EcoBUDGET: recounting the environment differently

Tubigon (Philippines)/Växjö (Sweden)

2012

Fonds mondial pour le développement des villes (FMDV)

Two cities, Tubigon in the Philippines, with 41,600 inhabitants, and Växjö in Sweden, with 83,000 inhabitants – both on opposite sides of the world – are exploring the opportunities offered by the same tool: EcoBUDGET, a systematic environmental management tool created by ICLEI – local governments for sustainability Network in early 90’s.

Two contexts, two ways of thinking and acting based on a common concern to enhance the environmental capital, and sustainably preserve it, by integrating its contribution to the collective wealth into the budget: on the one hand in Tubigon, in an environment of poverty and vulnerability, which are closely linked, and on the other hand, in Växjö, in a quest for sustainable performance. Or when cooperation between cities, on two completely different sides of the world, gives rise to the commitment to integrated sustainability, as “what is not recounted ends up not counting any more”.

To download : cities_environment_creating_sustainable_wealth3.pdf (3.8 MiB)

Social inequalities, ecological inequalities: bridging the divide of a double jeopardy

Tubigon in the Philippines, with 41,600 inhabitants, is exploring the opportunities offered by the same instrument: EcoBUDGET, a systemic environmental management tool created at the beginning of the 90’s by ICLEI- Local governments for Sustainability.

Tubigon (41,600 inhabitants for 81 km2), a municipality in Bohol Province in the Philippines divided into 34 Barangays (decentralised units, each headed by a leader) manages a 2012/13 budget of roughly EUR 2.2m. The average monthly per capita income stands at roughly EUR 188.

The viability of its economy mainly relies on activities related to exploiting available natural resources (fishing, agriculture, livestock raising, wood, tourism…) on which the population is largely dependent. However, this ecological capital faces a number of threats (soil erosion, water pollution, forest cover loss…), which directly affect the living conditions of the poorest and their ability to make a sustainable livelihood from it.

Against this background, in 2005 the municipality adopted the EcoBUDGET framework instrument designed by the ICLEI network which, as a system to manage local natural resource consumption, is able to inform the city’s strategies and objectives for its development. The aim is to reduce the vulnerability of a section of the population and improve both their standard of living and access to basic urban services. By defining the impact of existing public environmental initiatives, this “environmental budget” facilitates monitoring and evaluation (qualitative and quantitative indicators) and, especially, ensures that these initiatives are integrated into the city’s annual budget.

Two examples of the direct impacts of the implementation of this environmental management system (EMS) can be mentioned: the mangroves (marine marshland ecosystem), an essential resource for the resilience of local natural environments, and therefore of communities, have been protected against intensive exploitation. Similarly, drinking water resources, the poor quality of which was becoming harmful to residents, have improved markedly.

EcoBUDGET, how it works

Through EcoBUDGET, the environment is perceived as a capital to be not only preserved, but especially, and to achieve this, to be enhanced. The tool identifies environmental problems (for example, poor water quality) and the resources involved (in this case, drinking water) for which the introduction of indicators (percentage of contaminated sources) will allow to monitor the resources improvement.

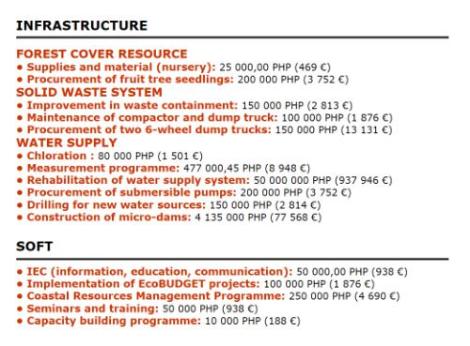

Action plans are defined to improve the quality of natural resources (monitoring of water sources, construction of dams…) and are allocated an annual budget. Environmental resources are not directly translated into monetary value: it is the projects resulting from the diagnostics and appraisals, conducted thanks to the indicators, which are ultimately included in the annual budgets of the relevant departments.

The EcoBUDGET cycle includes 5 phases:

-

The City of Tubigon takes stock of the 6 resources (drinking water, irrigation water, forest cover, fruit trees, coral reef and the built environment) selected to be included in the Master Budget, the name given to the environmental accounting system. This investigative phase first assesses the quality and availability of resources and, second, the ability of stakeholders to implement the actions required to preserve them.

-

During the preparation period, the Master Budget assigns physical and social indicators to each resource that will be subject to a specific action plan.

-

The objectives are defined for the short or medium term (2 and 5 years) and are subsequently discussed and approved by the City Council. The Council defines priorities, integrating the city’s development strategy via its 3-year executive and legislative programme and its annual investment plan.

-

The implementation of the Master Budget is then concretised via a series of actions, which are determined according to their impact not only on the preservation of resources, but also on the communities which rely on them.

-

A monitoring-evaluation compares the progress made by the programme with the identified objectives and allows the budget to be readjusted accordingly from year to year.

from FMDV, 2012

A three-pronged local renewal movement: pooling objectives, implementing instruments, adjusting the focus

EcoBUDGET’s integrative approach is conducive to an institutional arrangement that fosters ownership of environmental issues by both the political authorities and the technical departments in charge of the proposed measures (agriculture, pumping stations, urban planning and development). The action plans are adopted by the City Council, meaning these commitments are brought to the highest decision-making level.

The Technical Working Group (TWG), the programme’s technical backbone comprising 9 technicians from the municipality and the directors of the relevant departments, prepares, implements, and evaluates the Master Budget. In doing so, it maintains a continuous and horizontal dialogue between stakeholders. The preparation phase leads to a discussion at the City Development Council, the decision-making entity which gathers elected officials, technicians, NGOs, and other civil society representatives. Once it has been adopted, the Master Budget is made public and disseminated via the local newspaper.

For its part, the Poverty Database Monitoring System (PDMS), established under the Development Resources and Access to Municipal Services (DReAMS) programme supported by the European Union, was adopted in 2010 by the Bohol Province Urban Planning and Development Department and the Bohol Local Development Foundation. This database, comprising 19 indicators (malnutrition and infant mortality, diseases, electricity, waste system, housing, water, sanitation, unemployment…), identifies the levels of deprivation and subsequently determines the sectors requiring priority poverty reduction measures.

The TWG has therefore used the PDMS to assess the poverty status of the communities targeted by the environmental Master Budget. Combining these two decision-making instruments, the innovative coordination and interoperability of the diagnostics and of the programmes to be implemented as a result, provides both the authorities and local stakeholders with a multidimensional “relief” picture of the realities at work in the city area. They can thereby refine, for the future, the vision of the resilient development of the community and the corresponding choices.

This is how the action plan on drinking water resources, directly related to the fight against infant mortality, has succeeded in reducing the proportion of households without access to drinking water (9.68% in 2011 against 12.15% in 2007).

Tubigon’s local authorities eventually aim to directly integrate the EcoBUDGET indicators into the PDMS database in order to more clearly establish the correlation between natural resource protection and poverty reduction, thereby adopting a “dual target and impact” approach to its policy for strategic operations.

The symbolic story of an upturn in living conditions

Environmental protection is today a priority for Tubigon’s development agenda.

This success, linked to the formalisation, integration, and appropriation of the environmental management process, lies in its ability to establish a systemic link between a strategic vision of the city, urban development choices, the allocation of resources, the measurement of their performance, and the fight against poverty.

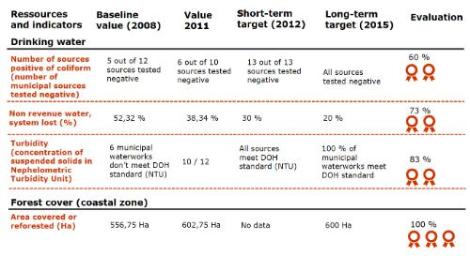

Consequently, the 2012 Master Budget shows that the municipality has achieved most of its short-term objectives, demonstrating that it is well on track for the medium and long term.

For example, the number of de-polluted sources rose from 5 in 2008 to 6 in 2011 and the percentage of illegal withdrawals fell from 52.32% in 2008 to 38.34% in 2011. Concerning irrigation water, 16 diversion dams have now been built against 7 in 2008. Irrigated farmland area has grown from 245 ha in 2008 to 361 ha in 2011, leading to an 11% productivity increase per hectare. In terms of the preservation of marine habitat, the creation of 10 protection zones has allowed coral cover to return to 50%. The waste collection system has seen its volume of solid waste fall to 60% of household waste with 80% of households now recycling. Beyond the state of natural resources, the EcoBUDGET action plans have thus made a significant improvement to residents’ living conditions. For instance, the 2012 PDMS shows that the portion of households suffering from malnutrition fell from 24.72% in 2007 to 13.58% in 2011 and that the percentage of households below the poverty line decreased from 40.45% to 29.05% over the same period.

EcoBUDGET, a key to a culture of cooperation

Local government commitment to the development of its city is crucial to the success of any EMS, which requires a strong vision that can guarantee investments over the long term. To this end, the creation of the TWG and the integration of EcoBUDGET into the relevant departments’ working plans have greatly facilitated its effective and lasting implementation. The commitment of local organisations throughout the process has also been instrumental to the integration of this process over time.

Although the municipality already had a culture of partnership with local stakeholders and civil society, the adoption of the EcoBUDGET has transformed this culture into a local management tool – a real circle of enhanced cooperation. For example, the TWG is today working directly with the volunteer community replanting trees in the mangroves and this is being done with the financial and technical support of the department in charge of this component. This volunteer participation is of major benefit to the municipality and guarantees the required ownership of the city’s resilience project by residents. The challenge for the municipality of Tubigon in its integrated approach lies in striking a balance between environmental protection measures, which are spread out over a long time span, and poverty reduction measures, which must be implemented in the shorter term. A social contract with residents thus makes it possible to offer them alternative economic opportunities to compensate for the consequences of the ban on exploiting newly protected resources. Training in fishing and equipment is therefore offered to residents who have notably been deprived of intensively exploiting the mangroves.

from FMDV, 2012

The municipality uses local and international partnerships for the allocation of the funds required and capacity building for new techniques. However, it was initially technical cooperation developed with the city of Växjö in Sweden that allowed the authorities to replicate EcoBUDGET in a municipality with a lower investment capacity, which demonstrates its adaptability.

Many challenges still remain

Since 2006, EcoBUDGET has clearly proved its worth in Tubigon where it has allowed the entire community to lastingly rewrite its history, with its own vocabulary, hence the locally supported interest that we see today in extending it further to other resources.

Financing for actions implemented to achieve the objectives approved in the Master Budget today account for between 10 and 15% of the municipality’s total expenditure. Each department involved must prepare its budget, including the additional cost of activities related to EcoBUDGET, which benefits from priority financing from the municipality. Additional funds are also allocated to certain costly projects, such as dam constructions, and certain programmes receive support from local and international NGOs.

Consequently, the funds invested in the EcoBUDGET programme rose from EUR 4,220 in 2006 to over EUR 1m in 2011 (EUR 1,054,390 for projects and EUR 8,630 for administration).

However, while the volume of financing dedicated to environmental resources has increased considerably, the municipality does not have the funds required to plan larger-scale actions or to expand preservation to other resources. In addition, this limitation concerns the lack of skills in the municipality to monitor and evaluate certain indicators. The same also holds true for measures on air quality, which cannot be introduced due to the lack of sufficiently qualified staff.

The formation of the environmental budget also comes up against the scope of the municipality’s legal competence (implementation of its action plan with regard to certain resources). During the first year of implementation of EcoBUDGET, the municipality had included extraction materials from quarries as a resource to be preserved. However, it did not manage to influence the protection of these areas, which falls within the competence of national government.

from FMDV, 2012

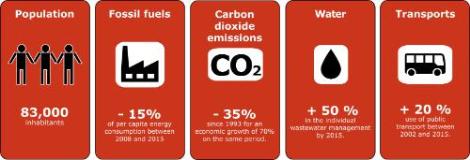

Växjö : The greenperformance

In 2003, Växjö adopted EcoBUDGET[[EcoBUDGET, developed by the ICLEI sustainable cities network, is a management system for local natural resource consumption, translated in the form of a budget voted by the City Council and integrated into the municipality’s general budget or forming a budget in itself parallel to the traditional budget.]], as an instrument to catalyse and monitor its environmental programme with the stated ambition of becoming the “greenest city in Europe”.

A tale of success.

Green accounting, a key to international outreach?

Växjö, a partner of a number of international projects, actively communicates on its green ambition.

This massive investment in territorial marketing has allowed it to innovate in several areas (new green technologies, lower energy consumption…). This was the case with EcoBUDGET, which today has been fully appropriated and which, by the power of its green accounting “story telling”, has helped it to pool local energies and attract international recognition and financing. The technical cooperation initiated with Tubigon in 2005 (exchange of practices on EcoBUDGET) reflects this ability to have “green outreach” beyond its borders.

A tool to share the green ambition

Växjö’s environmental management system is made up of two types of so-called “monitoring” and “budget” indicators. Only the budget indicators are integrated into EcoBUDGET (lack of statistical data in the city for the monitoring indicators, the objectives of which are, however, set out as priorities in the budget. Other objectives concern environmental resources, which are considered as measurable and can therefore be subject to annual budgeting).

The municipality has ten budget indicators for this purpose (e.g. the proportion of organic food consumption and the number of public transport journeys per person), included in the “traditional” annual budget during its preparatory phase. However, in this case it concerns items for which the environmental resources are assessed. Together they form a single document approved each year by the City Council. Each department is responsible for the objectives to be achieved via budget indicators and must integrate them into its action plan and annual budget. Every 6 months, the administration reports on the environmental budget to the City Council, which assesses the results shown by the indicators in the light of the stated objectives and makes the appropriate decisions in terms of readjusting or strengthening the policy. Thus, through this accounting process, the decision-making tool gives full visibility to the economic and social impacts of the environmental policy determined by the local authority. Moreover, the municipality is currently moving towards further integration of EcoBUDGET, whereby financial and environmental objectives are reflected in budget discussions.

Environmental resources, a factor still difficult to “recount”

However, Växjö’s experience illustrates the difficulties in creating indicators that are sufficiently relevant in order to accurately reflect the impacts of the environmental initiatives implemented by the municipality (appreciable translation of the improvements that can be directly linked to the projects implemented, technical teams able to make the relevant measurements to produce reliable statistics on which to base arguments for the recommended actions).

Consequently, the municipality preferred to reduce its number of budget indicators by selecting those for which it has sufficient measurement capacity (annual statistics) and for which it can control the trends.

In this case, practice shows the complications involved in wanting to “count the environment” in order to subsequently “recount” it better and provide support to politicians and citizens for the definition of the city’s strategic objectives, with regard to the challenges of preserving and rationally exploiting resources. The indicators selected are sometimes not sufficient to calculate the existing economic benefit from an investment to reduce CO2 emissions or the increase in green spaces, which is why Växjö sought to add an “income” column to its environmental budget. The purpose was to compare the cost of renovating a house to make it more energy efficient to the money saved on energy expenditure. This column was deleted as it was too complicated to fill in (difficulty to assess the added value generated by certain environmental initiatives). In this sense, the city’s next forward-looking approaches should be closely followed. EcoBUDGET may not be the only guide for the strong environmental strategy implemented in Växjö, but it has demonstrated that it is a powerful awareness-raising and communication tool for the municipal team for environmental issues. Indeed, it ensures that the related challenges are clearly identified and taken on board by the city’s elected officials and civil servants.

The visibility given to the EcoBUDGET approach, by placing it at the centre of the budgetary and financial debate, promises strong political consensus and greater collaboration between decision-makers and technicians to the cities which adopt a similar environmental management system. This can open a new chapter in the alliance between environmental sustainability and its consequences: economic and social benefits.

from FMDV, 2012

Sources

Tubigon

-

EcoBUDGET Guide for Asian Local Authorities, ICLEI, 2006.

-

EcoBUDGET: introduction for Mayors and Minicipal Councillors, 2007. Présentation powerpoint.

-

The EcoBUDGET guide: methods and procedures of an environmental management system for local authorities, ICLEI, 2004

-

State of the art review of the EcoBUDGET implementation in Tubigon, ICLEI, 2010.

-

Environmental Master Budget 2012, Republic of the Philippines, PROVINCE OF BOHOL, MUNICIPALITY OF TUBIGON, 2012.

-

Municipality of Tubigon. 2006. Powerpoint presentation on ecoBudget in Tubigon.

-

Province of Bohol. 2006. ecoBudge t Asia in Bohol Province: The Tubigon Municipality Case Study (An Environmental Management System). Powerpoint presentation.

-

Technical Interfaces between EcoBUDGET and PDMS, Dreams, 2009. Document interne.

-

Tubigon MPRAP Summary, December 2012.

Växjö

-

EcoBUDGET Guide for Asian Local Authorities, ICLEI, 2006.

-

EcoBUDGET: introduction for Mayors and Minicipal Councillors, 2007. Présentation powerpoint.

-

The EcoBUDGET guide: methods and procedures of an environmental management system for local authorities, ICLEI, 2004.