PAP 73 - Les Monédières, landscape and regional project

Laurence Renard, Régis Ambroise, Alain Freytet, Odile Marcel, February 2024

Le Collectif Paysages de l’Après-Pétrole (PAP)

One of the charms of the Millevaches plateau is its cover of moorland, meadows and peat bogs framed by deciduous and coniferous forests. On the horizon of these diverse landscapes are panoramas with distant views. To the south of this high granite country, the Monédières massif forms a bastion whose heather-covered puys also offer 360° views over the borders of Corrèze. Following the abandonment of farming in the 1960s, the plateau was planted with monocultures of Douglas fir and spruce. Today, these changes are being questioned by a number of initiatives that are renewing agricultural approaches and the way in which their economic activity can succeed in satisfying a variety of social needs as well as the requirement for sustainability.

To download : article-73-collectif-pap_lr.pdf (5 MiB)

Physical and historical data

The last foothill of the Millevaches plateau to the south-west, between Treignac and Egletons (Corrèze), the Monédières massif marks the watershed between the Vézère and Corrèze rivers. The Puy de la Monédière and the Suc au May, its main peaks, exceed 900m. Together with the six other puys, peuchs or sucs, the rounded shapes of these medium-sized mountains give a highly visible rhythm to the landscape, on the threshold of the plateau itself 1 . The Monédières massif is close to the heart of the Limousin people. It’s a place steeped in history where people come to walk, contemplate the landscape, pick blueberries and mushrooms, practise nature sports or watch their enthusiasts. There are many walking and hiking trails. Le Suc au May attracts almost 40,000 visitors every year. An orientation table gives the names of the peaks visible in the distance. The Monédières site inspired accordionist Jean Ségurel, who celebrated the landscape in his songs 2. Like the mountain passes of the Alps and Pyrenees, the Monédières massif has been a favourite venue for major cycling events such as the Tour de France and the Bol d’Or 3. Paragliding, which is recognised at a national level, is as much a feature of the skies as the birds themselves. The puy de la Grande Monédière is equipped for this activity.

The landscape of the Millevaches plateau has changed significantly over the last fifty years as a result of changes in the agricultural system 4. Before the Second World War, villages were built on flat land above the wet valley floors. Irrigated hay meadows surrounded them. On the slopes, terraces held back by low drystone walls were planted with food crops, on which manure from pig, sheep and cattle rearing was spread. The heather moors cover large open areas on the plateau, where trees are rare. Each farmer farms an average of 25 hectares. After the Second World War, land use changed with mechanisation and the introduction of inputs. Accessible to tractors, the flat areas previously given over to crops were replaced by hay meadows. This was replaced by ruminant farming from the 1960s onwards, due to low cereal yields. Abandoned land was planted with Douglas fir or abandoned. In the 1980s, the number of livestock increased and with it the need for fodder. The heather or callune, which had been preserved until then, was cleared on the gentler slopes. On steep slopes, the woodland continued to advance. The moorland and peat bogs were insufficient to feed the cattle. They have been abandoned and are becoming overgrown. Many dry stone walls are no longer maintained or are destroyed. Today, the area specialises in the birth of cattle sent to Italy for fattening. Most of the crops grown here are cattle feed (rye, wheat, triticale and maize). The wetlands have been relatively preserved, but only 1% of the plateau remains covered in moorland. A farmer generally has 120 head of cattle and farms an average of 250 hectares per worker. The result is an inverted landscape, a concept developed by Gilles Clément to describe the way in which agricultural abandonment ‘leads, in all regions with a pronounced relief, to the spontaneous afforestation of slopes where farm machinery cannot pass, and to the deforestation by reparcelling of flat areas’ 6. Comparing the demographic evolution of the Millevaches plateau and that of its wooded area, landscape architect Ninon Bonzom notes an inverse proportion between the presence of inhabitants and the omnipresence of plantations: ‘From the utopia of the peasant-reforester to the industrial enresinement, the inhabitants see their landscapes slipping away from them’ 7.

Today, encouraged by subsidies and the advice of forest managers to whom they delegate the management of their plots, landowners who are often strangers to the plateau are clear-cutting and replanting monocultures on their private plots. This is also the case on communal properties, despite the warnings issued by the local population since the 1970s. The landscape is not only a source of income, but also a living environment. Its confining effects have been observed on the inhabitants who remain, isolated in clearings in the middle of a sea of dark trees 8. In these areas of exile, with their difficult terrain and harsh climate, a policy of developing natural resources was put in place with the creation of a regional nature park in 2004, which now covers a large part of the Millevaches plateau. Fourteen of its sites are part of the European Natura 2000 network, including the Landes des Monédières site since 2007 9. Like the plateau as a whole, the Monédières Massif has been subject to forest encroachment as a result of land clearing and, above all, softwood plantations. On the summits of the massif, only two sites have retained their moorland landscape and therefore their visual openness: the panorama of the Landes des Monédières site thanks to the continued grazing by a family of farmers, the Deguillaume family, and the Fournaise balcony because of the need for space for hang-gliding take-offs. On the summit of Suc au May and the surrounding area, this approach to sheep grazing developed by the Monédières farm is the only way of perpetuating the heather moorland landscape that once covered 70% of the massif.

Landscape study to restore light and landscape

Concerned about the future of the massif in the face of emerging agricultural, forestry and tourism dynamics, the Millevaches Regional Nature Park commissioned a landscape study in 2017 which attempted to revive collective ownership of this remarkable landscape entity based on workshops bringing together numerous partners, elected representatives and local residents over a two-year period 10. Writing and mapping workshops, guided walks and an evening devoted to history and legends all served to illustrate the way in which the inhabitants of the massif lived and felt about their landscape.

As the figurehead of the Millevaches plateau, the Monédières massif forms a landmark. A small Limousin mountain, it is a kind of lighthouse in the landscape, a place whose exceptional views arouse the sacred impulse often associated with commanding views. The aim of the consultation meetings held during the study was to develop a shared vision for the site, on the basis of which a landscape enhancement project could be defined. The objectives were to restore and develop the moorland by managing the coniferous trees, to reopen the main views of the summit landscape, to reinforce or even create remarkable views, to enhance the small heritage, to organise the visitor reception areas and to complete the network of paths based on a general interpretation plan. The study provides a detailed description of the different landscape units and the woodland that affects the most outstanding views. It argues for the need to restore a larger area of heathland, particularly on the heights of the puys. The issues at stake are securing livestock farms, preserving the landscape’s openness to the horizon, maintaining threatened biodiversity on the scale of the Regional Nature Park, and encouraging gliding and paragliding. In order to make the most of the resources available in the area, and to avoid planting conifers, the landscape architects are recommending a change in farming practices. This change forms part of the management guidelines they are proposing. The geometric shape of the plantations, linked to the contingencies of the land parcels, blurs the coherence of the landscape. Their homogeneity encloses it, and the contrast between their colour and that of the natural environment darkens it. Recognition of the remarkable value of the Monédières massif naturally led to its inclusion on the list of sites to be classified under the 1930 law. At the initiative of the landscape architects, the site inspector from the DREAL Nouvelle Aquitaine presented the advantages of this classification so that these landscapes could be better recognised and protected. However, due to a lack of political support and, locally, a fear of regulations, the classification project did not come to fruition. In its report submitted to the Nouvelle-Aquitaine regional biodiversity agency, the nature park notes the lack of resources among local players to carry out the projects identified in the study and their difficulty in setting up multi-partner projects 11. Nevertheless, the park believes that various developments will be able to assert the landscape and environmental identity of the massif and enhance the reputation of the site.

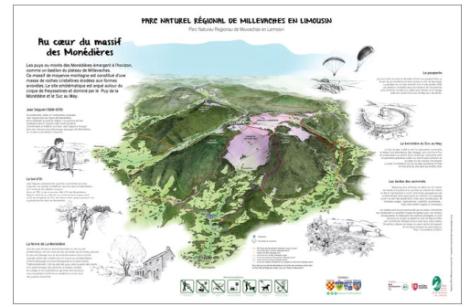

Routes have been signposted and educational panels installed at the initiative of the RNP, particularly at the top of Suc au May. On this panel, the drawing recreates the shape of the site. It depicts the surrounding villages and locates the footpaths that take you into the intimacy of the massif. The various motifs to be depicted were chosen during a consultation workshop: Jean Ségurel and his accordion, the Bol d’Or cyclists, the paragliders, the orientation table, the moor and its sheep, and the Deguillaume family farm, recognised by all as a place that should not be missed. The landscape designer’s panel focuses the eye and gives substance to a shared vision, a possible basis for a regional project that has yet to be brought to life and consolidated. Due to a lack of coordination between the various players, the coherence of the routes is still imperfect. A certain amount of disappointment has been expressed locally at the fact that, after the consensus reached at the coordination meetings, there has been a delay in implementing the guidelines set out in the study, and that some local authorities are still planting conifers on their land.

The study did, however, recognise the role of the Deguillaume family farm: ‘The Monédière farm is at the heart of the moor. Without it, the face of the Monédières would have lost its most remarkable feature, the heather. Thanks to their extensive knowledge of the area and their diversified practices, the farm is running smoothly and welcoming many visitors, who they help to inform about the local landscape and the ecological richness of the environment. The Deguillaume farm helps to maintain the heathland, the heart of the Monédières landscape, in the interests of the region and its sustainability.

The farm at La Monédière has belonged to the Deguillaume family for over a century. From the 1920s onwards, tenant farmers raised sheep and a few head of cattle. In 1976, Cédric’s father took over 120 hectares of fallow forage land, including 20 hectares of bilberry moorland. While his brother set about reforesting the land he had inherited, Cédric set up a herd of Limousin ewes and harvested wild bilberries. He set up a limited company to manage processing and marketing. His son Cédric took over the farm in 2009 with his wife Stéphanie. They set up a joint enterprise (GAEC) and joined the SARL to maintain an extensive farm of 250 Limousin ewes, almost entirely free-range, which produce meat and keep back the overgrowth threatening the bilberries. A sheepfold protects the lambs from bad weather and predators. Cédric buys a little hay in the region to feed the animals in winter, while the rest of the flock finds its food outside. To supplement their income, the couple are growing organic vegetables and red fruit on 0.6 hectares in three greenhouses. This business is expanding, while blueberry harvests are down due to drought in spring and summer, forcing the Deguillaume family to buy from outside. The couple offer snacks at the farm in summer and sell their produce direct all year round. Today, the farm employs two FTEs, a salaried employee three days a week and six to ten seasonal workers in July to harvest blueberries and welcome visitors to the farm.

The couple trained as landscape architects when they set up on the farm, taking a master’s degree at ENSP Versailles-Marseille. With their vocational baccalaureate in agriculture, Cedric and Stéphanie see the landscape as a resource to be managed in order to strengthen the farm’s autonomy. They therefore limit inputs by drawing fodder from each environment. This helps to maintain the open countryside, which was also a concern of Cédric Deguillaume’s father when he took over the farm. The landscape culture that drives the two farmers is also supported by various scientific and technical networks. In particular, they are in contact with researcher Nathan Morsel, who currently works as a farmer with the Plateau des Millevaches pastoral association. His principle is to adapt the management system to the vegetation in place and not the other way round 12. The diversity of natural environments on the plateau provides resources for feeding livestock, unlike today’s conventional livestock farming, which relies on inputs to produce the hay and cereals that feed the animals in their stalls, where they stay most of the time. The economic fragility of this type of farming encourages the development of pastoralism, with a detailed study of the mosaic of environments present on farms. In addition to grassland, cattle grazing includes grassland, undergrowth (including coniferous undergrowth), shrubby fallow land, peat bogs, moorland, etc. This means that these farms, which spend little on inputs, achieve economic equilibrium in areas that are not easily mechanised and are said to be ‘not very productive’. In the same way, the Monédières farm’s quest for sobriety tends to reduce its equipment requirements. To optimise passive energies - animal heat, heat from the greenhouse, movement of manure, etc. - architect Simon Teyssou has installed two greenhouses. The one that is a sheepfold in winter becomes a greenhouse in summer, with the manure left on the ground. Considered from an agricultural point of view as having a ‘natural handicap’, the Deguillaume farm achieves a respectable financial balance thanks to its constant search for ingenious systems to save effort and therefore energy.

Pastoralism keeps the landscape open, preserves the wild blueberry resource and provides fodder for the livestock. The farm has a wide variety of environments: callune moorland, broom grassland, fern meadows, wetlands, meadows, forest wasteland, bourdaine wasteland, etc. While his father had defined a limited number of parks where the ewes were free to roam, Cédric has finely broken down more than seventy areas according to the nature of the vegetation. He moves the ewes around almost daily, depending on the season.

The rigorous application of this management model preserves the Monédières landscape and its blueberry moors. Such a definition of the job is similar to that of an environmental manager, but also aims for a carefully considered profitability. This fine-tuned approach to the eco-landscape is based on the skills of the two farmers, who see the geographical environment as a resource from which man can derive his livelihood and whose potential must be preserved. « Grazing spontaneous vegetation saves on inputs and equipment. This thrifty agro-pastoral system, the fruit of adaptation to the environment, creates wealth and jobs’ 13.

He also recognises the landscape for its contemplative value: satisfied with the daily pleasure of moving his animals in such an environment, the farmer prefers the view of a south-facing slope with a very open panorama. Rekindling the cultural dimension of their professional practice, the two farmers meet the identity expectations of the local people, whose unique environment they have managed to preserve.

Landscape culture, an agricultural and social alternative?

Reclaiming the Limousin mountains for pastoralists is not on the agenda because of the dominant agricultural model’s lack of interest in these approaches and the weak position of local administrative institutions. Although there are questions about the ability of these new models to spread, the innovative approaches adopted by these farms are nonetheless developing conclusive experiments to manage the environment, feed the population and achieve virtuous sobriety. They could become benchmarks in the midst of this century’s turbulence and the intensity of its present and predicted crises. In fact, the sheer size of the massif’s sparsely populated areas and the diversity of initiatives experimenting with new ways of life offer a reserve of freedom to the surrounding urban areas, many of whom come and return to visit a massif preserved from the tourist densities that are building up elsewhere. Situated on the borders of the départements and communities of communes, the way in which this emblematic site is managed calls for a shared project that could ultimately give a new face and a new way of life to the whole massif. Placing the landscape and its resources at the heart of the farming system, they are opting for the multifunctionality of an activity whose productive objective remains closely associated with the values of respect for living things, both animal and plant, which also means care, social ties and shared beauty.

-

1 The name Monédières refers to the massif, the village, the farm, the puy and the stream. The origin of the name is a matter of debate. According to Chateaubriand, it could come from Mons Diei or Montes Diei, Monts de la Lumière or Monts de Jupiter, since they are lit all day long. Another explanation evokes the Sanskrit mountch and djara, the place where springs and streams are born. A final hypothesis combines Celtic and Roman origins, with dervos and montes meaning oak-covered mountains.

-

2 A ten-time millionaire record producer, Jean Ségurel is the author and composer of more than six hundred songs, the most famous of which, Bruyères corréziennes, a waltz created in 1936, expresses a personal vision of the particularly beautiful heather in bloom on the slopes of the Monédières. The song went round the world and is still one of the fifty greatest hits of French chanson: ‘Quand la bruyère est fleurie aux flancs des Monédières, ils sont loin les soucis pour les gens de Paris’ (the people of Correze who moved to the capital). Wikipedia, Monédières article.

-

3 Endurance race run, just after the Tour de France, around the village of Chaumeil from 1950 to 2002.

-

4 These transformations are studied in detail in Nathan Morsel’s thesis, Systèmes pastoraux économes pour moyenne montagne - IUFR Agriculture comparée AgroParisTech.

-

7 The rural exodus, which was very strong in the Limousin even before the First World War, has left its mark on individual and collective memories as well as on the landscape. Abandoned pastures, advancing forests, deserted villages, closed schools and services are recurring images. Little by little, the forests became privatised, escaping from the locals and enriching companies or individuals outside the territory. Between the nostalgia of a vanished rural world and the utopia of new arrivals, the inhabitants no longer really produce the landscapes they inhabit. Graduation diploma from the nature and landscape school in Blois: Habiter les versants de Faux-la-Montagne (2018), www.cahiers-ecole-de-blois.fr/tfe-ninon-bonzom/

An excerpt was posted on the alternative website www.journal-ipns.oles-articles/843-les-chiffres-qui-racontent-l-inversion-paysagere

-

8 Claire Labrue, L’enfermement de l’habitat par la forêt : exemples du plateau de Millevaches, des Maures et des Vosges du nord, doctoral thesis in geography, University of Limoges, 2009. Jean-Baptiste Vidalou, Être forêts. Habiter des territoires en lutte, La Découverte, Zones, 2017.

-

9 These sites are covered by an objectives document for which funding is provided. On site, they help to manage the natural environment of the moorland and prevent it from becoming overgrown. 244 ha of the Monédières moorland site: monedieres.n2000.fr/

-

10 The study was carried out by the landscape architects Lieux-Dits, Alain Freytet and Yoann Bit-Monnot.

-

11 www.biodiversite-nouvelle-aquitaine.fr/initiative/?id=88milieu monedieres.n2000.fr/

-

13 Presentation of Nathan Morsel’s thesis on the CNRS website www.prodig.cnrs.fr/nathan-morsel/