Feedback from the Twize Program in Mauritania

Nouakchott and Nouadhibou, MAURITANIA

Aurore MANSION, Christophe HENNART, Virginie RACHMUHL, 2014

Centre Sud - Situations Urbaines de Développement

This fact sheet presents feedback on projects to rehabilitate slum areas in Mauritania.

Acting through projects to build the city? Feedback on the Twize program experience

The Twize housing improvement program was implemented by GRET, a French international solidarity and development NGO, in two major cities in Mauritania.

Drawing on the experience of previous projects conducted by GRET in Brazil (Fortaleza) and Cameroon (Fourmi), the program aimed to test an integrated urban approach by working on four inputs :

-

access to low-cost housing that is close to existing practices among the Moorish population

-

the establishment of a housing financing system combining initial contributions from families, credit and subsidies, as well as the parallel offer of credit for economic activities,

-

vocational training

-

the development of community facilities and infrastructures in the intervention areas.

Launched as a pilot project in 1998 under the supervision of the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights, Poverty Reduction and Integration (CDHLCPI), a cross-cutting agency reporting to the Mauritanian Prime Minister, the program underwent a significant change in scale when it was integrated into the Urban Development Program (UDP) in 2002, a program co-financed by the World Bank and the Mauritanian government.

Closed in 2008, the program lasted 10 years with a total budget of 13 million euros. It was part of a policy to eradicate informal settlements and « modernize » Mauritanian cities. It targeted first-time homeowners with a land title, living in under-equipped housing estates.

The financial package combined a 60% subsidy from the State, 10% direct contribution from the inhabitants, and 30% through a solidarity credit system involving groups of 5 to 10 families. Individual credit was also experimented with. A microfinance institution « Beit El Mal » was created. At the end of 2008, it had 19,000 active clients, more than 70% of whom were women, and 1.3 million euros in outstanding loans.

The program aimed at a double efficiency: to ensure a sustained rhythm of construction in response to the quantitative objectives defined by the PDU (construction of 250-300 « modules » per month in the last period) and a good quality/price ratio of the proposed housing products while securing the financial circuit.

The project has made it possible to build 5,900 modules, benefiting 30-35,000 people, costing between 2,000 and 2,500 euros, which are gradually being transformed by the reappropriation of the inhabitants.

The program has also trained 1,200 professionals (mainly in the construction sector, but also in other craft activities such as dyeing, couscous making, hairdressing, etc.) and carried out 95 community projects (in the areas of waste management, health, education, environment, early childhood, etc.). These activities have generated the establishment of a support center for the professional integration of young people and a plastic recycling program by women’s cooperatives.

The most promising innovations have been the mechanisms and tools for financing and producing affordable housing for poor families in Mauritania. The satisfaction rate of the inhabitants with the product offered is high. A certain form of reappropriation and institutionalization by the Mauritanian State on these aspects is underway, with limited possibility for GRET to contribute to institutional and organizational choices.

Advantages and limits of a pilot operation to restructure a precarious neighborhood

The desire to renew practices

In Mauritania, the Urban Development Program (UDP), with a budget of $100 million over ten years, was launched in 2001 and co-financed by the World Bank and the Mauritanian government. Its objectives combined the economic revitalization of the city, the improvement of living conditions and housing in the slum areas and the strengthening of the legal and institutional frameworks of the urban and land sectors.

The strategy adopted combined the Mauritanian government’s desire to « modernize the city » and to « put an end to the precarious neighborhoods » based on the World Bank’s operational guidelines for « involuntary resettlement of people », which are based on minimizing displacements and compensating displaced persons, regardless of their occupation status.

GRET, an international solidarity and development NGO, accompanied the Resettlement Unit of the Urban Development Agency (ADU) of Nouakchott, responsible for the implementation of operations in Nouakchott, from 2004-2006.

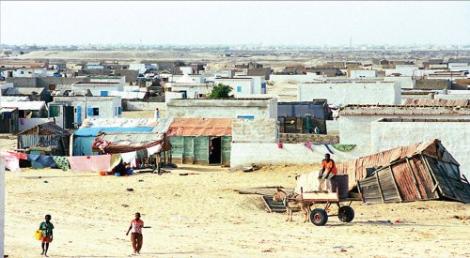

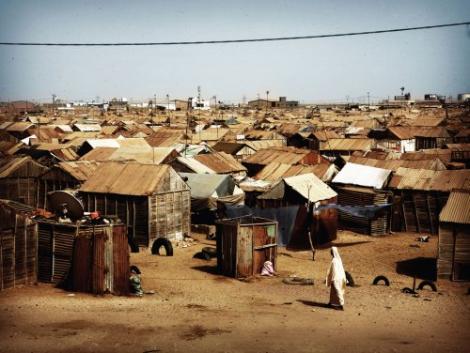

The El Mina kebbe was the first neighborhood chosen to test these new principles of action. The most populous neighborhood in Nouakchott-51,000 inhabitants and 14,300 households-near the center and the last kebbe in the city, it was home to the poorest people and was considered to be in political opposition.

The operation provided for the complete reorganization of the neighborhood, with the opening and development of streets, the installation of water and electricity services and social and commercial public facilities, as well as the regularization of land ownership for the inhabitants. A lump-sum compensation of 200 euros (equivalent to a little less than four times the local « SMIC ") was paid to all displaced rights holders. To prevent speculation and to secure the rights, the beneficiaries received a badge, in principle non-transferable for three years, which then gave them the right to obtain an occupation permit. The operation took place in two phases, between 2001 and 2008. The first phase, called « development », consisted of opening the main roads and clearing the right-of-way for the future public facilities. The second phase, called « reparcelling », reorganized the space within the « squares » drawn during the previous phase from an orthogonal subdivision plan. In total, approximately 7,000 households were relocated, 2,000 during the servicing phase in a neighboring neighborhood and 5,000 in relocation zones that are still being developed two kilometers from the initial site. The number of plots allocated has doubled compared to initial estimates.

A mixed record

The failure to control population displacement can be understood as the product of a set of trade-offs, including strategies for maximizing benefits by the inhabitants, the option of a « reorganization-reorganization » rather than a « reorganization-adjustment ", the complacency of the Mauritanian state in managing the allocations in order to maintain social peace, the desire to satisfy its clientele, formal compliance with the conditions and recommendations of the World Bank, and the electoral and financial gains anticipated by the communal elected officials, who were not very involved.

The experiment partially fulfilled its promises. It took place in relative social tranquility and largely benefited - which represents a real success for the Mauritanian actors - the inhabitants of poor or modest condition. Very quickly, we were able to observe a dynamic of development of the allocated plots of land, in the form of « hard » housing, individual latrines or fences with, for some, the support of a program for the improvement of popular housing called Twize and for economic development. Obtaining a free plot of land did not only generate a material benefit, but also a symbolic result, allowing them to finally feel like full citizens.

Nevertheless, the limitations of this operation-especially those arising from the high number of trips-are significant. Socio-urban inequalities have been reinforced by the rise in land and property prices in the original neighborhood, the under-equipment and the lower value of the relocation areas. The operation has contributed to urban sprawl without taking into account the cost and possible arrangements for supplying the new neighborhoods with infrastructure. The future management of these neighborhoods by the communes concerned was not anticipated. In terms of land security, the transition from the badge to the occupancy permit has not been carried out as planned, which makes the most vulnerable people vulnerable.

Finally, no system for recovering the costs and added value of the land has been put in place. The involvement of the international community limits the immediate impact on the Mauritanian government. What will happen when the cost of these operations must be borne by the State, while other precarious neighborhoods are to be treated in a similar manner?

Sources

Proceedings of the A-SUD Days: Precarious Habitats, Vulnerabilities and Public Policies, ENSAPLV, June 23, 2010, « Social housing production as an alternative - Acting through projects to build the city ? Feedback on the experience of the Twize program in Mauritania ". Virginie Rachmuhl, Christophe Hennart and Armelle Choplin.

S. ALLOU, A. CHOPLIN, C. HENNARD, C. RACHMUHL, L’habitat, un levier de réduction de la pauvreté. Analysis of the Twize program in Mauritania. GRET, Studies and works, issue 32, 2012.

« Future of precarious neighborhoods, future of the city : a linked destiny ? The example of Nouakchott, Mauritania » in Voyage en Afrique Urbaine, ed. Pierre Gras, l’Harmattan, Paris, 2009.