed imply a certain number of breaks with the dogmas of classical economics ; it is even its major interest. The other two families, discussed in sessions 5 and 6, have in common that they postulate the need for major transformations of the economic system and lifestyles while, in practice, remaining within the continuity of traditional modes of economic action and governance : taxation, investment, regulation. Pierre Calame reminds us in his introduction that this idea of tradable quotas has been defended for years in France, on the one hand by Mathilde Szuba, who made it the subject of her thesis (see her article on the Assises website), and on the other hand by himself in his 2009 book « L’essai sur l’oeconomie » (chapter corresponding to this idea also on the Assises website). Left fallow, it has been attracting growing collective interest for the past year, initially on the occasion of the Citizens’ Climate Convention, CCC. Armel Prieur and Vianney Languille are leading collective reflections on the subject.

The four major breaks introduced by quotas

Let us recall four of Einstein’s aphorisms: a new way of thinking is essential if humanity is to live; to invent is to think outside the box; we must not rely on those who created the problems to solve them; madness is doing the same thing all the time and expecting a different result. These are the questions that have marked the debate on the first two families: can we make radical changes, « essential if humanity is to live », while remaining within the framework of thought inherited from the last two centuries? And, after thirty years of exhausting ourselves in defining strategies to reduce the ecological footprint of our societies without achieving any significant results, why should we expect a different result today by continuing to apply the same recipes? Is it not more reasonable to revisit our economic thinking in the light of the new challenges facing humanity ? It is this effort that determines the first three ruptures :

-

when the oeconomy loses its o

The term « oeconomy », used until 1750 to talk about what was later called « economy », had the merit of recalling its etymology, very well commented by the botanist Karl Van Linné : to ensure the well-being of the whole community in a context of limited resources. In the 16th and 17th centuries, there were many works on « rural oeconomy », which today would be called « strong agro-ecology », explaining how to organise the life and production of a rural estate in such a way as to ensure the well-being of the whole community while maintaining the fertility of the soil and the biomass resources. The fall of the oeconomy coincides, around 1750, with the take-off of the industrial revolution which, by substituting fossil energy for animal and human energy and by mobilising the resources of the whole planet, was able to maintain for two centuries, in the only developed countries, the illusion of infinite resources. The challenges of the 21st century are strangely similar to those faced by mankind up to the industrial revolution, on the understanding that we must take up these challenges by mobilising our scientific knowledge and technologies to the best of our ability, as advocated by Karl Van Linnaeus, in order to organise what must be called the « great return to the fore » of the economy.

-

You don’t drive a nail with a screwdriver and a screw with a hammer

One of the essential precepts of oeconomy is that each good or service should be governed according to its true nature. Classical economics distinguishes only two types of goods and services: « private » goods, managed by the market economy and the balance between supply and demand; and « public » goods, which must be managed by the community. This typology is too simple. In reality, four types of goods and services can be distinguished. Given the impact of greenhouse gases on climate change, we must, as the very idea of an obligation to achieve results indicates, start with a ceiling, and therefore rationing. And to do this, we need to design the governance system best suited to this rationing, i.e. the one that best reconciles the result to be achieved, the well-being of all, and social justice.

-

You cannot drive a car where the brake and accelerator are the same pedal

In other words, it is illusory to use the same currency to pay for « what needs to be developed ", essentially human work, which is the basis of the well-being of all and of social cohesion, and « what needs to be saved » greenhouse gases. The need for two different currencies is alien to mainstream economic theory.

The debates held during the first sessions of the Assizes revealed a fourth rupture :

-

Supply-side rationing or demand-side rationing ?

Since the Kyoto Protocol, international negotiations have all focused on so-called « territorial emissions of greenhouse gases », which are subject to inventories according to a number of internationally defined methods. As this approach is concerned with emissions on European soil, it necessarily focuses on those who are at the source of these emissions. In practice, there are three main categories of actors: the citizens themselves; the production system; and the public services and administrations. This leads to the implementation of a set of measures to restrict supply.

The perspective opened up by the Assises, in line with the work carried out in 2020 by the High Council for the Climate, is no longer about territorial emissions but about our responsibility towards the climate. As shown in the sixth session, this responsibility stems essentially from our « ecological footprint », all the greenhouse gas emissions linked to our way of life and the functioning of our society, to which are added two subsidiary responsibilities: the fact of exporting goods and services with a high carbon content; the investments we make abroad, in particular to promote the extraction and processing of fossil energy.

As society’s ecological footprint is our primary responsibility, it includes the « imported » ecological footprint, incorporated without our always being clearly aware of it in the production, transport and distribution of the goods and services we consume. From then on, the central actor becomes the citizens. It is therefore a question of rationing demand, with the other actors, companies, public services and administrations, being in a sense only intermediaries. It is the action of citizens, once they have knowledge of the ecological footprint incorporated in the goods and services they buy and in the public services from which they benefit and which they finance, which is the trigger, the lever for all the other transformations.

A collective dynamic led by Armel Prieur and supported by the website www.comptecarbone.org

Since the beginning of 2020, this dynamic has multiplied dialogues with a large number of organisations and networks such as La Bascule, Géopolis in Brussels, networks of architects, the association Agir pour le climat, the Rousseau Institute, the association Bilan Carbone, etc. Meetings have also been organised with members of parliament, political parties and the Prime Minister’s office. It was during these many contacts that objections to the proposal for individual tradable allowances were collected, objections that sometimes concerned the principle itself, sometimes its feasibility. It is these objections that have gradually led to the identification of possible responses in terms of both the technical tools and the governance of such a system, it being understood that these are, by definition, only hypotheses subject to debate. Indeed, today it is above all a question of introducing public and political opinion to the prospects opened up by these individual negotiable quotas with a view to a civic and political debate whose vocation it would be to transform this proposal into a concrete mechanism.

More recently, this collective dynamic has been joined by another, led by Vianney Languille, member of the « Shifters » association. This network of volunteers is made up of several thousand people and is an extension of the Shift Project, an association created and led by Jean-Marc Jancovici, financed by major French companies and which aims to propose a strategy for decarbonising the economy. Within the Shifters association, the reflection on the carbon account is conducted independently. Led from Toulouse, it is interested, to use Vianney Languille’s expression, in how to move from an attractive concept to the complexity of real life with eight working groups on the following subjects : social and political acceptability ; communication ; carbon labelling of goods and services ; imports and exports, in particular the possible interactions and synergies with the European carbon market (ETS - EU) ; management of private individuals’ carbon accounts ; economic evaluation of the system’s impact.

The speakers of the session

They are the emanation of these different working networks and their contributions complement each other as we will see :

-

Armel Prieur, retired from the European Council, president of the association for carbon-free employment

-

Mathilde Szuba, economist, whose thesis stimulated interest in France for quotas ;

-

Vianney Languille, engineer at Airbus and member of the Shifters ;

-

Michel Cucchi, Director of a hospital in Lille and who was particularly interested in the governance of such a system ;

-

Christophe Huchedé, creator of the carbometer which allows each person to calculate, from ADEME data on the footprint of the different sectors, the carbon content of their consumption ;

-

Frédéric Ménard, specialist in building materials, president of the association Agir pour le climat founded by Jean Jouzel ;

-

Jean-Luc Fessard, a long-time activist in ecological movements (he participated in the foundation of Friends of the Earth in the 1970s), president of the association « Good for the climate » which campaigns for a change in food practices in order to preserve the planet and its climate.

The general economics of tradable individual allowances

The economics of the scheme are set out in the leaflet entitled « Allocating tradable allowances to all to drive the energy transition » at www.assisesduclimat.eu. The principle is simple: rationing by demand while respecting social justice. The drivers of the transition are therefore the citizens themselves, the ultimate beneficiaries of goods and services, who will, through their consumption decisions and the pressure they exert on the public authorities, bring about a transformation of production systems and governance. To this end, each citizen (with a percentage to be determined for children and adolescents) receives annual « carbon points » equal for all and which determine their « right » to consume goods and services whose production and delivery each contain a share of greenhouse gases, within the total annual allowable emission of these greenhouse gases in order to respect the ceiling corresponding to our society’s responsibility towards the climate. These annual quotas, in order to assume our responsibility towards the climate, are reduced by 5 to 6% each year, which represents a radical break with the inability of our society, whether European or French, over the last thirty years, to reduce its dependence on fossil fuels and economic activities, particularly agriculture, which are high emitters of other greenhouse gases, particularly methane, CH4, and nitrous oxide, N2O.

With this system, which is characteristic of all rationing and which can be found, for example, in fishing quotas to preserve fish stocks, any good or service consumed, whether private, through a purchase, or public, through the payment of taxes, corresponds to a double debit, in euros on the one hand and in « carbon points » on the other. Thus the carbon ton equivalent is a currency in its own right - a unit of account, a means of payment and even a store of value - but a currency which, as in a parlor game, is subject to an annual allocation to each player. The use of several currencies is not at all exotic, as is already the case with loyalty cards which collect and debit « miles » or loyalty points.

In such a system, and this is the radical difference with the rationing of supply, as presented for the other two families, companies and administrations do not receive annual allocations. They must keep a register of inputs and outputs, produce greenhouse gases for the production, transport and distribution of these goods and services, take these same gases into account in the intermediate goods and services they purchase and must incorporate in the selling price or in the taxes and duties the corresponding quantity that will be debited to the account of the customers or taxpayers.

This register takes into account the quantity of greenhouse gases involved in the production of the goods and services that are imported before they enter the European or French territory (depending on whether the system is conceived at the European level or the level of a single country). This is not a border tax, which makes the system fully compatible with bilateral and multilateral trade treaties, but rather a fair accounting of emissions wherever they occur, as long as they contribute to the goods and services purchased by the population of the territory. This system is the only one that satisfies both the obligation of result, since it is the very basis of the establishment of quotas, and social justice.

It is based on the freedom of choice and decision of each individual in two ways. First, unlike a rationing system for a single good or service, such as air travel rationing, it is up to each individual to make choices within their own quota. Secondly, the most frugal individuals and families who do not spend their entire quota can sell the surplus to those who wish to maintain a more greenhouse gas-intensive lifestyle. But it is obvious that with a reduction of 5 to 6% per year, this implies in any case for all : a profound change in energy sources in favour of renewable energies ; an evolution of all towards sober lifestyles ; a rapid increase in the price of the ton of CO2 equivalent for those who will want to consume beyond their quota. But, unlike the other two families analysed in the previous sessions, this carbon price is observed at the time of the exchange of allowances, it is not the price that guides the evolution of the system.

It is not the rise in the price of carbon that forces the production system to restructure, but the fact that companies whose goods and services incorporate a lot of greenhouse gases in their production will no longer find takers on the market, as consumers do not have the carbon points needed to pay for them.

We can therefore speak of a leverage effect (Archimedes used to say: « Give me a lever and I will lift the world ») which will produce, from one step to the next and with the speed necessary to preserve the climate, a complete restructuring of companies, production systems and public services.

To measure the scale and speed of the effort to be made by finally taking our responsibilities seriously, it is sufficient to recall that in France the ecological footprint is estimated (most recent report by the Ministry of Ecological Transition, December 2020) at around 10 tonnes per inhabitant per year, which we have committed to reducing to 2 tonnes by 2050 (see on this subject the presentation by the High Council for the Climate during the first session of the Assises). However, today, the greenhouse gas content of the public services of the State and local authorities is estimated at between 1.4 and 1.7 tonnes per year and per inhabitant : three quarters of the available allocation for each person in 2050 ! As Christian Gollier reminded us during the third session of the Assises, assuming an obligation to achieve results will involve a radical upheaval in production systems and lifestyles. Not to say this and give the impression that it will be enough to develop renewable energy, which also creates jobs, is to lie and to lie to oneself.

Let us now turn to the examination of the answers given during the session to the four questions common to all the families of solutions

A/ Capping and obligation of result

Of the three families of solutions studied, this is the only one that is based directly on the obligation of result. Let us go further. As Mathilde Suzba points out, « the climate issue is, generally speaking, something that we reject from our consciousness, that is beyond our limits of representation, something over which we have no control. On the contrary, the quota system is an extension of the global objective of preserving the integrity of the environment down to the level of individuals: everyone has a tangible part to play and is involved in saving the planet in a concrete and personal way.

Is there not a risk that this system will gradually be distorted by taking into account specific situations, thus opening a Pandora’s box into which all the lobbies will fall? Armel Prieur recognises the existence of this risk, for example when we are tempted to take into account differences in situation, for example, town or country. We know that a robust, independent system, a carbon agency, will have to be set up, otherwise, hiding behind social considerations, the offensives of special interests will rush in, says Michel Cucchi. We need a profound renewal of public action based on a concerted management of the commons, a multipartite approach with a strong ethical component (which is in line with the discussion in the third session on the responsibility of the various actors) and a profound renewal of the training of public agents, with a common core on the vital issues of humanity, a condition for the creation of a common culture. The current generation of civil servants, as Mathilde Suzba said of the citizens themselves, is confronted with questions so vast that they are not aware of them.

How to guarantee the continuity of the process beyond political alternations ? This question is found in all families of solutions. In this case, the implementation of a counting system for a physical quantity makes it impossible for political changes to take place. Armel Prieur wondered whether, in order to avoid the consequences of political changeovers, the greenhouse gas emission reduction trajectory should be given a special formality by submitting it to a referendum. It was also observed during the previous sessions that the strength of decisions taken at European level would be to define a multi-annual framework which would then be binding on national governments regardless of the changeover.

Will this mechanism have a leverage effect to bring about a change in the technical system and in public investment and innovation strategies? We have seen in previous sessions the challenge of a change in the technical system, combining innovations in different fields, for example in electricity production. The leverage effect of individual quotas reduced each year will give both predictability of evolution and an incentive to find alternatives, which will accelerate the change of the technical system. Negawatt has shown, for example, that it is technically possible for a country like France to achieve 100% renewable electricity, including the intermediate storage and grid regulation mechanisms necessary for the intermittent nature of this energy production. As soon as the total greenhouse gas cost of electricity production is translated directly into carbon points for each citizen, this technical change will no longer be a hypothesis but an imperative.

At what political scale is the system relevant? Because of the single market, the European level is the most natural and effective. The importance of the European market also suggests that it could have a global impact. One only has to think of what it will mean in terms of changes in the global production chain to really take into account the greenhouse gases incorporated in products and services when they enter the European territory.

Can we nevertheless start with one or more countries? This is what Armel Prieur thinks. According to him, the existence of national accounting systems would allow a few European countries to decide to adopt this mechanism as a start.

Despite the urgency to act, should we plan for a test year in which everyone is informed of their greenhouse gas consumption without yet introducing it into the means of payment? Yes, » says Armel Prieur. Rather than a test year, he prefers to speak of a « year without sanctions » to implement metering.

B/ The total footprint of companies

The system of individual tradable allowances requires that greenhouse gas emissions, mainly carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide, be recorded throughout the supply chain. Is this possible?

In the French case, the question was addressed in the first session. We now have global information on our ecological footprint, based on the ADEME’s « base carbone » (www.ademe.fr/base-carbone) whose methodology is refined every year. It determines the so-called « emission factors » attached to each product. This data is an average taken from the national economy matrices, which does not currently allow for effective traceability linked to the particular products that are purchased, and does not reflect the efforts made, within a production chain, by any particular company.

Nevertheless, this has enabled Christophe Huchedé to create the carbometer (available on the website www.assisesduclimat.eu). Based on ADEME data, this carbometer allows each person to calculate his or her « GHG balance », a fixed estimate of his or her ecological footprint, deducted from his or her consumption. It can therefore be seen as the forerunner of the tools for calculating the actual footprint, which will be used in the context of quotas to evaluate the carbon points attached to each consumption. It is already a powerful tool for raising awareness.

The carbometer was first created in the form of a spreadsheet and now in the form of a web or smartphone application. It adds up GHG emissions for an annual assessment based on our four areas of consumption : transport mobility ; housing ; food ; one-off purchases of goods and services. For each type of good and service, the carbometer indicates, among other things, the degree of reliability of the emission factors taken into account : a low uncertainty for cars, for example, but a much higher one for food. One of the major uncertainties concerns capital goods, whose emissions must be spread over several years and for which the equipment’s lifespan is an essential factor. Here again, the system of individual quotas has a considerable leverage effect to provoke life-cycle analyses of products (with recycling playing a role in receiving or not receiving carbon points at the end of the products’ life) and to move towards durable capital goods.

Is it possible to have an overall assessment of ecological footprints at the European Union level, as is the case in France? The High Climate Council has drawn up a graph of the ecological footprints of the various European countries. The ecological footprints vary considerably : just over 5 tonnes of CO2 equivalent for Romania and 25 for Luxembourg, which is an extreme and isolated case, with most European countries in a narrower range, between 7 and 15 tonnes per inhabitant per year. population, climate and current electricity production systems. The graph also shows that countries with a reputation for being « green », such as Sweden and Denmark, both have a larger ecological footprint than France, with Sweden’s footprint being close to that of France and Denmark’s being close to 15 tonnes. As we can see, the ecological footprint approach corrects the image given by countries when we stick to territorial footprints alone. It can be assumed, but it remains to be verified, that this type of detailed analysis already exists in most EU Member States.

How are companies driven to ensure traceability of fossil energy consumption along the supply chain? One of the arguments put forward by opponents of the idea of individual quotas is that it is impossible for companies, which are part of global production chains involving thousands of suppliers and subcontractors, to ensure complete traceability of greenhouse gases. Two answers have already been given to this objection. The first was given by Pierre Calame, who pointed out that the equivalent can be found in the VAT: it was not because VAT was easy to charge throughout the production chain that the tax was created, but because there is a tax that it has become easy to charge VAT throughout the production chain. The second point made by Christian De Perthuis: a strong way of encouraging traceability is to use a maximum scale in the absence of traceability (this is the logic of the « motorway ticket »: the person who loses his ticket pays the maximum distance).

Jean-Luc Fessard illustrated the power of the leverage effect in the restaurant industry. Convinced that nothing will happen without citizen initiatives to raise awareness of our impact on the climate, he and his association « Good for the Climate » decided to focus on food, which weighs heavily in our ecological footprint, about 1/4 of total greenhouse gas emissions, particularly due to the high impact of methane and nitrous oxide, and which directly affects daily life. To organise this awareness-raising campaign, he had the idea of mobilising restaurant chefs, to whom the association provided a tool for measuring the GHG impact of their cooking. This tool enables four criteria to be evaluated : taste quality ; the shift towards less meat-based food ; respect for the season and local sourcing.

The interest of this tool is that it is no longer a flat rate: for example, in terms of livestock farming, there is a major difference in emissions between intensive industrial livestock farming and pasture farming. The method of production and conservation is also essential: nitrous oxide emissions are linked to chemical inputs and emissions of fluorine derivatives, refrigerants, which also play an important role, are linked to the cold chain.

The interest of the detailed approach to the ecological impact of food is to highlight in a very tangible way the impact of the type of agriculture, which could be largely influenced by a reform of the European Common Agricultural Policy, that of eating habits, with the evolution towards a less meaty diet, and the social acceptability of an approach based on seasonal products (we find again the reflection carried out in the sixth session on needs : simply not wanting « everything right away »). The commune of Malaunay tested three families for three months by providing them with the tool for measuring the ecological impact of their food. After three months, each family had reduced its footprint by 30%, regardless of its initial footprint.

How would payments be made in two currencies? Technological developments are underway to support this. The ecological impact of the traceability system itself needs to be assessed, but the rapid development of mobile phone payments, accelerated by the Covid pandemic, means that the use of the individual quota can be included in technical developments that are already underway, including those relating to data protection.

How to evaluate or control the carbon price ? Pascal Dagras emphasised that the Climate and Resilience Bill could take up the first proposal of the Citizens’ Convention, which calls for the introduction of a carbon score. In this respect, he mentioned a project that would aim to mobilise collective intelligence : similar to what is happening with the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia, a collaborative system, involving citizens, companies and associations, could make it possible to describe and calculate the carbon price of a maximum number of products and services and to ensure that the prices displayed are consistent.

C/ Social justice and decoupling

Whatever solutions are adopted, they must make the obligation to achieve results compatible with social justice and allow for a decoupling between the development of well-being and fossil fuel consumption.

As Armel Prieur reminds us, the question of social justice is at the heart of the debate on quotas because it refers more fundamentally to the question of the ownership of the global commons. The first ideas on the subject date back to the 1980s. The great Indian ecologist Anil Agarwal asked the question: « Who owns the carbon sinks? We know that, to use Michel Rocard’s expression, the planet would already be a frying pan without the regulating role of the oceans and the great steppes or primary forests that absorb, until today, the bulk of carbon dioxide emissions. This means that the richest societies, and within them the richest social classes, are taking over the carbon sinks. If there is one conviction shared by the proponents of the different families of solutions, it is that none of them will succeed unless they are accompanied by social justice.

Illustrating her point with relatively old data, Mathilde Suzba reminds us of this in relation to France. The graph below shows the impact of the energy budget on the total household budget, i.e. the « effort rate », divided by income into five quintiles in 2001 and 2006, i.e. during a period of rising oil prices.

For the first quintile, this rate was 10.2 in 2001 and 14.9 in 2006 ; for the fifth quintile, despite the increase in the price of energy, it fell from 6.3 to 5.9, the increase in income having more than compensated for the increase in the price of energy (Source ADEME et vous ; stratégie et étude 3 avril 2008).

On the other hand, the carbon footprint increases with income. The graph below for the year 2010 illustrates this with the same breakdown into quintiles : less than 4 tonnes for the first quintile and almost 10 for the fifth.

Selected expenditures. Expenditure on housing is increasing relatively slowly, expenditure on mobility is increasing very rapidly.

The weight of the consumption of the richest in the evolution of the ecological footprint is also illustrated by two graphs proposed by Michel Cucchi. The first, based on Thomas Piketty’s work on global inequalities, shows how the fruits of growth between 1980 and 2016 were distributed on a global scale.

During this period of growth in emerging countries and stagnation, or even regression, in the incomes of the middle classes in already developed countries, the poorest 50% of the population captured 12% of the growth, while the wealthiest 1% alone captured 27%. This largely explains another graph presented by Michel Cucchi and taken from a study (controversial in detail but certainly illustrating the orders of magnitude)

On a global scale, the poorest 50% of the population are responsible for 6% of the total growth in emissions over 25 years, the 40% of the population corresponding to the middle classes are responsible for 49% of the growth in emissions (the European population is massively in this bracket), and finally the richest 10% are responsible for 46% of the growth in emissions.

These data show why equal tradable allowances for all have a massively redistributive effect. It would be demagogic to pretend that in Europe the reduction of the total ecological footprint by 80% by 2050 will not impact on the lifestyle of the middle classes : over 25 years, even a modest increase in their income has resulted in a significant increase in their ecological footprint and this process will have to be reversed. But this effort will be gradual. The impact of the quotas is, on the other hand, immediate for the richest, who will have to change their lifestyle rapidly and radically, finding it increasingly difficult and at a necessarily very high price to find people willing to give up a surplus quota. As Mathilde Szuba points out, giving the same share to everyone highlights the interdependence between consumers, clearly putting on the table « conflicts that already exist but are hidden in terms of environmental inequality ". It also confirms that starting to take exceptions into account in the name of the incompressible needs of this or that category of population would open the door to a general drift. Hence the importance of a central system independent of politics managing the allocation of carbon quotas. Furthermore, the annual rate of reduction of quotas over 30 years will give a high degree of visibility to the efforts required of the various social groups, and will give them a clear vision of the transformations of all kinds implied by the reduction of quotas. States are then free to implement a fiscal policy that takes into account the increase in income inequalities over the past 20 years, in order to give the least well-off population the means to adapt to the reduction in quotas.

The presentation we have adopted of the three families examined one after the other may give the impression that one excludes the other. This is not the case. In particular, not only do quotas not exclude the use of solutions from the second family, but they also provide a powerful incentive for their development: the substitution of renewable sources of electricity production, thermal insulation of housing or new forms of mobility.

As for the decoupling of the development of well-being and the reduction of the ecological footprint, it is precisely the use of two different currencies, one that allows for the development of employment and all the benefits of low-carbon technologies and the other that allows for the reduction of the ecological footprint that creates this automatic decoupling.

Is the system practicable and does it not risk creating a complicated monster to manage, or does it not lead to the policing of the population? A computer scientist linked to local currencies who wished to remain anonymous pointed out that the practice of dual currency already exists, with the local currencies that are developing now having an electronic medium and the use of a unique consumer identifier already being brought into compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

The Covid pandemic has, moreover, given rise over the past year to a tremendous development of mobile phone payments in Europe, where it was lagging behind, and it does not seem very complicated to design mobile phone applications adapted to the use of a dual currency, any more than it seems complicated to modify the cash registers of large retailers once the upstream calculation has determined the carbon points associated with each product. This computer scientist also points out that the idea of carbon quotas is generally well received in the world of local currencies, partly because of the habit of using two currencies and partly because local currencies themselves are based on a philosophy of decoupling different types of consumption.

The transport of carbon points by bank card is also under discussion with Mastercard. It will have to be tested by a mock-up or pilot of the computer system. Cash register software publishers such as 3Dcom are very interested in adding carbon information to their software.

D/ Mobilisation of all players

As with the other two families, a policy based on individual tradable allowances needs to ensure that the proposed change is physically possible, that it is clear what it will mean for each actor, and that everyone is invited to participate by taking their share of responsibility.

As has just been pointed out, not only is the system of tradable quotas not an alternative to the technical reflections carried out in the sixth session, but on the contrary, the two approaches complement each other, with individual tradable quotas providing the leverage that has so far been lacking in all the fine technical scenarios. By way of illustration, Frédéric Ménard, who is a great specialist in this field, illustrated what it would mean to guarantee the decarbonisation of « the value chain of new constructions » by applying it to the case of cement and concrete.

He recalled that the objective of the National Low Carbon Strategy (NLCS) is to reduce from 11 million tonnes of CO2 emitted by the cement sector in 2015 to 2 million tonnes in 2050, a reduction that is proportional or close to the overall reduction of the ecological footprint. To achieve this, three types of levers are available : a technical lever, leading to a reduction in the ecological footprint of a square metre of building by improving the carbon footprint of the production of a tonne of cement, by reducing the proportion of cement in concrete, by reducing the proportion of concrete per square metre of building ; a lever linked to lifestyles, by reducing new construction, and therefore the number of square metres of buildings per year, reversing the trend which, until now, due to the low cost of fossil energy, has tended to increase the surface area of housing per inhabitant from one decade to the next ; a lever for CO2 sequestration in new construction. According to him, the third lever is limited. From a technical point of view, whatever the technical efforts made by the building industry, it will not be able to reduce the number of square metres per year below 5 million tonnes. This leaves a gap of 3 million tonnes to get down to 2 million tonnes per year.

The interest of the individual tradable quota approach is, according to him, to transfer power and responsibility to the « customers » who will be able to accelerate the reduction of the ecological footprint of concrete production on the one hand, and on the other hand to change the construction sector by encouraging the multi-use of the square metres built, by increasing the rate of use of buildings, by stopping destroying and rebuilding at the same rate as we are doing it, by reducing the number of square metres of new construction per year in these different ways.

All this requires the development of extra-financial reporting by the building sector. In any case, he says, quotas will force us to reason about the final result and not only about the reduction of emission factors per unit of material. This is a striking illustration of what had emerged in the previous sessions : the effort to reduce emission factors by economic sector favours technical optimisation approaches but overlooks the other aspect of the transformation, the restructuring of the economic system itself.

All speakers agreed that the quota approach has the advantage of putting citizens themselves at the heart of the transformation process. Tools such as the carbometer give them full information on their role, in a context, well described in the previous sessions, where citizens themselves lack information or even awareness of the levers available to them.

What would be the role of the territories in leading the transition? In his work, Pierre Calame suggested that the Regions could be the first level of creation of carbon trading exchanges. It is not certain that they are prepared for this today, but there was a consensus during the session on the importance of the emergence, in various countries, of local committees where all these simulations could be developed, leading to a broad awareness among the population, without which nothing will happen.

Armel Prieur also noted that the idea of regional carbon exchanges had been well received in Toulouse and Bordeaux, but that this would require the massive recruitment of advisors to run all these local committees. This would be a priority of the recovery plan, including from the perspective of youth employment.

How, finally, will the administrations and public services be led to assume their own obligation of result? Armel Prieur cited the order of magnitude already mentioned: in France, public administrations and services account for 120 to 140 kilos of CO2 per inhabitant per month, i.e. approximately between 1.4 and 1.7 tonnes per year per inhabitant. Under the quota system, this is as many carbon points deducted annually from each inhabitant’s quota. It is easy to imagine the pressure that will be exerted on administrations and public services. The very logic of equal quotas for all suggests that the carbon points allocated to administrations and public services will themselves be distributed equally among all (otherwise, with the progressivity of taxation, a whole section of the population would find itself with negative quotas once taxes have been paid !) Even in sectors such as defence (35 kilos per month per inhabitant) and hospitals (17 kilos per month per inhabitant), a radical change in the defence and health systems must already be envisaged.

Referencias

-

Mathilde Szuba brings her vision as a political scientist specialising in rationing mechanisms

-

Michel Cucchi extends the subject to health issues and its complementarity with European funding (see document Containing the pressure of interests) ;

-

Vianney Languille presented the interest in shifters and the setting up of working groups that he has been leading since October (see document ,

-

Christophe Huchedé creator of the Carbometer to calculate its footprint and build carbon contents (see the document calcul_empreinte-carbone.pdf),

-

Frédéric Ménard on how the construction sector will react to generalised carbon metering (see the document Construction_neuve_decarbonation.pdf)

-

Jean-Luc Fessard describes the experimentation of low-carbon restaurants gathered in Good for the Climate.

Para ir más allá

Anyone can draw on the open resources of the conference to develop publications or viewpoints. Please cite the contribution of the Climate Conferences.

Nine two-hour sessions are posted in full on facebook of the climate conference