PAP 67 : Landscaping and biodiversity, The example of the Bruche valley

Jean-Sébastien Laumond et Régis Ambroise, junio 2023

Le Collectif Paysages de l’Après-Pétrole (PAP)

With a view to ensuring the energy transition and, more generally, the transition of our societies towards sustainable development, 60 planning professionals have formed an association to promote the central role that landscape approaches can play in regional planning policies. Jean-Sébastien Laumond, land manager for the Communauté de communes de la vallée de la Bruche and founder member of the PAP collective, and Régis Ambroise, agricultural engineer and founder member of the PAP collective, present the actions and developments that have taken place in the Bruche valley since the first landscape plan was drawn up in 1991.

Para descargar: article-67-collectif-pap_jsl_ra.pdf (15 MiB)

To remedy a profound crisis in its economic and social model, the Bruche Valley was one of the first areas to adopt a landscape plan in 1991. Over time, this tool has fed into the evolution of its development practices, its landscape and the local culture of its inhabitants. The Bruche Valley was recently awarded the title of « French Capital of Biodiversity 2022 - Landscape and Biodiversity ». Awarded by the Ministry for Ecological Transition and the French Office for Biodiversity, this distinction highlights the impact on the local area of a programming and management tool, the landscape plan, whose recommendations have been implemented over the years by several waves of proactive policies.

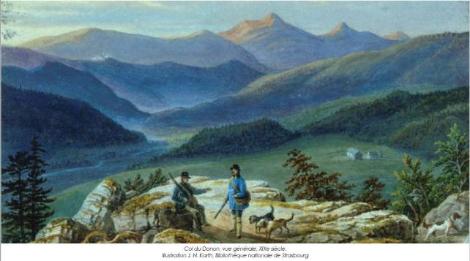

Situated in the north of the Vosges mountains, the Bruche valley was early identified by travel writers as a charming landscape with a marvellous combination of bare peaks, steep wooded slopes and villages set harmoniously amidst meadows and orchards 1. The valley was developed in the early 19th century by the construction of textile mills powered by water. In addition to forestry resources, which are often communal, the local economy has a significant agricultural component, with farm labourers securing additional income by meticulously developing the land around their villages. A typical form of mountain farming, the famous « combed Vosges » was created: gardens and potato plots on the outskirts of villages. Further out, terraced orchards and, above the forests on the slopes, summer pastures on the summits. In the 1970s, one factory after another closed. Often forced to work elsewhere, the inhabitants abandoned their country lifestyle and planted spruce trees to make their agricultural plots more profitable. The valley’s landscape has been transformed by the disappearance of the traditional activities of farm labourers, and by overgrowth and afforestation.

Landscape approaches at the heart of local development initiatives

Twenty years later, trees have grown everywhere. As in other regions affected by the decline of mid-mountain areas, elected representatives are taking steps to promote local development and make new use of the area’s resources and skills. The Bruche valley has developed an original approach, placing the landscape at the heart of its concerns in order to redefine agricultural uses and redevelop areas that have been damaged by years of neglect. Keen to improve the quality of life for local residents, the local councillors set their sights on the establishment of new craft and industrial activities and the development of green tourism, a concept that was being invented at the time. Launched in 1991, the landscape plan highlights the spatial organisation of the area, the links between the different landscape features and the potential resources of each zone. The first reopening works were carried out in the valley floor, which at the time was almost entirely obscured by conifer plantations, along the main road up the river Bruche, providing a showcase for the local authorities’ strategy.

The creation of a number of pastoral land associations has mobilised a large number of owners to structure the highly fragmented land. This pragmatic use of land has enabled farmers to increase the size of their holdings. This has led to a diversification of production, better-quality livestock and the development of direct sales and farmers’ markets. In addition, the farmers carry out work of collective interest, such as snow clearance and forestry work. The experience is considered positive by all the partners, who feel that the landscape approach has proved its worth. Spatial integration and the rise in quality of local produce have encouraged the virtuous circle described by Pierre Grandadam, Honorary President of the Bruche Valley Community of Communes: « We need to look after the people who look after the animals that give us beautiful meadows and good produce ».

Landscape approaches and biodiversity policies

Policies to promote biodiversity have been developed at national and European level since the 2000s: for farmers, agri-environmental measures (MAE) and, at regional level, the network of green and blue corridors linking the Natura 2000 areas with the greatest biodiversity. These areas are often found in the depths of forests with little artificial development.

Landscape and biodiversity in the meadows

Travellers marvelled at the colour of the flowers, the smell of the grass and the diversity of the components of these Bruche landscapes. A major awareness-raising campaign was then launched with farmers to draw up specifications tailored to the specific features of each landscape unit. The first agri-environmental measures - territorial agri-environmental measures, then climatic measures: MAET and MAEC - were introduced in 2007, with the Community of Communes taking the lead. In a second wave of measures in 2012, the local authority included obligations to achieve results ("flowering meadow" measure with the notion of indicator plants on the plots) and obligations to provide means (delayed mowing, no fertilisation, etc.). This programme makes an effective contribution to preserving grassland biodiversity 2. It has succeeded in convincing all those involved - elected representatives, AFP owners, local residents, etc. - that the farming activity practised in the Bruche is indeed the key.

With around forty people taking part each time, several days of field visits were organised to teach everyone how to identify grassland species. By demonstrating the richness of grasslands and their importance in farmers’ production systems, it is becoming clear to everyone that natural grasslands are not intended to be used as building plots, but that, in town planning documents, elected representatives must protect them for their landscape, agricultural and biodiversity functions.

In this way, the landscape plan is demonstrating its effectiveness not only in terms of the living environment, but also in establishing that the work of farmers is capable of enhancing the quality and functionality of environments and promoting the diversity of species. This work, entitled « Vision paysagée, Vision partagée », took place over two years, between 2011 and 2012, and was punctuated by a public event, « Festi’val du paysage », involving more than thirty partners on the site of four farms.

Since 2014, farmers have taken part every two years in the national competition for flowering meadows (now known as the competition for agro-ecological practices - meadows and rangelands). One farm will win a prize at the general competition in Paris in 2021. The competition for flower meadows assesses their floristic, forage and melliferous qualities. In the Bruche Valley, two new dimensions will be added: an expert on the panel of judges will analyse the way in which the meadow contributes to the quality of the landscape in which people live, while a top chef will reveal the gastronomic value of the species that grow there.

To further our understanding of grassland biodiversity, studies and initiatives have been undertaken to analyse how the spatial characteristics of plots can contribute to this richness, and to identify the development and maintenance principles that can be implemented to enhance it. Maintaining exchanges between the grazed stubble on the summits, the sloping hillsides according to their orientation and the wet valley bottoms encourages a wide biological variety in the plots. This eco-landscape approach provides farmers and elected representatives with food for thought as they plan the sustainable landscapes of tomorrow.

The role of rural trees

As part of the drive to return to grass some of the plots planted with conifers at the end of the twentieth century, more detailed work is gradually leading to an interest in the contribution of country trees to these landscapes and their biodiversity. A group of orchard enthusiasts got together in 1997 to organise the development of fruit trees. The installation of a collective wine press was a great success with the valley’s owners, as were the training courses on tree pruning, grafting techniques and choosing plants suited to the diversity of the environment. By taking pleasure in caring for their trees, each member of the pressoir improves their living environment and the landscape of the valley, while helping to enrich the area’s biodiversity.

This process, which has been under way for over thirty years by the association of family harvesters, forms the backdrop to an interest shared by all the partners in rethinking the role of country trees in agricultural environments. In the context of global warming, the thinking behind agroforestry takes into account livestock systems, fodder resources and, above all, the enhancement of biodiversity.

Today, on the perimeters of existing or planned AFPs, attention is paid to the choice of tree structures (high or low hedges, isolated trees, alignments, copses, etc.) that will be preserved and/or planted, and to their location in relation to the relief, the water system and the borders around the plot, as well as the use that farmers will make of them. The aim is also to be able to provide shade for the animals and fodder in times of drought thanks to the leaves of the trees. Through the choice of hedgerows and trees planted in rows and, more generally, the aim of restoring light to the valley, landscape quality remains a permanent objective of these actions.

Landscape and biodiversity for local residents

The valley’s residents live in their daily landscapes, using them in a way that is linked to a contemporary culture of cleanliness and simple maintenance. The communauté de communes has developed a genuine communication strategy to raise public awareness of the landscape initiatives undertaken by the local authority and to explain their objectives. By recounting the history of the valley’s landscapes and disseminating knowledge about the environment, local residents can regain an understanding of their surroundings: grassland is not just a green carpet, the plants present are important indicators, copses, hedges, isolated trees and low walls all play a role, and the presence of animals is essential. With this in mind, viewpoints equipped with interpretation tools have been set up across the region to showcase these landscapes and explain all their components.

Very early on, the Vallée de la Bruche Community of Communes introduced a « green and blue network » approach aimed at preserving species and their habitats on a regional and national scale. A study analysing the relationship between the quality of landscapes, the agronomic quality of environments and the functionality of ecosystems throughout the valley was approved in December 2022. An environmental diagnosis has been carried out on all twenty-six communes, justifying the continuation of a dynamic of actions that increasingly integrate the issues of landscape perception and the agro-eco-systems on which they are based. The landscape approach has described the spatial organisation of the area and enabled us to understand its « matrix », on the basis of which we can carry out work to improve its green and blue webs.

Demonstration through action

The pastoral renovation work carried out in four communes covering more than 80 hectares at the bottom of the Bruche valley illustrates the link between reopening up the landscape, pastoral land associations and biodiversity. Under the management of three AFPs, this project, which began in 1996, has been carried out in several phases, the last of which is currently nearing completion. Its aims are to clear and maintain the area along the river to open up new spaces that will support farming activity. In order to restore the land, work began by clearing the wooded areas on the 75% of the plots that were forested. These wooded or fallow areas are being returned to grassland by mechanically levelling the softwood stumps and maintaining islands of trees and shrubs to create a mosaic of environments with multiple uses (refuge for game, small fauna, birdlife, plant biodiversity) while respecting the riparian environments along the Bruche. Access to the area and its pastoral management are facilitated by access roads and superficial hydraulic works. Fencing surrounds the grazing areas. The quality of the landscape is remarkable: a corridor of greenery at the bottom of the valley, an open landscape regained, made up of permanent grassland with a view of the major bed of the Bruche and its tributaries. This series of viewpoints is a real showcase for the Bruche Valley, flanked on both sides by the main road and the railway line that run up the valley.

Landscape approaches linked to new themes

The mobilisation of local audiences around biodiversity and landscape issues currently concerns both urban planning and forestry stakeholders, while the growing awareness of global warming is sparking a debate that is gaining momentum with each passing day.

Landscape and town planning

The first landscape plan highlighted the importance of brownfield sites in villages. At one time considered to be landscape warts to be erased or forgotten, they now represent a heritage that makes it possible to implement a long-term land policy. The valley’s new-found quality of landscape is attracting new populations looking for building land. These derelict sites offer plenty of space to build on without having to cut back on the agricultural land around the villages. In some cases, there are plans to develop recreational areas with a strong emphasis on nature. The interest shown in biodiversity in agricultural areas over the last few years is now widely accepted. Many elected representatives are committing their departments to a ‘zero pesticide’ policy in the management of cemeteries and public gardens. In addition, it has now been established that agricultural land adjoining villages, and often grouped together in AFPs, cannot be used for building, thereby counteracting the general trend towards urban sprawl, which is just as fatal to biodiversity as it is to the landscape.

Landscape, biodiversity and forests Occupying more than 77% of the territory, forests had remained on the fringes of public development policies. Today, relations between private owners, the ONF and elected representatives are being strengthened as new challenges emerge. Many plots of spruce are drying out, victims of bark beetle attacks and the summer droughts of recent years. The models implemented in the second half of the 20th century, by both the ONF and private owners, are now being called into question. An increasing number of professional leaders are promoting the evolution of monoculture forestry systems towards more diversified systems, according to each type of plot, leaving more room for biodiversity. By developing regular exchanges in the field between foresters, hunters, elected representatives, schoolchildren and hikers, the various players are striving to find landscape approaches that reinforce the multifunctional role of the forest, in particular as an energy resource. These objectives were the theme of the first edition of the « Printemps de la forêt », organised on 21 and 22 May 2022 in conjunction with all these stakeholders, to raise public awareness of these environmental, social and economic issues.

Landscape, biodiversity and adapting to global warming

Many problems remain to be tackled. Invasive species are developing along rivers, in meadows and sometimes in allotments; the proliferation of roe deer, wild boar and, more recently, wolves is causing damage and harm to certain sections of the population. The ambition of low-carbon mobility also remains difficult to achieve, although the train has been maintained in the valley. However, the urgency and intensity of global warming call for a change in working methods. If we abandon the use of chemical fertilisers, which have contributed to climate change, new « climate-soil-plant » balances adapted to each area will emerge. Allowing natural selection to unfold will undoubtedly lead to adaptations, but we need to think about the introduction of new species: how can landscapes be developed to best ensure these transitions? How can the landscape approach help local players to implement a forest strategy for the Bruche valley?

A sustainable development policy based on controlled land management

The local development process introduced in the Bruche valley was originally based on a landscape plan, from which a variety of intervention themes were developed. A detailed analysis of the area’s historical and geographical features has enabled us to identify the forms and consequences of recent and less recent developments. Based on the observation of a demographic and economic crisis, a large

A wide range of stakeholders were mobilised in the local population: owners within the AFP, farmers concerned with the meadows, owners of the fruit trees, elected representatives responsible for the public good, teachers and their pupils, associations. This mobilisation was the basis for multifunctional, spatialised development projects rooted in the area. Accepted and shared by the local population, their quality is recognised by locals and visitors alike. The Bruche Valley landscape plan is therefore conceived as a social project. Its implementation calls for awareness-raising and animation in order to involve local professionals as well as the general public of inhabitants and visitors. To this end, the intermunicipality has had a full-time project manager from the outset, whose main task is to ensure an operational presence on the ground in contact with everyone. Combining an overall strategic vision with constant pragmatism, his role is to promote and disseminate best practice to ensure that the landscape evolves towards greater coherence, functionality and amenity in terms of agronomic efficiency, biological diversity and social uses.

From the outset, for local players, landscape policy has not been conceived as the protection of the great landscape, but as the redevelopment of degraded living spaces. A new landscape based on a balance between the natural capacities of the environment and the fundamental needs of the population would restore pleasure, confidence and pride to the inhabitants. The creation of new activities helped to develop a sense of belonging among the local population. In this way, the rehabilitated and requalified landscape has once again become the project of an entire valley, proclaiming « Welcome is in our nature » and proposing its landscape as the living embodiment of a social and environmental pact capable of ensuring the sustainability of the earth’s environment.

-

1 « The Bruche valley has been a subject of landscape design since the 19th century. Today it is an entry in the pages of tourist guides devoted to the Vosges Moyennes. It is recognised as a landscape, but above all as a place of history, particularly industrial history and the memory of the Holocaust. (…) The Bruche valley and its villages attracted the attention of 19th century painters and illustrators. Most of the market towns were depicted nestling at the bottom of the valley, with its wooded slopes and mountainous horizons creating a picturesque and harmonious setting ». Atlas des paysages d’Alsace, Représentations et images des Vosges Moyennes www.paysages.alsace.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/spip.php?article134

-

2 Monitoring has been carried out in partnership with INRAE-ENSAIA in Nancy, showing that these mid-mountain meadows, whether or not they have been planted with spruce, have a wide variety of flora, due in particular to the diversity of geographical situations, relief, the absence of chemical fertilisers and, of course, farming practices.