Park dweller’s fight in Osaka, Japan

Homeless people demanding the right to the city

Marie BAILLOUX, 2009

Background and context

Foreigners believe that Japan has no urban slums, but modern capitalism depends ultimately on the exploitation of the poor people, who live and work in awful conditions.

Four years ago, a Japanese government survey discovered that Japan had 25,296 homeless people, living in city parks, along riverbanks, near train stations, in internet cafés, and on other public land, from which more than 40% lived in parks. Osaka’s prefecture has the largest homeless population in Japan – 7,700 by official figures, and more than 15,000 unofficially. Since the 1990s, there has been a great shift towards park-dwelling, as the economic crisis triggered a rapid increase in unemployment figures. Recession and unemployment are the single greatest causes of homelessness.

When socially-vulnerable unsheltered people collectivize and create safe communities in public parks, it represents a factor of protection for their physical and mental health, and a greater capacity to organize their survival skills and civil resistance. But the authorities violently evict tents and their rough sleepers, remove and destroy their personal belongings so as to “cleanse” parks of homeless people and “have nice public spaces”, forcing them to try to survive on the streets. As they spread, the risk of their destruction also increases. Following the words of the Governor “… (because of the homeless) young girls are no longer able to do gymnastic training or any exercises in the parks in the afternoons”: poor people are victims of physical violence but also of prejudices and deep social exclusion.

Furthermore, a citizen without a registered address is excluded from many other rights, including the right to vote, join the national health insurance system, and obtain a driver’s license or passport. Day laborers chronically out of work cannot receive unemployment benefits; nor can they apply for welfare assistance, which requires recipients to maintain a permanent address. Social welfare administrations are not providing Japanese citizens even the minimal level of subsistence as guaranteed in the Constitution. Once one becomes homeless, not having an address makes it barely possible to find work, therefore, to ensure his livelihood to have a place to live.

Networks and Alliances specific perspective

Since the 1990s, as the Asian economy went downhill leading to a rapid increase in street-sleepers, some 30 such organizations joined to launch a national network to help people on the street to formulate their grievances and become more self-reliant.

For labor activists and other activists, the homeless should not be treated as wards in need of protection, but are encouraged to build healthy social relationships inside their own communities and fight against social exclusion. At the same time, they need to learn to struggle in an organized way for their right to a decent existence and against human rights abuses. They struggle for the right to decent shelter but also for the right to not be evicted.

Mr. Yoji Yamauchi’s resistance

Since 1998, Yoji Yamauchi, a 58- year-old Japanese, is homeless. His shelter is a blue removable lightweight tarpaulin tent in a park in the industrial city of Osaka.

He has started up a singular struggle to fight against the gross violation of Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, to which Japan is a signatory (“…the right of everyone to… housing”) in alliance with homeless people’s associations against the authorities, to fight against forced eviction and be recognized as homeless with right to the city through having an official address in the street.

In June 2001, sponsored by the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, he was part of a homeless groups and support people delegation who visited Hong Kong to evaluate the conditions of life of local homeless people and exchange experiences.

In March 2004, the Kita Ward (Tokyo North local entities directly controlled by the municipal government) refused to register the park as his address.

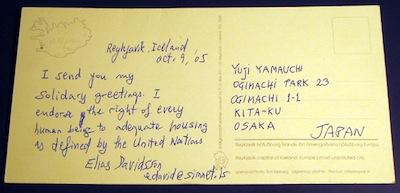

In April 2005, an international solidarity campaign led by “Koen-no-Kai” (The Park Collective) of sending post-cards to Mr. Yamauchi’s “illegal” postal address in the Ogimachi Park as a lobbying campaign to have it validated by the authorities, was supported by Habitat International Coalition (HIC).

Decided to have his human right to housing recognized, he filed a lawsuit with the Osaka District Court and won the case in January 2007, as the district court backed his claim ruling a person’s residence is the place where that person lives, regardless of whether one has the right to live at the location.

The City Office appealed against the original ruling, arguing that a tent is not a permanent structure and sent the case to Osaka High Court, which overturned the ruling in 2007. It declared that it was illegal to use a park as an address, arguing that the tent, being removable, does not meet the standards of a residence by ‘conventional wisdom’ and adding that the approval of the previous verdict would encourage other people to move into the park.

Mr. Yamauchi and his lawyer then appealed to the Supreme Court.

In October 2008, after a year and a half silence, the Supreme Court dismissed the case. This case finished without true resolution.

Japan -just as other “developed” capitalist societies- has its share of urban slums, where marginalized groups congregate in search of work and a decent place to live. In a modern capitalist country, with a capitalistic model of production and organization, unsheltered people are not even authorized to sleep in a removable tent in the street and are systematically victims of evictions.

The right to the city includes the full benefit for all citizens of the use of public spaces and access to income-generating opportunities, land and housing, water and sanitation, education and health care. Following the Principles and Strategic Foundations of the “World Charter for the Right to the City”, it also involves: full exercise of citizenship, democratic management of the city, socially-friendly city and urban property, equality and absence of discrimination, special protection for vulnerable groups and individuals, social commitment of the private sector, promotion of the solidarity economy and progressive taxation policies. None of these aspects of the right to the city has been recognized or respected in the case presented here.

Since 2005, Habitat International Coalition has supported various calls to solidarity actions to help Japanese homeless people and to help preventing forced evictions. Of these various advocacy initiatives for the right to the city, the most persistent actor has always been Mr. Yoji Yamauchi. He has been demonstrating a long-term commitment to the struggle as well as amazing skills to form bonds and attract gestures of solidarity from all over the world.

The “Postcards campaign” launched in 2005 was pragmatic, simple and had a good impact. Its success depended on popular participation, and managed to raise international awareness about the pathetic conditions of Japan homeless in 2005-2006. It eventually contributed to Mr. Yamauchi winning his case with the Osaka District Court in early 2007, and gave him hope and energy to keep on fighting to break out of this vicious circle.