Housing for people with mental illness

A problem too little taken into account in housing policies

Pascale Thys, 2012

The problem of people suffering from mental illness is complex. Complex because we have few reference points to understand and act towards these people, complex because their difficulties generate many problems in their daily lives. Among these, we are interested in the question of housing. Indeed, many social workers say they are powerless in the face of the significant increase in the number of mentally ill people who have housing problems, or even who find themselves on the street. We will attempt to review some of the field observations that have been made, as well as possible solutions for policies that take greater account of these citizens « like the others ».

Small definition of the phenomenon of mental illness and its scope1

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as « a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the ordinary stresses of life, and is able to contribute to his or her community ". According to the WHO, more than one in four people have or will have a mental disorder in their lifetime (lifetime prevalence) and about one in ten have or will have a mental illness at some time (point prevalence).

These disorders have diagnostic classifications based on criteria and targeted therapeutic actions. Not only are there several classification grids, but they also evolve over time, which makes trend analyses difficult. For example, the DSM-IV provides clear descriptions of diagnostic categories. The WHO lists five mental illnesses among the ten most worrying pathologies for the 21st century:

-

schizophrenia,

-

bipolar disorder,

-

addiction,

-

depression

-

and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

According to specialists, there is an urgent need for action because estimates indicate that the number of people suffering from mental illness will increase significantly in the coming years, with a 50% increase in the contribution of mental illnesses to the burden of disease by 2020. The situation of the younger generations seems to be particularly worrying.

Our work (at Habitat and Participation in Belgium2) has led us to consider that this phenomenon has an enormous impact on the countries of the North (Europe - United States of America), resulting in an upsurge in poor housing and homelessness directly linked to mental health problems. These are both the cause and the effect of poor housing in our countries.

Housing problems: mutually reinforcing factors

-

The refusal of psychiatric hospitals to continue to accommodate on a long-term basis people in mental suffering who are not in crisis, both for reasons of budgetary reduction, but also because it is not necessarily a long-term solution for these people. Some talk about putting the « crazies back in the city. »

-

The fact of living in conditions of extreme precariousness, or even of being on the street, creates imbalances (physical, spatial and social references, etc.) which lead to mental health problems for the people who are subjected to them.

-

Social workers are not trained doctors and do not necessarily identify the mental health problem that the person they are accompanying may have. They therefore propose housing situations that do not take into account the problems of crisis, dual diagnosis, denial, etc.

-

Finally, it is clear that the mentally ill, even if mild, are scary. If he declares himself as such to a landlord, the latter is likely to refuse him access to housing. People in difficulty will therefore hide their problems or their mental suffering and, in the event of difficulties, the landlord will end up with non-payment of rent or an indefinite departure without understanding the cause of the phenomenon. This will be the occasion to break the lease or to put the person in great difficulty to find his housing. The neighborhood, unaware of the problem, can reinforce the owner’s choice. FEANTSA3 adds a fifth factor to these four factors that we observed during our work:

-

The increase of domestic violence, creating phenomena of mental disorders for those who suffer them (mainly women).

As we can well understand, bad housing, or even the absence of housing is both a cause and a consequence of the phenomena of mental suffering of people. This is also shown by a study recently carried out in Barcelona by Joan Uribe Vilarrodona4. He showed that there is a direct link between homelessness and the quality and number of hours of sleep, mental disorders (stress, anxiety and fear) as well as chronic neurological and musculoskeletal diseases. He reminds us that homeless people tend to seek medical help only in times of crisis, which limits the continuity of treatment.

A conceptual framework to better situate the debate : the missing link5

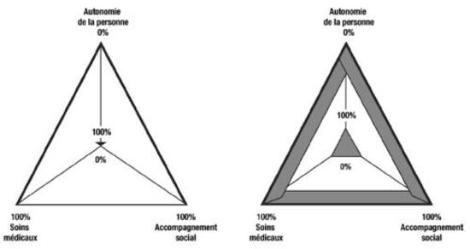

The following diagram will allow us to position the debate when talking about housing for people with mental illness. The lower the degree of autonomy, the greater the need for medical care and social support, hence the three angles of our triangle. For example, a person with 0% autonomy will probably need 100% medical care and 100% (social) support.

Pascale Thys, 2012

The second diagram shows what medical and social workers identify in the field. According to them, there is on the one hand a fringe of people with very serious difficulties who access the various assistance services and, on the other, a fringe of the population whose problems require little help whatsoever. In the end, the population that is difficult to care for today is the one that falls between these two « extremes »: people can live independently, but will need - at one time or another - a real and important medical and social support.

These are the people who will experience cyclical problems of poor housing. These are the people for whom systems should be put in place so that help is available at the right time (and not continuously).

These people, left to their own devices, who will also be found on our streets, experience a double exclusion :

-

the one linked to their mental health problem,

-

reinforced by that linked to the criminalization of poverty and the stigmatization of a passage to the street.

The situation of young people is also to be underlined here: many young people who suffer from psychological ill-being, or even mental suffering (which does not imply that there is « mental illness ") will either find themselves in wandering situations, or in « light » housing or squats.

The shortcomings of the current systems

Within the framework of our work (INTERREG IV), Belgian and French medico-social workers agreed to identify the following gaps in their respective social frameworks

-

Relatively autonomous people often do not have access to the minimum health care and social support to housing that they need because they are considered « too » autonomous !

-

The notion of continuity in services is lacking. We have noted shortcomings in terms of housing that would allow people to remain in them when their condition improves. Too many facilities are transitional and any move is experienced as an additional source of stress.

-

When people have a significant degree of autonomy, what they are looking for is not temporary housing, but a place to stay, to live, to anchor themselves in a fulfilling environment… But with a device that can be activated in times of crisis.

A list of recommendations for the political world6.

In its review, FEANTSA explains European progress in dealing with these issues. « In the field of mental health, following a consultation in 2006, a European Pact on Mental Health and Well-being was launched in June 2008 by the European Commission, the Slovenian Presidency and the WHO European Regional Office. While recognizing the challenges ahead, the Pact calls for a (voluntary) partnership for action in five priority areas, one of which is related to stigma and discrimination. The signatories commit themselves to contribute to the implementation of the Pact through the exchange of information, the identification of examples of good practice and the development of recommendations and action plans. Thematic conferences have been organized to disseminate relevant results and to raise awareness of the different aspects involved, while a Mental Health Compass for action on mental health and well-being has been created to make useful information available online}7« .

Our work led us to formulate a series of very concrete recommendations presented to local and regional leaders in our respective countries at the end of 2010. These tracks were co-developed, within the framework of these INTERREG IV meetings, with social workers, medical workers as well as associations of families of people in mental suffering (UNAFAM and SIMILES).

1. A secure, long-term framework in adaptable housing

Obtaining this support for people suffering from mental illness can take various forms. The working group selected three of them :

-

identify a medico-social referent known to the person and callable in case of need ;

-

giving priority - even temporarily - to « collective housing » solutions ;

-

limit as much as possible the moves, source of great stress.

To be effective, these people must be supported over the long term !

2-Opening up to the outside world

Develop « mixed » habitats, i.e., where everyone could meet, including people with mental health problems, in a non-stigmatizing manner. It is important to offer activities to these people, activities that get them « out » of the secure structures. It is also important that the neighborhood be made aware of the potential problems of these people, so that they can help them when necessary rather than reject them in a crisis.

3-Sustainable, Customized Living

Establish a continuity of housing « offers » for people in mental distress. We must avoid the famous « missing link » by creating bridges between services. Living à la carte also means being able to stay in housing for a long period of time, with social supervision that persists over time because, in all likelihood, the person will sooner or later need this external assistance. Offering both individual and collective housing in the same building has been very successful.

4-Networking and partnerships

Beyond the definitions of these terms, and even their instrumentalization, it is interesting to note the great desire on the part of those involved to work in networks. By this they mean a network of professionals, in which the family can play a role, which functions with certain codes (such as shared secrecy) and which aims to find innovative solutions where an individual, sectorial approach is lacking in solution.

5-Family and caregivers at the heart of the system

Families and caregivers often have the impression that they are excluded from the support system. SIMILES and UNAFAM, associations of parents and friends of people suffering from mental illness, have developed the concept of « citizen psychiatry » which consists of allowing non-professionals to receive sufficient training to be able to intervene when necessary. And why not imagine accommodations where families could be welcomed for a free and temporary stay, allowing them to immerse themselves in the therapeutic path of their loved one and to be trained in « citizen psychiatry ».

1 INTERREG IV work of meetings between Belgian and French social workers since 2004 and carrying out social support in housing for people in difficulty. Conclusions of the INTERREG 2011 work on social support in housing for people in mental distress.

3 Work within the « mental health » group 2010-2012 at Habitat and Participation (families and relatives of people in mental suffering who are trying to set up collective housing formulas).

4 Joan Uribe Vilarrodona (juribe@ohsjd.es) is director of St. John of God Social Services (Source = FEANTSA magazine 2011).

5 FEANTSA Magazine Spring 2011 : health of homeless people : breaking through barriers.

6 See our INTERREG IV work.

7 FEANTSA Magazine Spring 2011 : Health and homelessness : A holistic approach.

Sources

BIBLIOGRAPHY

-

INTERREG IV work of meetings between Belgian and French social workers since 2004 and carrying out social support in housing for people in difficulty.

-

Conclusions of the INTERREG 2011 work on social support in housing for people in mental distress.

-

Work within the « mental health » group 2010-2012 at Habitat et Participation (families and relatives of people in mental distress who try to set up collective housing formulas).

-

FEANTSA Magazine Spring 2011 : Health of Homeless People : Breaking the Barriers

-

« Psychological suffering of adolescents and young adults ", working group in 2000 convened by the Ministry of Employment and Solidarity - High Committee for Public Health.

SITOGRAPHY

-

FEANTSA website [a(http://www.feantsa.org/fr)

-

Website of l’UNAFAM

-

Website of SIMILES

-

Website of the European Union on Mental Health

To go further

To view the PDF of issue 7 of the Gateway series