PAP 63: Trajectoire Zan

transforming our city outskirts into archipelagos

Bertrand Folléa, December 2022

Le Collectif Paysages de l’Après-Pétrole (PAP)

Anxious to ensure the energy transition and, more generally, the transition of our societies towards sustainable development, 60 planning professionals have joined together in an association to promote the central role that landscape approaches can play in regional planning policies. In this article, Bertrand Folléa, landscape and urban planner, Grand prix national du Paysage 2016, explains his point of view on « transition through landscape » in peripheral areas.

To download : article-63-collectif-pap_bf.pdf (18 MiB)

The only memory I have of my paternal grandfather is that he offered me a vile candy, of a strange black colour. He took it out of a small red and yellow tin from his pocket. Greedy, I started to suck on it. But the staggering build-up of minty liquorice taste soon made me run to the toilet to spit out the horror. I had tasted ZAN. Give me ZAN », « Taste ZAN », all advertising slogans from a bygone era. It is not certain that, taken up today in the techno language of urban planning, they would be enough to help elected officials swallow the bitter pill of contemporary ZAN: Zero Net Artificialisation 1.

For this new ZAN expresses a strong will against the irrepressible urban sprawl observed over the past seventy years. Region by region, it aims to reduce the rate of artificialisation of natural, agricultural and forest areas by 50% by 2030 compared to the consumption measured between 2011 and 2020, until reaching net zero in 2050. By this date, each hectare of artificial land should be compensated by a hectare of re-naturalized land.

Like two opposing tribes

This principle opposes two blocks, like two tribes fighting each other. On the one hand, there is the UI tribe, which includes urbanised areas and the infrastructures linked to them. - roads, car parks etc. On the other, the ENAF tribe, which in our laws includes natural, agricultural and forest areas. To describe the extension of the urban area, we note that the IUs colonise the ENAF and artificially alter the surfaces by a sort of scorched earth policy. In ten minutes, when you have finished reading this, the IUs will have conquered 12,000 m2 of ENAF, the equivalent of 2.5 football pitches. So we mobilise a super referee, ZAN, to step in and settle the matter by 2050, aiming for a draw. But is the situation so binary? If we are talking about soil - and not just land - and substrate - and not just surface area - the opposition between IUs and NAEs does not hold: for the past seventy years, soil has been degraded by urbanisation as well as by agriculture and even forestry. Urban sprawl sterilises it; so does intensive agriculture, by reducing it to a support cleaned by pesticides and nourished by the spreading of fertilisers from the chemical industry; and intensive forestry acidifies it through monospecific stands of conifers 2. In its dual horizontal (space, land) and vertical (substrate) sense, the soil is sterilised by both IUs and NFU. Faced with this situation, the meaning of public action is to preserve, recreate or seek everywhere the conditions of a fertile soil. By sterilising our soils, by artificialising the landscape, our living environment, the great system that holds together urbanisation, infrastructures, agriculture, forests and natural areas is being disrupted. Countless examples of these dysfunctions show the close interweaving of IUs and ENAFs in our planning practices: the degradation of town entrances; the devitalization of town centres; the banalization of inhabited or worked spaces - in the form of standardized housing estates or business parks spread out by the kilometre -; the dependence on the private car and the truck; the eradication of hedges and trees due to reparcelling or their loss of economic value; the turning over of meadows; the extension of industrial-scale monocultures; soil erosion through runoff; the abnormally destructive and even deadly nature of floods; junk food; soil, water and air pollution; the rarefaction of birds, insects and fish; and recently, climate disruption, which has resulted in global warming as well as extreme events (droughts, heat waves, fires, etc.) and health crises. ) and health crises. We are living in an artificial sub-system that is problematic, costly to maintain and in reality unsustainable.

Changing energy

What is our system-landscape ill with? A dependence on a hard drug, not very visible as such, but massively consumed by IUs and NESTs for decades: fossil and non-renewable energy. Oil, coal, gas and uranium are legal substances of fantastic power, efficiency and convenience. We consume them in astronomical quantities3. It is these inordinate volumes that have created all of these imbalances. No urban sprawl - with the resulting devitalization of urban and village centres - without the massive use of oil that makes it possible to live far from one’s place of work and services. There can be no intensive agriculture without huge consumption of gas to produce the inputs. No climate change without burning huge quantities of coal, which emits greenhouse gases. Fewer wars without our pathological dependence on fossil fuels, which are becoming increasingly scarce, straining international relations, making conflicts abnormally long and causing massive destruction.

Everything is connected. It has to be said openly, even if it sounds like a caricature: fossil fuel is the cause of the upheaval of our landscape-system. There is an overarching reason for our problems; and this is perhaps good news, because by tackling this cause, many of these difficulties will be overcome. The political objectives are clear: energy transition is the mother of all battles.

Changing the landscape

The landscape is at the heart of this challenge because it is at the crossroads of the sectoral fields of planning which are all concerned by the energy, ecological, societal and economic transition to which they must contribute. For each player, making the transition a reality means making a contribution to a common goal: that of shaping not only a liveable environment, but a desirable post-oil landscape. For we must transform our living environment - the functioning of our physical environment, including the great cycle in which soils play a key ecosystemic role - but also our lifestyles. We need to change our relationship to energy in quality and quantity, and therefore our relationship to space and time, i.e. change our sensitive relationship to the world, the very definition of landscape. In other words: change the landscape.

Another urbanism

In contrast to the trends followed or initiated by urban planning over the last seventy years, the revelation of soils and landscapes as matrices of development constitutes a breakthrough urbanism that we call the landscape approach 4. This approach opens up a renewed territorial narrative. Attention to the landscape in fact gives rise to an urbanism that is hollow and inverted by ceasing to consider unbuilt space as a void to be urbanised and, on the contrary, by showing it as full of space, horizon, life, production, carbon storage, uses, exchanges and relations with its context. It may be necessary to urbanise this space, but perhaps not, or not completely: it depends on the landscape project that we are aiming for, on the relationships that we want to establish between the urbanised, the urbanisable and the non-urbanisable. In an urban landscape plan, the unbuilt is what is drawn first, in colour. Attention to the ground, on the other hand, generates an urbanism from below and as if reversed, where the underside will explain, account for and authorise the overside. It is therefore important to lift the buildings, houses, car parks, business buildings, squares, fields, vineyards and forests to look at what is underneath. To show soils, their nature and diversity; to explain their precise organisation; to explain how they function in the cycle of life; to reveal their importance for the trophic chain, agro-ecology, water, air (gas exchange and carbon storage, denitrification), landscapes, and all the ecosystem services they provide when in good condition.

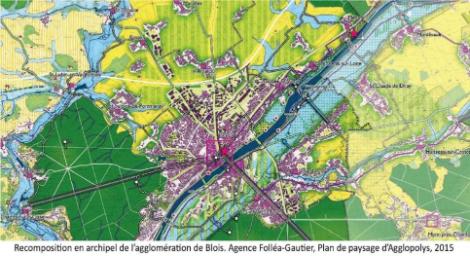

The figure of the archipelago

What form does this new kind of urbanism, inverted and reversed, give rise to? What does the landscape of transition look like? For thirty years, the figure of transitional urbanism has been the archipelago for me. The sea is the metaphorical figure and the primary element. When applied to land planning, this continuity can be, depending on the geography of the place: a sea of vines, an ocean of wheat, a forest horizon, an expanse of pastures or lakes, a river arm, etc. It has a thickness, depths and volume, precisely those of our soil-substrate. It is not a void, it is the nourishing and vital sea, protected as a strategic resource. The sea is also what connects and brings people together; it is through it that we circulate. It is therefore home to travel infrastructures. It is also the area without human habitation, which hosts a few islands of structures or industrial equipment at risk requiring isolation, for example a factory. The sea is therefore not the only domain of the ENAF, the IUs also have their place there, very precisely defined. The islands that dot the food chain represent towns and villages. The agricultural, natural and forested sea separates them and guarantees their identification and integrity. Urbanisation does not draw continents, the dimensions and forms it takes are controlled so that proximity to the sea is a sensitive reality and not an abstraction. Nor does it extend into peninsulas: no linear village-streets transformed into town-roads laid end to end. Just as the sea is not the sole domain of ENAF, islands are not the exclusive domain of IUs. ENAFs have a right to be there because the sea penetrates through arms, it is found in the interior in small spaces or linear parks, gardens, green corridors, squares and shaded streets.

The third component of our archipelago is the shores, which play a crucial role. Between the sea and the islands, there is not the « nothing » of the abstract line separating the U or AU zone from the A or N zone on an urban planning document. The shores of our towns and villages have long been made up of orchards, gardens and vegetable patches, market gardens: places of intensive and skilful production, as close as possible to the consumer areas. The layout was finely organised. Today, these spaces must become those of contemporary urban or peri-urban agriculture, but also of interface facilities such as rainwater management basins, wastewater treatment plants, renewable energy production units, local sports and leisure areas, walking and play parks, all of which must be hybridised to avoid the syndrome of a single-function facility closed in on itself. This space of connection and exchange is as important in the visible horizontal world as the ground is in the invisible vertical world.

The archipelago territory is thus the figure of the landscape of transition. The relations between the IUs and the ENAFs are established in a single metabolic and cyclical system in three dimensions: two constitute the surfaces in length and width, the third is the thickness of the critical zone 5.

Soils and landscapes are less valuable than buildings, houses or business buildings, less visible than a festival hall or a stadium. But soils and landscapes are invaluable in terms of ecosystem and metabolic services, as well as in terms of attractiveness and physical and psychological well-being for humans. Such functions are particularly crucial in this period of ecological transition, when it is important to transform our living environments and lifestyles so that they become sober, decarbonised, resilient, lively and desirable. They are common goods. As keys to the transition, we can collectively place them above particular and sectoral interests. We still need to know them, recognise them and value them so that they form the basis of the city, the territories and the living environments in transition.

ZAN and archipelago

Let’s go back to our urban planning bonanza. The ZAN objective proposed by the law does not act on the entire archipelago landscape since it does not consider agricultural spaces as being able to enter the equation of desartificialisation, neither as an objective nor as a means. Other acronyms and regulations will have to be invented to bring crops into an agro-sylvo-ecology that regenerates soils and unbuilt environments. Because of this restriction in the use of the concepts of artificialisation and soil, ZAN misses the opportunity to have a tool for the renaturation of landscapes as a whole, articulating the UI and the ENAF in the synthetic aim of an archipelago.

ZAN and centres

If ZAN abandons the great sea of the ENAF to its chop, how will it act on the island towns and villages of the IUs and their shores? To accommodate the need for housing, activities and facilities, urbanised land will be required to transform itself in an increasingly imperative manner as there is little space to be de-artificialised to compensate for the extensions. Not all this land is made of the same concrete. It is easy to distinguish between dense, compact pre-oil urban fabrics and those impregnated with fossil energy, which are more distended. The former are the city centres, villages and old suburbs. The latter, built over the last seventy years, are the vast areas of housing estates, business parks, roads and car parks known as the « ugly France ». Let us not dream of the hyperdensification of this first category. Almost all of them inherited from the urban structures of the pre-oil era, the town and village centres are land-saving. There is no need to upset this often heritage built heritage in the name of imperative densification, but rather to engage in the reclamation of the cohort of vacant dwellings (nearly three million in town centres in France) and empty shops by surgical adaptations of a delicate urban and architectural fabric that is not always adapted to contemporary needs. Rather than seeing their « hollow spaces » and wastelands systematically filled in, these old city centres need to have landscape and ecological continuities woven into them by means of promenades and pedestrian and cycle paths, as well as green and blue screens offering nature in close proximity to the inhabitants and making it possible to temper the heat waves by refreshing plantations. This renewed wealth of nature will make the density of the centres attractive and desirable once again. This restoration of urban and village nature will undoubtedly have to be weighed up against desartificialisation in order to encourage it. Without having waited for ZAN, urban planning documents are already working on this by introducing coefficients for open spaces, canopies and vegetation, and through dedicated development and programming guidelines (OAP). The reflections resulting from the Action Coeur de Ville and Small Towns of Tomorrow schemes often lead to the paradox that the intensification of town centres and their renewed attractiveness require their de-densification and renaturation.

Net zero

What does ZAN add to the tools already available? The 2030 objective aims to halve the rate of artificialisation in less than ten years. It raises questions about the definition of terms, the instruments for measuring artificialisation and the scale of its application, but at least it is clear, and therefore an incentive. What about Net Zero by 2050? This is where the problem lies. The Zero Net objective slams home and has the effect of a masked vigilante signing with the point of his sword: less heroic, the Net appears quite ambiguous. In the wake of the ERC doctrine (avoid, reduce, compensate), the introduction of a compensation principle raises various problems. Why would re-naturation give the right to build on the other hand? Making it a bargaining chip opens the door to so many alibi projects, which will become increasingly absurd as this currency becomes scarcer. Why should we renaturalise in Creuse when we artificialise in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques (or vice versa), on the pretext that these two departments are located in the same region, governed by the same SRADDET? Such purely accounting logic has no chance of guaranteeing a quality landscape for either the Creusois or the Basques. The same reasoning applies to the scale of a SCOT or a PLUi. And how will this compensation take place? Who will pay for the renaturation? Will the developer buy the right to build on agricultural land in municipality A (as Artifice) and pay for the renaturation of land in municipality R? Will municipality Z plant trees on its lawns and in its urban vistas in order to claim a right to urbanise this or that cow pasture as a result of this renaturation? In the feverish land market, urban, peri-urban or industrial wasteland will then tend to become the speculative value par excellence, amassed by the cleverest (developers, banks, insurance companies, you, me…) because it is universally coveted either to be urbanised without encumbering the right to artificialise, or renaturated in order to open up rights to artificialise, or to accommodate photovoltaic panels that we have not been able to put on roofs. And in the end, it is so expensive that nothing will be done with it. In reality, it is the landscape project, specific to a given place and its character, with its sensitive dimension linked to uses and perceptions, which must define the happy marriages between UI and ENAF and the desirable balance between artificialization and renaturation; with, to guide them, objectives of proportions posted in the urban planning documents and coefficients as mentioned above. This has nothing to do with a doctrine of compensation whose inefficiency in terms of biodiversity and agricultural land has been noted for decades. In other words, and to sum up: proportions yes, offsets no.

ZAN and the urbanisation of oil

In this logic of landscape project, how can we try to orientate ZAN in the best possible way since it is written into the law? ZAN should not be aimed primarily at historic town centres and villages, but should concentrate on the second category of IUs, the peripheries that are spread out all around them, those immense areas built up in favour of the oil industry in vast monofunctional zones that are only mixed on the scale of the car. It is in this generalised emulsion of recent diffuse urbanisation that we must concentrate our efforts to reinvent urban landscapes as an archipelago, i.e. decanted by a clearer division between vocations that are either more urban or more natural, and sewn to their agri-natural context by so many edges composed like shores. The scope for such action is immense, on these still adolescent surfaces - without a well-defined personality - where the balance between artificialisation and renaturation will have to find its point of balance on a project scale.

ZAZA

In these immense oil peripheries, the expansion of which must be slowed down, we must above all stop the headlong rush of commercial surfaces, a field in which France is the world champion. Our country has built as much retail space in the last twenty years as in the previous forty. The ZAN sets a clear and ambitious objective of reducing the rate of artificialisation by 50% by 2030, but without distinguishing between housing and activity - particularly commercial activity - while the latter is still largely dominated by the western conquest syndrome. The Climate and Resilience Act, from which ZAN is derived, has set the threshold for the prohibition of artificialising commercial floor space at 10,000m2, but 90% of shoebox commercial buildings are smaller. The team is not pulling in the same direction to slow down this race to the bottom, which is being maintained by both retailers and local authorities in their mutual competition. A much more effective brake is needed to limit the number of ZAs, calling for delicate work to renew our existing diffuse peripheries and, at the same time, our devitalized centralities: a ZAZA, if we like acronyms, for zero artificialization by activity zones, especially commercial ones.

5P

To remedy the shortcomings of the distended urbanisation of oil, it is important to combine two opposing and complementary principles. These spaces must be artificialised, intensified and ‘urbanised’ by creating secondary urban centres, relocating services, shops and jobs, gradually increasing the height of residential buildings, densifying business parks, providing active and shared mobility and public transport, and creating urban edges with the neighbouring agricultural and natural areas that will continue to exist. On the other hand, they must be de-artificialized by preserving islands of natural heritage or landscape identified as interesting 6, but also by deconstructing oversized buildings or neighbourhoods located in high-risk areas, and by reclaiming breathing spaces, urbanisation breaks, and ecological continuities combining public spaces, green and blue networks, soft traffic and perspectives 7. This combination of artificialisation and renaturation can only be harmonious within the framework of a 5P (post-oil peri-urban landscape plan), which will draw in the same project the landscape grid of the surfaces to be reclaimed - the constitutive framework of the landscape to be recomposed -, and those points of urban intensification to be planned.

Archipelagising our peripheries

A small part of the peripheral urbanisation is being remodelled as a result of the policy that the ANRU is carrying out in the most vulnerable neighbourhoods with social difficulties. However, huge areas of housing estates, business parks and linear urbanisations remain under the radar of public urban planning policies, not being part of any operation labelled ANRU, PVD, ACV, PNRQAD or PIA. This is where the ZAN trajectory must land. We must remodel our peripheries to transform them into archipelagos combining centralities and new types of natural spaces, all of which are alive and fertile. We must therefore initiate real projects to reclaim the landscape of diffuse urbanisation by recycling urbanised oil landscapes into sober, decarbonised and resilient urban landscapes. ZAN, as we have understood, will not be enough for such a Marshall Plan. Its compensation logic borders on mystification. It will be necessary, well beyond that, to reverse a tax system that currently favours urban sprawl 8. And just as water has its own water agencies, human and financial resources must be deployed for the common good of the land and the landscapes to be reconstructed. Finally, beyond ZAN, we must not forget the sea of ENAF that farmers criss-cross, so that it regains its fertility and can also accommodate the few islands of IU for risky reindustrialisation or highly harmful activities.

-

1 Following the publication of the application decrees of 29 April 2022, the Association of Mayors of France filed an appeal with the Council of State on 22 June against two application decrees.

-

2 The phenomenon of the artificialization of forests is not massive in France because it is slowed down by the extreme fragmentation of private land, which is largely kept unmanaged.

-

3 In « L’Imagier Paysage et Energie », published by the Landscape and Energy Chair in September 2022, I propose consumption figures by relating them to the person or to the second to have orders of magnitude that are easier to perceive. This image book is accessible on the Internet from this page: presse.ademe.fr/2022/09/levolution-des-paysages-en-france-dhier-a-2050-quelle-place-pour-lenergie.html

-

4 Read in particular « L’Archipel des métamorphoses - la transition par le paysage », Bertrand Folléa, éditions Parenthèses, 2019. See also the proceedings of the 2021 Biscarrosse seminar of the APCE (Association des paysagistes-conseils de l’Etat) published in September 2022, the Appeal to Good Government co-signed by PAP, APCE, FFP, FNCAUE, FPNRF, FNAU, RGSF in March 2022.

-

5 According to OZCAR-IR (Critical Zone Observatories, Applications and Research), the Critical Zone is the outermost film of the planet Earth, the one that is the seat of chemical interactions between air, water and rocks. It is a porous medium resulting from the transformation of minerals in contact with oxygen, CO2 and water on the Earth’s surface. It is the seat of life and the habitat of the human species. It is therefore critical in a physical sense because it is one of the interfaces of the planet, but also because it is where we cultivate the land, where water and soil resources are formed and evolve, and where we store our waste.

-

6 ZAN makes this possible by distinguishing between artificial and non-artificial spaces in the same U-zone. This makes it possible to avoid indiscriminate and abusive densification to the detriment of a recognised landscape and nature heritage (park, garden, heart of a block, etc.). On the other hand, in decree no. 2022-763 of 29 April 2022, the classification of grassy areas (lawns, meadows or grasslands) as artificial spaces may have the perverse effect of inviting them to be planted with trees in order to be considered as renatured spaces, which does not necessarily make sense, particularly in an urban environment where open spaces can be valuable in terms of views and breathing space, as well as environments for biodiversity

-

7 Parks, urban agriculture, sports and leisure areas, urban nature reserves, and the hybridisations that can take place there.

-

8 Property tax on buildings, the territorial economic contribution (CET), for example.

Sources

To go further

B. Folléa : L’Archipel des Métamorphoses – la transition par le paysage, Editions Parenthèses (mai 2019) (French)