Removing the Speculative Nerve from the Right to Property

Marc UHRY, 2014

This article is part of the book Take Back the Land ! The Social Function of Land and Housing, Resistance and Alternatives, Passerelle, Ritimo/Aitec/Citego, March 2014.

A Social and Economic Must

Economists with different viewpoints agree on at least one point: the excessive return of private income compared to productive investment is choking our societies’ economies.

This is especially true when it comes to housing. The current crisis has been characterised by an unprecedented hike in land prices over the last fifteen years, which has resulted in three problematic impacts: 1) investors’ resources have been eaten up by this price increase rather than by building, which has exacerbated the shortage. 2) The user costs of housing have skyrocketed well beyond households’ means. 3) There are numerous and overlapping public policies to keep private capital on the real estate market. Public authorities are thus contributing to inflating prices, which in turn require new public initiatives to ensure return on investment… This has been feeding into a speculative bubble, which eventually bursts with a “crash landing”: a drop in prices brutal enough to severely damage the production apparatus and its numerous jobs, as has been demonstrated in several European countries.

The issue at hand is squaring the following circle: how can housing be made less expensive for users but equally attractive for investors?

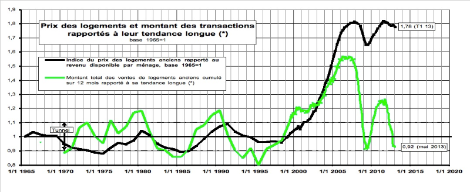

The traditional solutions to this dilemma are ideologically polarised, which does not contribute to making headway: on the one hand, liberals believe that if private initiative is unbridled thanks to return on investment, production will increase and eventually meet social needs, which will in turn make prices decrease. Alas, this solution has prevailed for the last thirty-five years and the market has failed to reach self-regulation. The financialisation of the real estate market has set off a growing divide between the housing ownership market and the housing users’ market. Prices are constantly running out of control and periodically construction becomes sluggish, even though the existing stock is sufficient to solve the shortage problem. Over the last decade, an unprecedented gap has grown between housing prices and households’ income, in which market elasticity no longer relies on price trends but rather on sales volumes, as illustrated in this chart: as soon as prices seem to stabilise, even at an extremely high level, sales drop and production slows down.

On the other hand, advocates of market regulation overlook its discouraging impact on investment, in a context where private players - including households - account for over 80% of new production. Markets have not been regulated for a long time now and demonstrating this hypothesis is problematic, but it is a deeply rooted belief among private housing players.

This observation has led to new initiatives around the world which seek to combine individual freedom and general interest. The unsolvable dilemma is no longer being debated by advocates and opponents of private property - rather, it is being played out through more fruitful experiments which strike new balances between users and ground rent. These initiatives are carried out within the very framework of the right to property and are impelled by the evolution of international law.

International Law: Ownership versus Ground Rent?

In June 2013, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) dismissed a request made by Dutch landlords who were attacking rent regulations in their country1, on the grounds of Article 1 of Protocol 1 to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms: « Every natural or legal person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions. No one shall be deprived of his possessions except in the public interest and subject to the conditions provided for by law and by the general principles of international law. The preceding provisions shall not, however, in any way impair the right of a State to enforce such laws as it deems necessary to control the use of property in accordance with the general interest or to secure the payment of taxes or other contributions or penalties. »

The Dutch landlords had not caught on to the idea that the right to property is sacred, but only within the boundaries defined by public authority. French law also sets out similar boundaries, with the following definition: “Property is the right to enjoy and have things in the most absolute manner, provided that one does not make of it a use prohibited by the laws or regulations » (article 554 of the Civil Code). In French law, as in international law, the right to property is limited by general interest. As a matter of fact, urban planning regulations prohibit building anything on land one owns; a landlord cannot let substandard housing; the tax on vacant housing penalises a specific use, etc. Property is an “artichoke-like right” 2, since its layers can be peeled off without altering its nature, as long as its core is not damaged.

Beyond this agreement on the law’s faculty to limit the freedoms granted by the right to property, there is a substantive difference. In our Roman law country, property is linked to the deed, which is an exclusive legal bond between a person and an object. In English, the other official language of the EHRC, the right to property takes on a quite different meaning. Property based on a deed is called ownership. But the Treaty uses the term property, which refers to John Locke’s philosophy and defines property as what is proper to the individual. The French version of the treaty “…personne a droit au respect de ses biens…” is not an exact equivalent of the English version, in which the idea of possessions goes beyond the idea of “goods” (which is a more accurate translation in English of “biens”).

This concerns the very nature of what is protected by the right of property: the EHRC defines possession as having a “substantial interest”, since its layers can be peeled off without altering its nature, as long as its core is not damaged.

Beyond this agreement on the law’s faculty to limit the freedoms granted by the right to property, there is a substantive difference. In our Roman law country, property is linked to the deed, which is an exclusive legal bond between a person and an object. In English, the other official language of the EHRC, the right to property takes on a quite different meaning. Property based on a deed is called ownership. But the Treaty uses the term property, which refers to John Locke’s philosophy and defines property as what is proper to the individual. The French version of the treaty “…personne a droit au respect de ses biens…” is not an exact equivalent of the English version, in which the idea of possessions goes beyond the idea of “goods” (which is a more accurate translation in English of “biens”).

This concerns the very nature of what is protected by the right of property: the EHRC defines possession as having a “substantial interest”3. Administrative authorisations, ranging from the right to remove gravel4 to fishing permits5 and drivers’ licenses, are included in this definition of possessions6. There is an important element, however, regarding housing: the Court acknowledges the rights entailed by being a tenant7. as a possession. The right of property consists in having a substantial interest in something. A legitimate hope can be viewed as a substantial interest and thus becomes a possession protected by the right to property. Not renewing a lease has been considered as an infringement on the right to property8, just as a non-fulfilled expectation of a service accommodation, guaranteed by internal law9.

This definition of property, focused on use, opens legitimate fields for public policy. In Mellacher v. Austria (1989), the Court determined it would “hardly be consistent with these aims nor would it be practicable to make the reductions of rent dependent on the specific situation of each tenant. […] It is undoubtedly true that the rent reductions are striking in their amount [22 to 80%]. But it does not follow that these reductions constitute a disproportionate burden. The fact that the original rents were agreed upon and corresponded to the then prevailing market conditions does not mean that the legislature could not reasonably decide as a matter of policy that they were unacceptable from the point of view of social justice”. Beyond rent regulation, this also applies to the extension of valid leases or to the adjournment of eviction orders (Immobiliare Saffi v. Italy, 1999). In its Marckx v. Belgium decision (1979), the Court specifies the relationship between possessions and property: “(…) By recognising that everyone has the right to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions, Article 1 (P1-1) is in substance guaranteeing the right of property. This is the clear impression left by the words « possessions » and « use of property » (in French: « biens », « propriété », « usage des biens »); the « travaux préparatoires », for their part, confirm this unequivocally: the drafters continually spoke of « right of property » or « right to property » to describe the subject-matter of the successive drafts which were the forerunners of the present Article 1 (P1-1). ». Consequently, the Court has considered that the notion of property can be used to defend inhabitants in illegal slums (Oneryildiz v. Turkey, 2002): “ The Court reiterates that the concept of “possessions” in the first part of Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 has an autonomous meaning which is not limited to ownership of physical goods and is independent from the formal classification in domestic law ».

The European Human Rights Court has pressed for amending the French definition of the right of property, in favour of user property. International law and its definition of the right of property are absolutely not an obstacle to voiding it of its speculative nature, on the contrary.

« Let a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend! »

The remaining issue is the cultural and political acceptation of a redefined right to property, after a twenty-year consensus which ensued from the fall of the Soviet Union. « It doesn’t matter whether it’s a white cat or a black, I think : a cat that catches mice is a good cat », stated Deng Xiaoping on the dawn of this era of consensus.

Quickly, the imbalances caused by this evolution have made it necessary to call into question, once again, the relationship between individual freedom and collective wellbeing. The most significant element in this process was the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, awarded to Elinor Ostrom and Oliver Williamson for their research on the “commons”. The Nobel Academy established the idea of reaching a new balance between individual and collective interest, within the right to property, as a new paradigm in economic theory. This confirms a myriad of initiatives, all over the world: inhabitants’ cooperatives in Germany, community work and living units in Catalonia, popular investment funds, slum renovation cooperatives, popular urban planning initiatives in Sri Lanka…

These initiatives also exist in France and in the housing sector, and they are reshaping the right to property. Several initiatives have received support from local authorities and aim at developing non-speculative mutual benefit initiatives: in the Ile-de-France region (the Paris area) and in Lyon, players have been considering adopting the American Community Land Trusts (which have already been imported in the UK and in Belgium). These Land Trusts distinguish between land ownership and property of the walls, allowing for a cheaper access to land use in exchange for giving up ground income. In Alsace, fair self-promoting neighbourhoods are being encouraged. Social landlords sell homes to their inhabitants, with non-speculative clauses. Inhabitants’ cooperatives are thriving, with diverse legal forms and statutes. These collaborative projects are redefining the functions of habitat and creating a neighbourhood-based form of democracy. Ground rent is no longer an obvious component of the right to property. This novel situation is an opportunity to live differently, to gain ownership over other elements of habitat: its design, occupation statutes, the definition of user costs, its relationships with the surrounding environment. This change is an opportunity to replace competition-based relationships with cooperation-based relationships. Individuals, organisations and local authorities are now experimenting with it. Regulating land uses, types of construction, financial engineering, collective and individual legal statute… France, Europe and the world are planting the seeds of sustainable development within the chipped vault of an all-consuming individual property.

The ground rent society is overheating and self-management experiments, as well as systemic transformations based on firmly grounded theoretical constructions, are currently coming together to overthrow an obsolete form of organisation.

1 Nobel c/ Pays-Bas, 27126/11.

2 This expression was used by François Luchaire, a member of the Constitutional Council, in a memo to the Council on the right to property.

3 The Court considered that the idea of respect for possessions means right to property. EHRC, 1979, Marckx v Belgium.

4 EHRC, 1991, Fredin v Sweden.

5 EHCR, 1989, Baner v Sweden.

6 EHCR, 1992, Pine Valley Developments v Ireland.

7 EHCR, 1990, Mellacher v Austria.

8 EHCR, 2002, Stretch v United Kingdom.

9 EHCR, Shevchenko v Russia (2008), Burdov v Russia (2004), Novikov v Russia (2008) Nagovitsine v Russia (2008), Ponomarenko v Russia (2007), Sypchenko v Russia (2007), etc.