Learning more about climate change: a lever for reducing carbon footprints

Florian Fizaine, Guillaume Le Borgne, July 2025

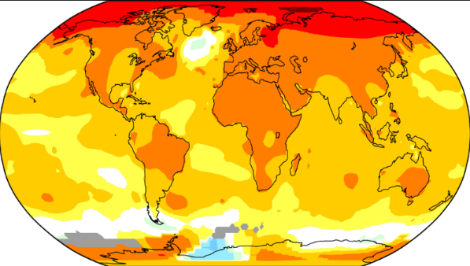

The more we know about climate change and the everyday actions that emit the most CO2, the smaller our carbon footprint. This is confirmed by a new study, which indicates that knowledge is an individual and collective lever that can reduce this footprint by one tonne of CO2 per person per year. But this will not be enough: the ecological transition must also involve public infrastructure and land use planning.

Successive reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), as well as the increasingly widespread coverage of the climate emergency by the media, show that information on the subject is now available to all. However, at the level of individuals, states and even intergovernmental agreements such as the COP, the effects of these reports seem very limited in view of the objectives set and the risks involved.

This observation raises questions about the role of accumulated and disseminated knowledge in the environmental transition. Rather than rejecting it outright, we need to revisit the forms it should take in order to enable action.

More knowledge to change behaviour: yes, but what kind?

Does more knowledge about global warming lead to change?

This is precisely the question we sought to answer in a recently published study. This work is based on a survey of 800 French people asked about their beliefs regarding global warming, their knowledge of the subject, and their behaviour and carbon footprint using the French Environment and Energy Management Agency (ADEME) simulator ‘Nos gestes climat’ (Our climate actions).

First of all, let’s clarify what we mean by knowledge. While our tool assesses knowledge related to the problem (the reality of global warming, its anthropogenic origins, etc.), a large part of our scale also assesses whether individuals know how to mitigate the problem through their daily choices – which areas of emissions, such as food or transport, and which actions have the greatest impact. Indeed, a good action requires not only identifying the problem, but also knowing how to deal with it effectively. And the French have very heterogeneous knowledge on this subject – a finding that is reflected at the international level.

The French have heterogeneous knowledge about the climate crisis

The researchers created a questionnaire on carbon impact by sector (transport, housing, food, etc.) to assess the French people’s knowledge of the climate crisis. Based on the percentage of correct answers and comparing this to the level self-assessed by the individual, we found that those who were most ignorant on the subject drastically overestimated their level of knowledge by more than a factor of two, while those who were most knowledgeable slightly underestimated their level by 20%.

When knowledge comes up against constraints

We have shown that the level of knowledge has a significant downward influence on the carbon footprint: on average, people with 1% more knowledge have a 0.2% lower carbon footprint. This can be explained by the multifactorial causes underlying the footprint.

We observe particularly different results depending on the carbon footprint category. Transport reacts strongly (-0.7% for a 1% increase in knowledge), food much less (-0.17%), while there is no observable effect on housing, digital technology and miscellaneous consumption.

These results are encouraging insofar as transport and food account for nearly half of the carbon footprint, according to Ademe.

The lack of results in other categories can be explained by various factors. In housing, for example, constraints are probably more significant and difficult to overcome than in other categories. It is easier to change vehicles than to change homes, and insulating a home is expensive and often associated with a very long return on investment. The occupancy status of the home (sole owner, co-owner, tenant, etc.) can also significantly hinder change.

Finally, with regard to the remaining items, it is likely that there is a combination of a lack of awareness of their impact, habits linked to social status and a lack of alternatives. Several studies have shown that individuals are very poor at assessing the impact of various types of consumption, and that the government guides intended for them provide little information on this subject.

As our questionnaire does not cover knowledge of all everyday choices, it is possible that individuals who are very knowledgeable about the impact of the largest items (housing, transport, food) and who scored well in our study would not necessarily have done so for other items (clothing, furniture, electronics, etc.). Furthermore, even if an individual knows that reducing their digital use or material consumption would have a positive effect, they may feel isolated or socially devalued if they change their behaviour.

Finally, digital technology is often perceived as non-substitutable, omnipresent and difficult for individuals to adapt. Unlike food or transport, it is difficult for individuals to perceive the carbon intensity of their digital uses (streaming, cloud, etc.) or to choose them based on this information.

Beyond individual knowledge: the role of public policy and social norms

Our study shows that up to approximately one tonne of CO2e/year/capita can be saved through a drastic increase in knowledge, which could be achieved through education, training, awareness-raising and the media. This is already good, but it is only a small part of the 6.2 tonnes of CO2e/inhabitant that needs to be avoided in order to reach the Paris Agreement target of 2 tonnes per inhabitant in France. This reinforces the idea that individual knowledge cannot achieve everything and that individuals themselves do not hold all the keys.

Individual actions depend in part on public infrastructure and regional planning. In this context, only decisions taken at different levels of government can remove certain constraints in the long term. On the other hand, politicians and businesses will not commit to measures that are disapproved of by a large part of the population. The triangle of inaction must therefore be broken in one way or another in order to bring the other two sides into play.

This is not to say that individuals are solely responsible for the situation, but rather to observe that through voting, consumption choices and behaviour, the levers and speed of change are probably greater on the part of individuals than on the part of businesses and governments.

How, then, can we mobilise citizens beyond improving their knowledge? We do not answer this question directly in our study, but there is a wealth of literature exploring two promising avenues.

The good news is that it is not always necessary to ban, subsidise heavily or impose restrictions to change behaviour. Sometimes, all it takes is to help people see that others are already taking action. Policies based on social norms – often referred to as nudges – capitalise on our tendency to align ourselves with what others do, especially in areas as collective as climate change.

With minimal public investment, we can therefore maximise the knock-on effects, so that change does not rely solely on individual goodwill, but becomes the new local norm. In Germany, for example, a recent study shows that when one of your neighbours starts recycling their bottles, you are more likely to do so too. This simple imitation effect, based on social norms, can create virtuous circles when combined with skilfully targeted public support measures or information.

Emotions, another individual and collective lever

Next, emotions – such as fear, hope, shame, pride, anger, etc. – each have specific behavioural functions which, when properly mobilised, can encourage the adoption of more environmentally virtuous behaviours. Researchers have proposed a functional framework linking each emotion to specific intervention contexts and demonstrated that this can effectively complement traditional cognitive or normative approaches.

For example, fear can motivate people to avoid immediate environmental risks if accompanied by messages about the effectiveness of the proposed actions (and, conversely, can paralyse them in the absence of such messages), while hope promotes commitment if individuals perceive a surmountable threat and their own ability to act. Furthermore, eco-anger can lead to stronger commitment to action than eco-anxiety.

Strategically targeting emotions according to audiences and objectives maximises the chances of behavioural change. Furthermore, mobilising emotions requires convincing individuals of the effectiveness of their actions (and the involvement of others) and of the surmountable nature of the climate change challenge. This is no small task, but it remains a central issue for research and those involved in the fight against climate change.

Sources

-

Florian Fizaine, Maître de conférences en sciences économiques, Université Savoie Mont Blanc

-

Guillaume Le Borgne Maître de conférences en sciences de gestion, Université Savoie Mont Blanc