London Green Fund: attracting private capital through low-carbon European public investment

2014

Fonds mondial pour le développement des villes (FMDV)

Though little used during the previous budgetary period (5% of the ERDF), the European Commission is seeking to develop its Financial Instruments (FI) for the 2014-2020 period.

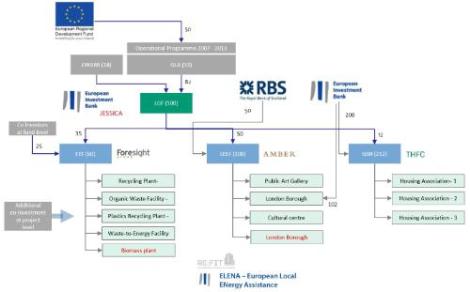

The European financial instruments seek to provide local governments with investment aid, especially via loans, guarantees or capital, sometimes combined with technical assistance, interest rate subsidies or guarantee fee subsidies within the same operation. Objective: to create an alternative to subsidies and attract private investors The London Green Fund is an investment fund of €125 million, managed by the EIB. It supplies three other specific funds managed by private bodies and dedicated to waste management, energy efficiency and the renovation of public buildings. Designed to accompany London’s political commitment to reduce its CO2 emissions by 60% by 2025, it is part of the JESSICA initiative1, a European financial instrument that seeks to mobilise private investments to fund low-carbon projects and to create converging dynamics for sustainable local economic development.

À télécharger : local_innovations_to_finance_cities_and_regions3.pdf (1,5 Mio)

The European financial instruments (FIs) have been re-oriented to better meet the needs and specific capacities of European regions2. They are designed as direct links between regions and European funds, and as catalysts to improve investment performances. Each of the FIs has a scope of action and model of implementation that is specific, but they share broad common principles that structure their approach. These include the principle of recycling funds (revolving funds), which enables regions managing structural funds to use some EU subsidies for long-term investments. This way, they generate the leverage needed to attract a broader diversity of public and private investors that are often reticent about getting involved in projects considered not very attractive, all the while limiting contribution from public resources. The assigned objective is to reach the levels of strategic investment needed, in the regions, for the implementation of the “Europe 2020” orientations.

Financial architecture that acts as a catalyst and is linked to the sustainable objectives of the area

The London Green Fund (LGF) is an initiative of JESSICA3 and has been operational since 2012. The fund is fuelled by the ERDF (€62.5 million); the Greater London Authority (€40 million); and the London Waste and Recycling Board (LWARB), which is the public organisation in charge of London waste management (€22.5 million). The LGF includes three urban development funds (UDFs), each of which has a specific scope of action and mandate to finance projects directly through equity investments and loans4. The funds revolve (differently for each of the three UDFs), so that their returns can be reinvested in new projects to support. The UDFs are managed independently by private fund managers chosen by the LGF and supervised by an LGF investment office. These managers are also in charge of securing complementary public and private capital according to needs. The use of UDFs is subject to operating rules, such as the ceiling on the co-financing amount or quantified objectives that involve financial commitments (e.g. €1800 invested by the LEEF5 must reduce CO2 by 1 ton). Furthermore, the funds must respect the principle of additionality, i.e. ensure the diversity of the London urban projects supported. Moreover, within the framework of the FIs, the management authorities undertake to plan for evaluation and monitoring of the implementation of the projects funded, at very detailed levels (contracts, technologies, etc.) to evaluate their impacts, especially for the environment, and to avoid possible failures. Launched in 2007 and set up in October 2009, the LGF has not yet been subject to an evaluation, because the first operations started only in early 2012. Nevertheless, it is estimated that the €125 million leveraged from the fund will inject €360 to 500 million into London’s low-carbon economy6. In 2013, around 10 projects were funded by the three UDFs, including an organic waste treatment plant and the renovation of a public art gallery.

Source : FMDV

Closer support for projects required, and project management by local governments called into question

It quickly became apparent that support for the project implementers, which had not been provided for in the LGF procedures, was essential. The operational environment of the financial instruments (quality and degree of maturity of the projects), as well as the administrative capacity and technical expertise required for their optimal implementation, varied to a great extent once confronted with local realities. Validating project applications thus turned out to be more complex than expected and delayed the implementation of the funds. For example, while the mobilisation of expertise needed to determine the exact budget of the infrastructure renovation funded by the LEEF struggled to get off the ground, the Waste UDF projects were delayed due to non-alignment in agendas among the contracting parties: those that take care of supplying waste on the one hand, and those providing the customers for electricity produced by biomass on the other. These needs in training and support, which are crucial for the success of investment operations as well as their financial viability and credibility, require the fund-managing bodies to have the available in-house expertise and human resources able to meet them. These, however, represent an extra cost that impacts the financial balance and flexibility of the local investment fund. Following the evaluation of the impact of FIs and their adaptation to local needs, the EIB now recognises that synchronisation is required between technical assistance for the preparation and funding of projects on the one hand, and the political strategy that led to the choices of the projects selected on the other. A final point: the choice of projects is made on the basis of their economic and financial viability, but its connection with the strategic planning of land-use management is questioned, bringing up issues in terms of coherency and the local government’s management of its local development. Community projects, which often lack suitable financial engineering, thus find themselves quickly eliminated from the validated lists of candidates for UDF funding7.

Source: EIB website

Source: FMDV, 2014

1 Joint European Support for Sustainable Investment in City Areas (JESSICA)

2 Four joint initiatives were developed by the European Commission (Directorate-General for Regional Policy), in cooperation with the European Investment Bank Group and other financial institutions within the framework of the 2007-2013 planning period, to improve the effectiveness and sustainability of the cohesion policy. Two of them promote financial engineering instruments (JEREMIE and JESSICA), and the two others (JASPERS and JASMINE) are technical assistance mechanisms. They are currently being assessed and overhauled to better fit to local needs and capacities (new options for implementation, more flexible co-financing terms and complementary financial incentive resources). These instruments are now called Financial Instrument (FI).

3 Four joint initiatives were developed by the European Commission (Directorate-General for Regional Policy), in cooperation with the European Investment Bank Group and other financial institutions within the framework of the 2007-2013 planning period, to improve the effectiveness and sustainability of the cohesion policy. Two of them promote financial engineering instruments (JEREMIE and JESSICA), and the two others (JASPERS and JASMINE) are technical assistance mechanisms. They are currently being assessed and overhauled to better fit to local needs and capacities (new options for implementation, more flexible co-financing terms and complementary financial incentive resources).

4 In 2007, the Commission launched the JESSICA instrument with the goal of supporting sustainable and integrated urban renewal projects. It makes use of various financial tools, such as equity investments, loans and guarantees to create a favourable context for public and private reinvestment in urban infrastructure projects, with the desire to make up for market failures.

5 See detailed table of the 3 UDFs.

6 London Energy Efficiency Fund (LEEF): see detailed table of the UDFs.

7 The selection of projects was called into question even within the Greater London Authority by the environmental and health committee, which criticised the top-down approach of the projects and the absence of viable community projects developed by citizen organisations.