PAP 59 : towards a sustainable management of our landscapes? The difficult example of a Catalan vineyard

Soazig Darnay, June 2022

Le Collectif Paysages de l’Après-Pétrole (PAP)

Anxious to ensure the energy transition and, more generally, the transition of our societies towards sustainable development, 60 planning professionals have joined together in an association to promote the central role that landscape approaches can play in regional planning policies. In this article, Soazig Darnay, landscape architect, addresses the issue of sustainable landscape management policy through the example of a Catalan vineyard.

To download : article-59-collectif-pap_sd-.pdf (9.3 MiB)

A landscape policy

Our countryside and its landscapes were profoundly transformed during the second half of the 20th century. In the context of Reconstruction, the Common Agricultural Policy aimed to ensure the continent’s food autonomy. To achieve this, it promoted a productivist model from the 1960s onwards. Denounced as early as the 1980s 1, the industrial dynamic that was gradually imposed led to the trivialisation 2 of certain territories and their landscapes. Sociologist Pierre Sansot 3 believes that the need to name the landscape arises when the identity of a territory is disrupted by an accelerated transformation of what surrounds us. The loss of identity gives rise to a feeling of deterritorialisation 4. In reaction to this phenomenon, the notion of landscape has been asserted in France within public policies through a variety of actions, and in particular the 1993 law 5. In the continuity of a reflection on spatial planning and on the right of citizens to a quality environment, the European Landscape Convention signed in 2000 proposes that democratic tools be adopted for the protection, management and planning of territories. Harmonising the different approaches thanks to a methodology common to the European countries, landscape units and values will be described and objectives will be deduced from them. Landscape plans and landscape charters combining social, environmental and heritage dimensions will be adopted. Landscape can be used to integrate the various policies that aim to animate and strengthen the identity and activities of a given territory. European countries are invited to undertake landscape approaches to ensure the harmonious development of their territories.

Landscape policy in Spanish Catalonia

After the fall of the dictatorship in 1975, Spain’s entry into the European Economic Community (1986) deconstructed the traditional agricultural balance by initiating a specialisation of crops often unsuited to the Mediterranean ecosystem 6. This transformation was carried out by the large landowners rather than by the terroirs still managed by family structures. The frenzy of financial and real estate speculation has disfigured Mediterranean villages and coastlines, especially from 1994 to 2008, while agricultural diversity has faded.

Catalonia quickly identified that the European Landscape Convention could allow it to claim its particular identity. As a frontier between the Christian and Muslim worlds in the Middle Ages, the Catalan nation established a Mediterranean trading empire early on. Its subsequent development made the province a dynamic and prosperous enclave, whose capital was marked by the « golden fever » (1876-1886) and the urbanism of the modernist era. The autonomous region therefore joined the European Landscape Convention in 2005 7. It created a Landscape Observatory in Olot, 20,000 inhabitants, a pre-Pyrenean village known for its landscape paintings from the second half of the 19th century. The affirmation of the Catalan landscape identity is based on references to the mountains, the sea and an imaginative modernism.

What recognition for the agricultural landscape?

The status of agricultural areas and their landscapes is still uncertain. In 1995, the General Territorial Plan of Catalonia highlighted the scarcity of land with slopes of less than 20%, and thus the inevitable competition between urban development and areas devoted to agriculture. The latest territorial planning tools, the partial territorial plans, could consolidate this recognition by incorporating the work of the Landscape Observatory and its landscape quality objectives. However, this recognition is not general and the whole Catalan territory is still not covered. In Catalonia, as in most European countries, the implementation of the convention is gradual and the concept of landscape is slow to become a coherent basis for the various policies. Catalan territorial planning is carried out by urban planners: the Landscape Observatory currently depends on the department in charge of this planning. On the other hand, a Nature Agency in charge of the management of natural spaces - mainly private - was created in 2020, without any link with the Observatory.

At the same time, the Department of Agriculture has drafted a law promoting the protection of agricultural soils 8. This law recognises the productive value of the soil, but the landscape quality is not mentioned. For their part, the provinces and their governments, the diputaciones, are developing other planning logics. As relays for central government policies throughout the country, the provinces are well-funded administrations. They have not contributed to promoting landscape policies in Catalonia that comply with the European Convention, which Spain adopted later. In Catalonia, the diputaciones still manage the natural parks in a spirit of conserving the natural heritage. For its part, the diputación of Barcelona has developed since the 1990s a green belt inspired by the London greenbelt, which includes natural parks and has allowed the creation of some agricultural and rural parks. Most of these parks are peri-urban spaces subject to significant pressures. However, they are not clearly claimed as landscapes or as terroirs. More recently, since the signing of the Milan Pact 9 by Barcelona, declarations in favour of the city’s food sovereignty and the development of agro-ecology have suggested the possibility of strengthening the links between the city and these productive spaces. However, commercial exchanges are struggling to take place 10. The landscape integration to which the European convention invites is therefore underway, but not yet explicitly achieved.

Heritage landscape or productive space?

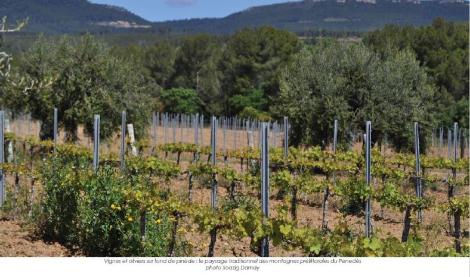

Are ordinary agricultural areas not recognised as landscapes? The catalogues drawn up by the Landscape Observatory include the work of local associations that testify to their value for the population. Similarly, the leisure practices and comments of urban dwellers are inspired by an attachment to the countryside that is often associated with a romantic and nostalgic imagination, as described in the work of sociologist Bertrand Hervieu. Here, as in France, we often speak of the farmer as landscape gardener. The sociologist points out that there is a contradiction between the expectations of citizens who love a traditional landscape that is disappearing and the reality of modern farming. This contradiction is particularly evident in the case of terraced farming, traditionally structured by dry stone walls. Numerous local associations list the smallest low walls that are now hidden in the forests. The Landscape Observatory relays this information in its descriptive maps. The dry stone heritage is recognised as world heritage by UNESCO. However, it is rare that their protection is provided for in communal urban planning documents. In an agricultural context, these elements tend to disappear and with them the profile of the slopes and the composition of the corresponding plots, that is to say, the whole of the ecosystems with both heritage and ecological value. The maintenance of these ecosystems is crucial to the management of water run-off, which can destroy soils and cause flooding in the Mediterranean climate, as well as the survival of areas of refuge for biodiversity and, more generally, the landscape identity itself. In the Penedès region, the largest Catalan vineyard in terms of surface area and production volume, it is more difficult to obtain financial aid for the maintenance or reconstruction of dry stone walls than for joining and levelling neighbouring plots. Nevertheless, the local wine sector has a close link with the notion of landscape, which it does not hesitate to promote in a discourse on terroir. In Penedès, in reaction to a project to install a waste treatment plant, the entire winegrowing profession joined forces with the local authorities in 2003 to request the drafting of a first landscape charter, anticipating the landscape law that introduced them in Catalonia in 2005.

The landscape and the European Landscape Convention were seen as tools to be mobilised to protect the quality of the territories. From that moment on, this terroir has constantly promoted wine tourism in order to demonstrate the economic profitability of these landscapes and to raise awareness of their conservation. The traditional wine-growing landscapes of the Penedès are not recognised as exceptional, but the landscape charter of the Alt Penedès region, together with the recognition of tourism, have made it possible to demonstrate their interest. Before Covid, the Penedès was for many years the second most important wine tourism destination in Spain 11. However, do these development tools help to define a virtuous landscape and maintain an idealised landscape of identity?

Wine tourism, a tool to conserve the landscape?

In the Penedès, the three wineries that receive more than three quarters of the tourists are international-scale properties. Much of their production is organised to drive down prices. The resulting production model does not defend a system with high environmental value or respect for the landscape. Other owners, a minority in terms of surface area, defend the transparency and quality of their production. Comparable to the French independent winegrowers, they combine the quality of the terroir, the quality of the landscape and an ecological or even biodynamic production 12. They are opposed to the fragmentation of the vineyard under the urban pressure of the metropolis, and invest in the restoration of dry stone walls near the accesses to the property. On the other hand, they do not hesitate to destroy certain low walls in areas that are nevertheless appreciated for the beauty of their landscape, to cut back woodland along streams or plot boundaries, and to construct buildings for tourist purposes without always thinking about their integration. Some wineries manage their surroundings with care but do not look kindly on the passage of walkers through the plots. It is true that vandalism and theft have increased as the number of visitors has increased.

The logic that would have us believe that the quality of these landscapes should be maintained by the winegrowers and the cellars thanks to the profitability of wine tourism activities is therefore to be qualified. Furthermore, is the definition of a quality landscape the same for the local resident who goes for a walk, for the foreign tourist, for the winegrower, the artisanal cellar or the large wine merchant? In relation to different expectations, are identity referents perceived and shared by all? Are they strategic elements to be protected? How to define and maintain their authenticity? Not all the players in the wine sector are interested in developing wine tourism, which they do not always want to do or have the capacity to do, particularly because of the delicate management of the nuisance caused by the passage of walkers. During the summer season, the multiplication of bar services within the wineries raises various difficulties - parking, light pollution or noise - which are difficult to manage by understaffed rural services and in the absence of standards. On the other hand, rural tourism does not constitute a systematic economic support for the vineyards. In the Penedès, it is not uncommon for rural accommodation to be used by Catalan or Spanish city dwellers who do not plan to visit the wineries, preferring the swimming pool or a barbecue with friends: they will drink Rioja, the wine of another region.

The landscape is the result of an economic reality Based on artisanal processing, local recognition and consumption of a product, and support from tourism activities, the sustainable development model is not clearly applied by all. In the case of the Amazonian forests and the maintenance of their natural ecosystems, Xavier-Arnaud de Sartre 13 highlighted that the growth of the ecotourism offer does not allow this model alone to support a virtuous circle, as the volume of potential customers does not follow the same trend. Rather, it would be the recognition of ecosystem services 14 and their integration into the economy that would enable the safeguarding of these environments. As far as they are concerned, European agricultural areas and their landscapes are primarily aimed at profitability linked to their exploitation. Wine is one of the products of agricultural transformation that generates the highest economic margin, and it attracts and has attracted many investors in very different regions and countries. In France, Spain and Italy, its economic weight in national exports gives it a particular status. Is the wine-producing landscape therefore a landscape capable of maintaining itself more easily than an agricultural landscape with less income? Studies have in fact demonstrated its capacity to resist urban pressure in a metropolitan environment 15. The fact remains that small isolated or sloping vineyards are becoming rare in vineyards with little international recognition, despite the beauty of the resulting landscapes. In all cases, it is a question of being able to balance the cost of maintenance with the selling price of the wine 16. The unpredictability of weather and health conditions linked to climate change, and the increasing pressure of wild fauna do not help to maintain isolated plots in a complex landscape mosaic. In addition, labour is becoming scarce and the population of farmers is ageing. In Spain, there are no structures to limit the effect of retirements and land speculation, as in France, the chambers of agriculture and the SAFERs.

Before the Penedès became a dense vine-growing area, since the 18th century, large areas of cereals traditionally occupied the bottom of the plain, with fruit trees. The landscape has been simplified into a monoculture of vines under the influence of the CAP and an economic structure dominated by a powerful wine trade. The simplification continues despite the growing demand for more varied local food production. When we talk about the need to preserve the Penedès winegrowing landscape, are we talking about a traditional landscape made up of varied and diversified farming units, a landscape that has now disappeared, or about a modern, monocultured vineyard that has difficulty in meeting environmental challenges? Today’s dominant economy encourages the development of a vineyard stripped of its heritage dimension, but concerned with a certain ecological balance, and developing renewable energy production services in the form of fields of solar panels surrounded by fences, an effect of land speculation in the metropolitan environment.

Externalities to be valued?

What externalities should be valued in order to encourage a more sustainable and complex agricultural landscape model, capable of preserving a heritage identity? Agriculture is recognised as having the capacity to store carbon, encouraged by the agro-forestry model, but the wood value chain is little developed in Catalonia. Due to the lack of water, the choice of fruit trees is also limited. In the case of the Penedès, there are other externalities, such as its metropolitan location, which makes it a natural choice as a leisure area. At present, the majority of cultivated areas are not offered for tourism. When private owners decide to invest in this direction, the picnic areas and lookouts can be abused by some walkers, which creates tensions with the local population. Other externalities are the many private woods that are not maintained because they cannot be used. Most of these are pine forests that cover the prelittoral mountains with their steep rocky slopes. Traditional mushroom or wild asparagus harvesting, walks: these woods are very popular. The risk of fire has increased considerably in recent years. The possibility of reintroducing cultivated plots, including vines, is being questioned. Some of these plots, which are about to be abandoned, still exist in the massifs and could be maintained if their role as firebreaks were recognised. In this case, livestock farming would be a necessary complement, especially as flocks of sheep have already been reintroduced to graze in the vineyards during the vegetative rest period. A vineyard will only be an effective firebreak if it is positioned according to the slopes and the habitat. On the other hand, maintaining a vegetation cover between the rows of vines would be favourable to biodiversity and erosion control, but favourable to fires. What priority should be given to one or other of these externalities? Similarly, what balance should be struck between support for externalities and concern for productivity, the primary purpose of agriculture and livestock farming? The model of sustainable development and the bioeconomy that takes externalities into account define the maintenance of these landscapes from an anthropocentric analysis in which the economic equilibrium of the enterprise must be maintained within the capitalist system. If we recognise the need for a paradigm shift to take into consideration the whole that links human and natural interests, the political Gaia defended by Bruno Latour, this analysis will have to abandon the priority given to profit and take as its primary objective the sustainability of the system, its value as a common good for all living things. We can then talk about agricultural landscapes, from an anthropocentric point of view, while favouring an aesthetic dimension where the heritage part of the landscape will be conceived in an ecosystemic way. This conception of a prosperous and sustainable landscape could undoubtedly become a lever for the involvement of the population. In his film Vignes dans le rouge (2021), the filmmaker Christophe Fauchère shows us a divided sector. Initiatives inspired by permaculture and agroforestry seek to respect the deep nature of the land, like the vine, a climbing plant that clings to the branches of trees. On the other hand, industrial innovations are preoccupied with creating new, more resistant varieties, and continue to enlarge the plots. How long will our landscape be divided between these two worlds, one governed by technological logic, the other inspired by natural dynamics? One thing is certain: the appearance of winegrowing landscapes will evolve, no doubt moving away from a conservative heritage aesthetic. This evolution will create new, more diverse and better composed landscapes. The term « living landscape » will take on its full meaning here, especially as the living will not be sacrificed.

-

1 The collection Mort du paysage ?, Edition Champ Vallon, was published in 1982.

-

2 In the last chapter of his Histoire du paysage français, published by Tallandier (1983), Jean Robert Pitte questions this trivialisation of landscape. He would later become a fervent defender of the gastronomic terroir.

-

3 Pierre Sansot, « Pour une esthétique des paysages ordinaires », Ethnologie française, t.19, n°3, Crise du paysage ?, p. 239-245.

-

5 Law nº 93-24 of 8 January 1993 on the protection and enhancement of landscapes. For a history of public landscape policies, see Alexis Pernet’s Le grand paysage en projet - Histoire, critique et expérience, Metis Presse, 2014.

-

6 Robert Savé, former director of the Catalan Agricultural Research Institute, denounces the fragility of non-irrigated Mediterranean agriculture and the absurdity of certain irrigation strategies. Cf. the report by the Triptolemos Foundation that he co-authored: « Informe sobre el impacto del Pacto Verde desde un enfoque de sistema alimentario Global » www.triptolemos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/INFORMETRIPTOLEMOS- IMPACTO-GREEN-DEAL.pdf

-

7 Law 8/2005 on the protection, management and planning of the landscape.

-

8 Law 3/2019, of 17 June, on agricultural areas. The decree allowing its development still does not exist.

-

9 Launched at the 2015 World Expo in Milan, this pact is based on three main commitments: to preserve agricultural land, to favour local circuits and not to waste food.

-

10 Work by Patricia Homs, ethnologist, Universitat de Barcelona.

-

11 Reports by the Association of Spanish Wine Cities ACEVIN on the use of wine routes. The Penedès Cava route is the second most popular in Spain until 2019, behind the Sherry route.

-

12 At the beginning of 2022, steps are being taken in Catalonia to have different categories of wine producers recognised and to distinguish between merchants, cooperatives and wineries that produce their own grapes on the labels.

-

13 « From common goods to ecosystem services: change of discourse or change of speaker? » / Xavier Arnauld de Sartre, in seminar « Penser les biens communs dans le espaces ruraux: regards croisés », organised by the « Dynamiques rurales » laboratory of the University of Toulouse II-Le Mirail with the support of doctoral students and students of the master’s degree « Développement des territoires ruraux » and of the TESC Doctoral School (Temps, Espaces, Sociétés, Cultures), University of Toulouse II-Le Mirail, 11-12 March 2013

-

14 This notion emerged in the 1970s with the observation that the processes that act within a natural ecosystem provide free services to the human societies that depend on it.

-

15 For example, Stéphanie Pérès’ thesis in economics: « La vigne et la ville: forme urbaine et usage des sols » (2007, University of Bordeaux).

-

16 In the Penedès, artisanal wineries consider that the price of wine sold to the public should reach 40€ per bottle in order to maintain the dry stone terraces on the hillsides. Although some are known for selling high quality wines, the designation of origin does not currently generate the demand necessary to sell large volumes at this price. The winery’s ability to maintain the terraces is therefore limited by its sales network and its ability to sell its premium wine.